Introduction

