The Rise of Macedon

The story of the Hellenistic world begins not with a slow evolution but with a series of seismic shifts initiated by the Kingdom of Macedon under the leadership of Philip II. Ascending to the throne in 359 BCE, Philip II inherited a kingdom on the fringes of the Greek world, beset by internal strife and external threats. Yet, through a combination of military innovation, diplomatic manoeuvring, and sheer will, Philip transformed Macedon into the preeminent power in Greece.

Philip’s reign was marked by a series of military reforms that would revolutionize Macedonian warfare and influence the course of European military history. The most notable of these was the development of the Macedonian phalanx, a tightly organized infantry formation that utilized long pikes (sarissas) to devastating effect. This innovation, combined with the use of cavalry for flanking manoeuvres, made the Macedonian army nearly invincible on the battlefield.

Diplomacy, however, was equally instrumental in Philip’s rise. Through strategic marriages, alliances, and the judicious use of force, he expanded Macedonian influence over the Greek city-states, often preferring to integrate rather than annihilate. The culmination of Philip’s campaign in Greece was the Battle of Chaeronea in 338 BCE, where the combined forces of Athens and Thebes were decisively defeated, leaving all of Greece, save for Sparta, under Macedonian hegemony.

The establishment of the League of Corinth in 337 BCE marked the zenith of Philip’s power, uniting the Greek city-states under Macedonian leadership against their common enemy, Persia. This alliance, however, was not merely a military pact but also a reflection of Philip’s broader vision for a united Hellenic world, a vision that would be inherited and expanded by his son, Alexander.

In 336 BCE, the accession of Alexander the Great to the throne of Macedon signalled the beginning of a new era. Alexander, educated by Aristotle and imbued with a Pan-Hellenic vision, would go on to extend the boundaries of the Hellenic world to the farthest reaches of the known world. However, it was Philip’s foundational reforms and diplomatic acumen that laid the groundwork for his son’s unprecedented conquests. The Rise of Macedon under Philip II thus set the stage for the Hellenistic age, an era defined by the diffusion of Greek culture across a vast empire forged by the sword and shaped by the vision of its Macedonian architects.

Alexander the Great: Conqueror of Asia and India

Alexander the Great, inheriting the expansive ambitions and unparalleled military apparatus of his father, Philip II, embarked on a campaign of conquest that would forever etch his name into the annals of history. His ascension to the throne in 336 BCE marked the beginning of an era characterized by unprecedented military campaigns that extended the Hellenic world from the Balkans to the Indus Valley.

Conquest of Asia

Alexander’s conquest began with the bold decision to continue his father’s unfinished mission: the invasion of the Persian Empire. In 334 BCE, he crossed the Hellespont into Asia Minor, marking the start of a series of battles that would see the downfall of the Achaemenid Empire. The Battle of Issus in 333 BCE and the Siege of Tyre in 332 BCE were pivotal victories that demonstrated Alexander’s tactical genius and the might of the Macedonian army. His strategy of rapid, decisive engagements, coupled with his ability to adapt to the varied terrains of Asia, underscored his military prowess.

Governance and Tactics

Alexander’s governance strategy was as innovative as his military tactics. He adopted a policy of fusion between Macedonian and local cultures, encouraging marriages between his soldiers and native women, and integrating Persian satraps into his administration. This approach not only secured the loyalty of conquered territories but also facilitated the spread of Greek culture across his empire.

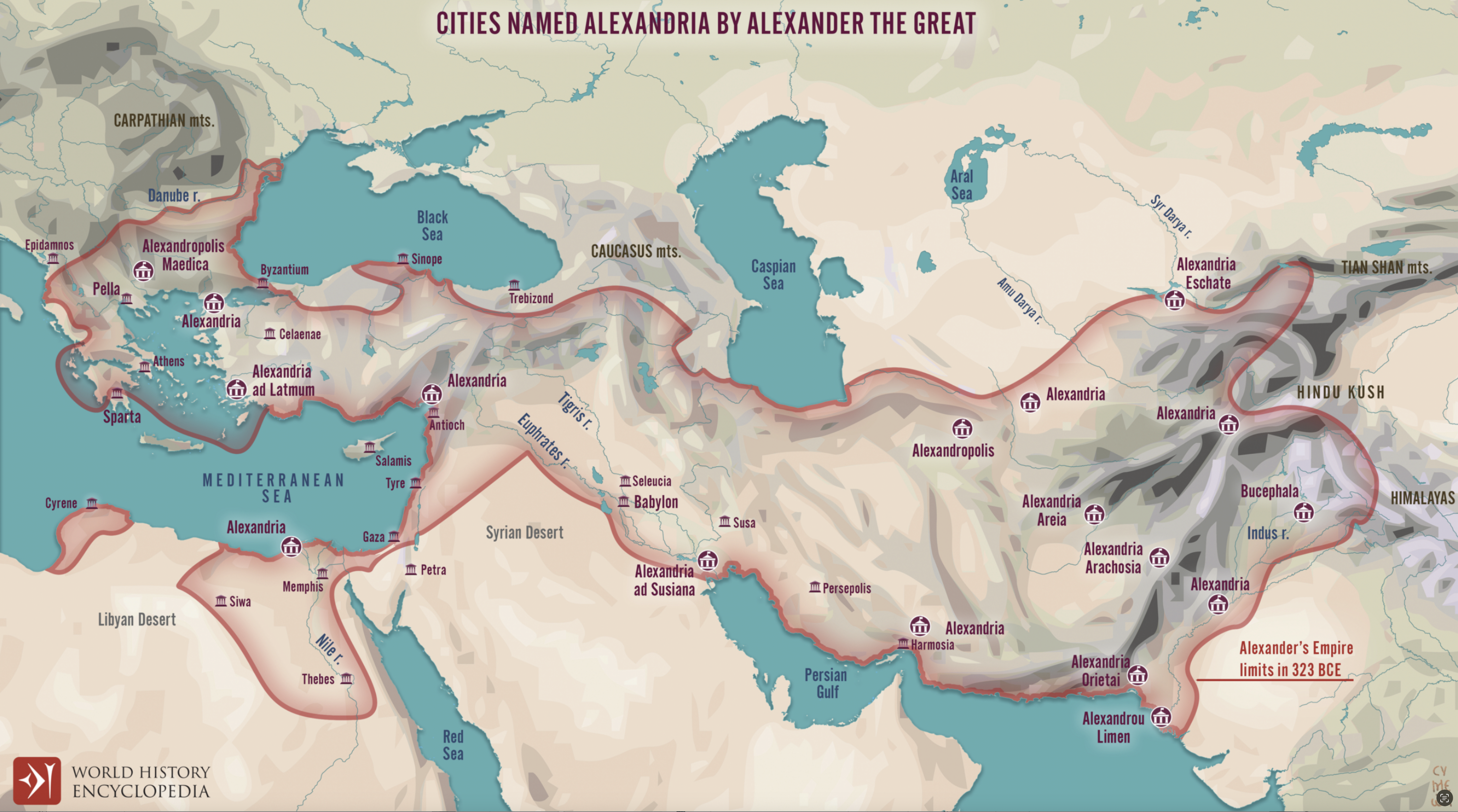

Establishment of New Cities

The foundation of new cities was another cornerstone of Alexander’s strategy for consolidating his empire. Perhaps the most famous of these was Alexandria in Egypt, destined to become a beacon of Hellenistic culture, science, and commerce. These cities served not only as administrative centres but also as focal points for the diffusion of Greek culture and the promotion of trade and knowledge exchange across the vast empire.

Journey to India and Death

Alexander’s insatiable appetite for conquest led him to India, where he achieved significant victories, including the Battle of the Hydaspes in 326 BCE. However, the gruelling campaign took a toll on his men, who, weary and longing for home, persuaded Alexander to return. The journey back was marked by hardship and loss, reflecting the human cost of Alexander’s ambitions.

In 323 BCE, Alexander the Great’s journey ended abruptly in Babylon. His death, at the age of 32, left a power vacuum that would lead to the fragmentation of his empire among his generals, the Diadochi. Yet, Alexander’s legacy was indelible. He had not only created an empire that spanned three continents but also laid the groundwork for the Hellenistic era, characterized by the spread of Greek culture and the blending of eastern and western civilizations.

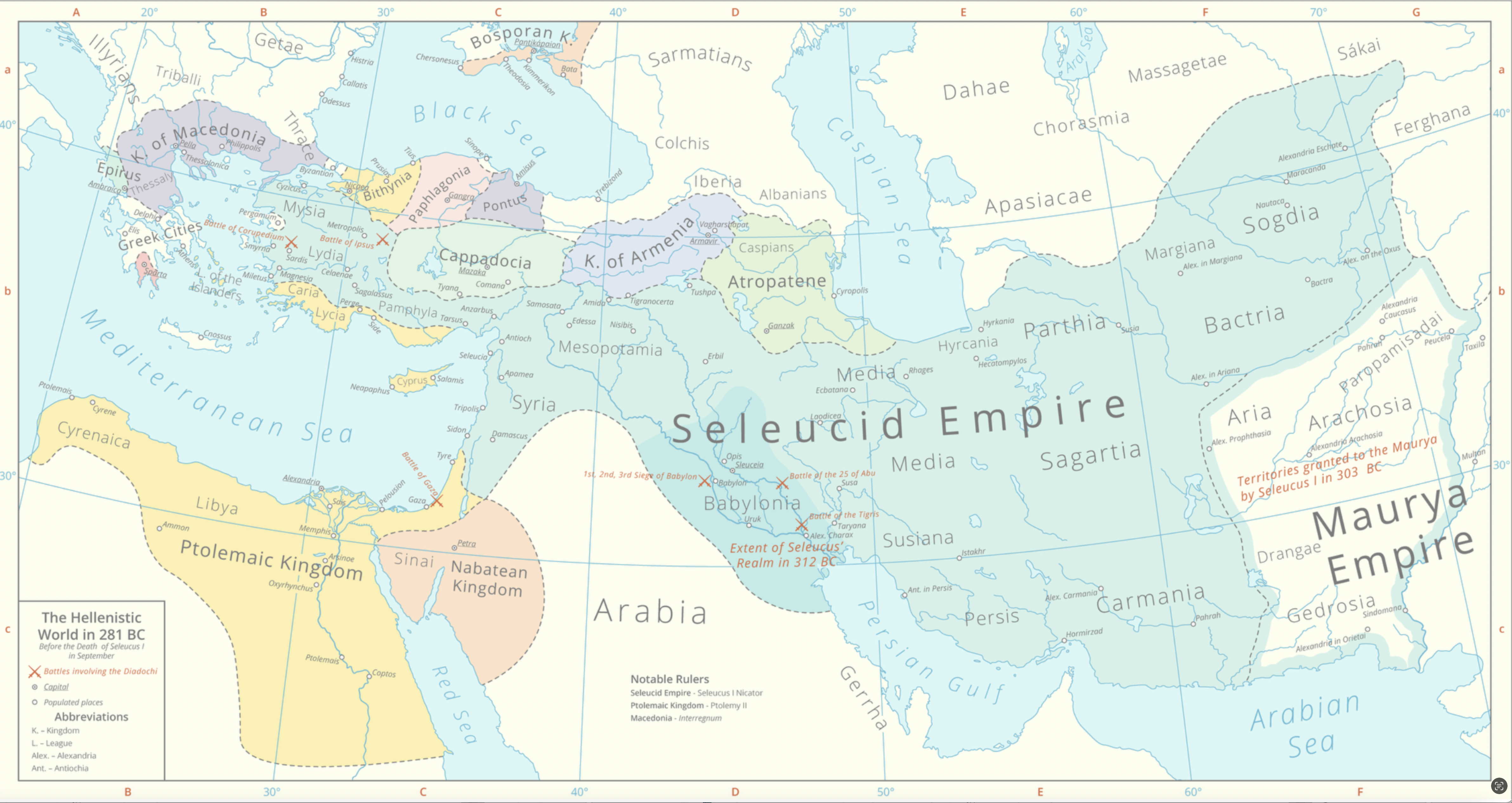

The Dawn of the Hellenistic Kingdoms: From Division to Stability

The sudden death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE plunged his vast empire into a period of uncertainty and turmoil. The absence of a clear successor led to the fragmentation of the empire among his generals, known as the Diadochi, sparking a series of conflicts known as the Wars of the Diadochi. These tumultuous years were marked by shifting alliances, betrayals, and relentless battles for supremacy. However, from this chaotic crucible emerged a new order, characterized by the formation of three major Hellenistic kingdoms that would dominate the ancient world: Macedon, the Seleucid Kingdom, and Egypt under the Ptolemies.

Macedon and the Greek City-States

In the aftermath of Alexander’s death, Macedon, the heartland of his empire, struggled to maintain its prominence in the face of internal strife and external pressures. The kingdom experienced a series of power struggles, but eventually found a semblance of stability under the Antigonid dynasty. This period saw Macedon retaining its influence over the Greek city-states, albeit amidst the backdrop of continuous power jockeying among the Hellenistic monarchies. The Antigonid rulers focused on fortifying their control over Greece, leading to conflicts with other Hellenistic realms and the emerging power of Rome.

The Seleucid Empire and the Mauryan Exchange

One of the most intriguing episodes in the early Hellenistic period was Seleucus I’s ceding of his Indian territories to the Mauryan Empire in exchange for 640 war elephants—a significant move that highlights the interconnectedness of the Hellenistic world with other contemporary empires. These elephants would later play a crucial role in Seleucus’s efforts to consolidate his rule in the western parts of his domain, particularly at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BCE. This exchange also underscores the pragmatic aspects of diplomacy and the value placed on military assets over territorial possession.

The relationship between the Hellenistic kingdoms and the Mauryan Empire was not merely transactional but also reflective of a broader cultural and intellectual exchange. The Mauryan kings, including Ashoka the Great, viewed the Hellenistic world with a mixture of admiration and pragmatism. Ashoka, in his edicts, mentions contacts with the Greek world, including Antiochus II Theos of the Seleucid Empire, illustrating the diplomatic engagements between these great civilizations. The Mauryan perspective on the Hellenistic kingdoms was likely influenced by both the military prowess and the cultural achievements of the Greeks, as well as by the opportunities for trade and intellectual exchange that these contacts facilitated.

The Emergence of Stability

Out of the initial period of conflict and fragmentation, the Hellenistic world began to stabilize around these three major kingdoms, each contributing uniquely to the era’s character. Macedon, retaining its traditional role as a military powerhouse, continued to exert influence over the Greek city-states. The Seleucid Empire, with its vast territories spanning from the Aegean Sea to the Indus Valley, served as a bridge between the Greek and Eastern cultures, facilitating the exchange of ideas, goods, and technologies. Egypt under the Ptolemies became a centre of learning and culture, with Alexandria hosting the famed Library and the Museum, attracting scholars from across the known world.

This new phase of stability allowed for the flourishing of the Hellenistic culture, characterized by advancements in science, philosophy, and the arts. The blending of Greek and Eastern elements gave rise to a vibrant cultural synthesis that would leave a legacy on subsequent civilizations.

The Hellenistic period, therefore, was not just a time of political machinations and military conflicts but also a remarkable era of cultural and intellectual exchange. The interactions between the Hellenistic kingdoms and other contemporary powers like the Mauryan Empire played a crucial role in shaping the trajectory of world history, demonstrating the interconnectedness of ancient civilizations and their contributions to the global heritage.

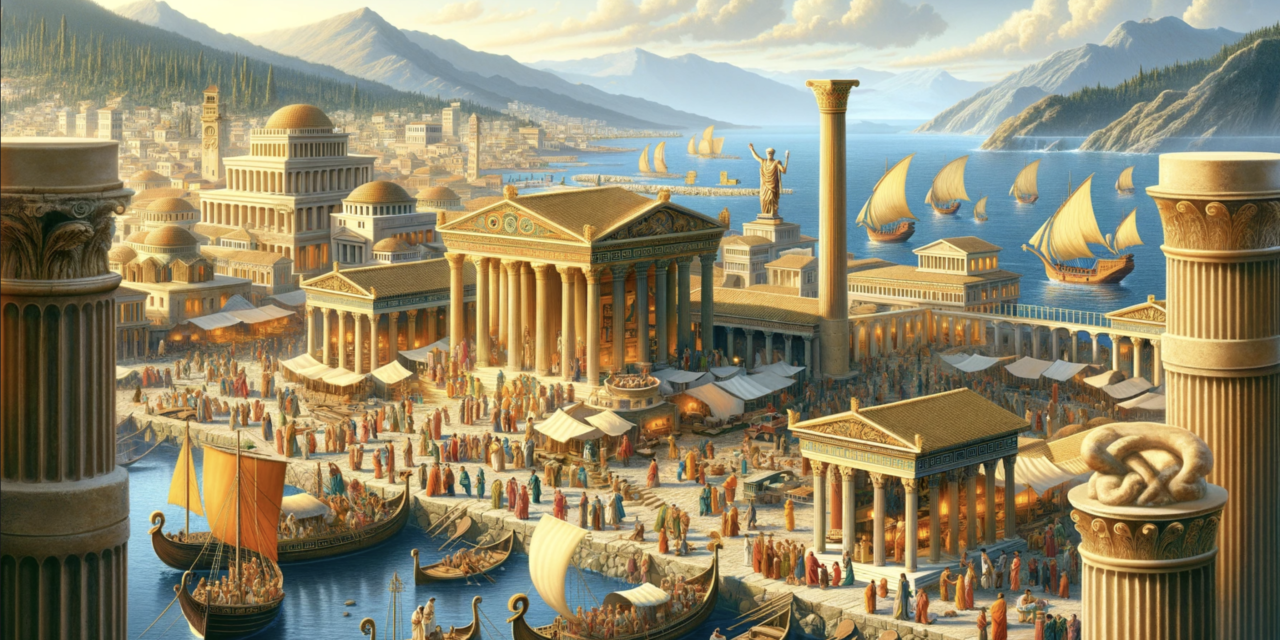

Life in the Hellenistic World: Routes, Cities, and Cultural Fusion

A dynamic interplay of military conquests, economic expansion, and cultural exchange characterized the Hellenistic period. This was a time when the legacy of Alexander’s expeditions continued to reshape the ancient world, giving rise to a new cultural and social landscape.

Trade Routes and the Establishment of New Cities

As Alexander’s armies carved paths across territories, they inadvertently laid the foundation for a network of trade routes that would connect distant regions. These routes followed the march of the armies, establishing lines of supply that would later serve as channels of trade. Macedonian, Roman, Persian, and even Mongolian conquests facilitated some of the earliest forms of cultural exchange through these trade networks.

The rise of new cities along these routes marked a significant transformation from the classic Greek polis to urban centres of commerce within a broader state structure. These cities, often founded by or thriving due to the influence of retired Macedonian soldiers, became melting pots where ideas, goods, and people from diverse backgrounds interacted and integrated. Trade flourished, leading to an era where scholarship and intellectual pursuits broadened horizons, influenced heavily by the spread of the Greek language and culture.

The Emergence of the Cosmopolis

The Hellenistic period witnessed the dismantling of the city-state system and the rise of the cosmopolis—a concept of a ‘world-city’ that transcended traditional political borders. This notion embodied the ideal of a universal city, often governed by a Greek overseer, but with local authorities in charge of regional affairs. It was a time when the idea of a ‘world-state,’ united by the commonality of Hellenic language and culture, began to take root.

Cultural Fusion and Philosophical Universality

The cultural dynamics of the Hellenistic world can be likened to both a “melting pot” and a “salad bowl,” where Macedonian cultural elements mixed with local traditions. Retired Macedonian soldiers married local women, and local residents were conscripted into the Macedonian army, leading to a rich tapestry of cultural identity.

This period also saw the beginnings of what some might identify as the West becoming ‘WEIRD’ (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic), marked by the breaking down of traditional family and clan systems. The relevance of this transformation resonates with contemporary societies, including the UK, where the impact of individualism and social change remains a subject of discussion.

The philosophical landscape of the Hellenistic world was dominated by the search for universality and the therapeutic treatment of the individual soul. Philosophy was not just an academic pursuit but was seen as a ‘way of life.’ The era was marked by the prominence of three main philosophical schools: Stoicism, which emphasized virtue and self-control; Epicureanism, which advocated for pleasure and the avoidance of pain; and Scepticism, which questioned the possibility of certain knowledge.

In the religious sphere, there was a notable tolerance of multiple belief systems, reflecting the diversity and inclusiveness of the Hellenistic world. This pluralism allowed various ‘religions’ and cults to coexist, often syncretizing Greek and local deities and practices.

The Zenith of Hellenistic Science and Technology: The Library at Alexandria

The Hellenistic age was not only a period of great military and political feats but also a remarkable era for science and technology. At the heart of this intellectual flourishing was the Library at Alexandria, not merely a repository of scrolls but a vibrant center of learning and scholarship. Funded by the state, this institution attracted the greatest minds of the era, becoming the crucible for scientific and mathematical advancements that would shape the future of human knowledge.

The Beacon of Knowledge

The Library at Alexandria transcended the concept of a library as we understand it today—it was a research institution where scholars were financially supported by the state, fostering an environment where academic pursuits could thrive. This patronage resulted in an unprecedented assembly of intellects, including:

- Euclid, whose ‘Elements’ formulated the basis for geometry as it is still taught. His work on geometric shapes, solids, theorems, and axioms through deductive reasoning, as well as his contributions to the understanding of prime numbers, laid the foundation for modern mathematics.

- Archimedes, who provided the world with the Principle of Buoyancy, the Lever Law, and practical inventions such as the Archimedes screw and compound pulleys. His work extended into theoretical explorations in ‘On the Sphere and Cylinder’, ‘On Spirals’, and ‘On Floating Bodies’, and he made significant advancements in calculating the approximate value of pi.

- Eratosthenes, named ‘The Father of Geography’, authored the ‘Geographika’, introducing the concepts of latitude and longitude. His map-making innovations and the development of the ‘Sieve of Eratosthenes’ for identifying prime numbers were complemented by his remarkably accurate calculation of the Earth’s circumference.

Astronomy: The Hellenistic Pursuit of the Heavens

Astronomy, crucial to governance and daily life, was another field that reached new heights during the Hellenistic period. It was essential for timekeeping, navigation, trade, and the affirmation of political power and prestige. Beyond its practical applications, astronomy also played a significant role in scientific inquiry and spiritual life through astrology and divination.

The ‘Almagest’ by Ptolemy emerged as the definitive work on celestial movements, remaining influential until the Renaissance. Moreover, the discovery of the Antikythera mechanism—a sophisticated analogue computer designed to calculate astronomical positions—exemplified the remarkable technological ingenuity of the time.

The Legacy of Hellenistic Science

The Library at Alexandria, thus, was emblematic of the Hellenistic era’s spirit, where the pursuit of knowledge was honoured and innovators like Hypatia continued the tradition of scientific inquiry. The insights gained from this period laid the groundwork for future scientific endeavours, underscoring the profound influence of Hellenistic scholars on the trajectory of human civilization.

An Epochal Transition: From Hellenistic to Roman Dominance

As we reflect on the tapestry of the Hellenistic world, our narrative finds its epilogue in the emergence of a new power: Rome. It was a poignant moment when the first Emperor of Rome, Augustus, paid homage at Alexander’s tomb—a symbolic act representing not only the reverence for Alexander’s legacy but also the subtle passing of the torch from the Hellenistic age to the Roman era.

The Roman Ascendancy

The Roman conquest of the Hellenistic kingdoms was gradual but inexorable, marked by strategic annexations and the astute application of political power. The Battle of Actium in 31 BCE, which solidified Augustus’s control over the empire, effectively spelled the end of the Hellenistic period as the last of the Ptolemaic dynasty fell to Rome.

Cultural Preservation and Transformation

Despite the political and military shifts, the Hellenistic culture did not vanish; rather, it was absorbed and preserved within the fabric of Roman civilization. The Romans, known for their pragmatism, recognized the profound advancements in art, science, philosophy, and governance that had emerged from the Hellenistic world. They embraced and perpetuated this heritage, ensuring that the Hellenistic influence would continue to enrich Roman culture.

The administrative systems, city planning, and even aspects of Hellenistic art and philosophy were integrated into the Roman way of life. Greek became the lingua franca in the eastern provinces of the Roman Empire, and the intellectual pursuits initiated in the Hellenistic period continued to find a place within Roman society.

A Legacy Undimmed

Thus, while the sovereignty of the Hellenistic kingdoms was superseded by the might of Rome, the spirit of the Hellenistic age—a spirit of innovation, cultural exchange, and intellectual curiosity—lived on. It endured throughout the expanse of the Roman Empire, shaping its cultural and intellectual contours and leaving an indelible mark on the annals of history.

As we conclude, we see that the Hellenistic world, with all its complexities and contributions, was not extinguished by Roman conquest. Instead, it was transformed, its essence diffused throughout a new empire that would carry the torch of its culture for centuries to come.

Terry Cooke-Davies

23 March 2024

Special thanks to the AI assistance provided by Perplexity and ChatGPT (4) from OpenAI for offering insights and suggestions that helped shape this article.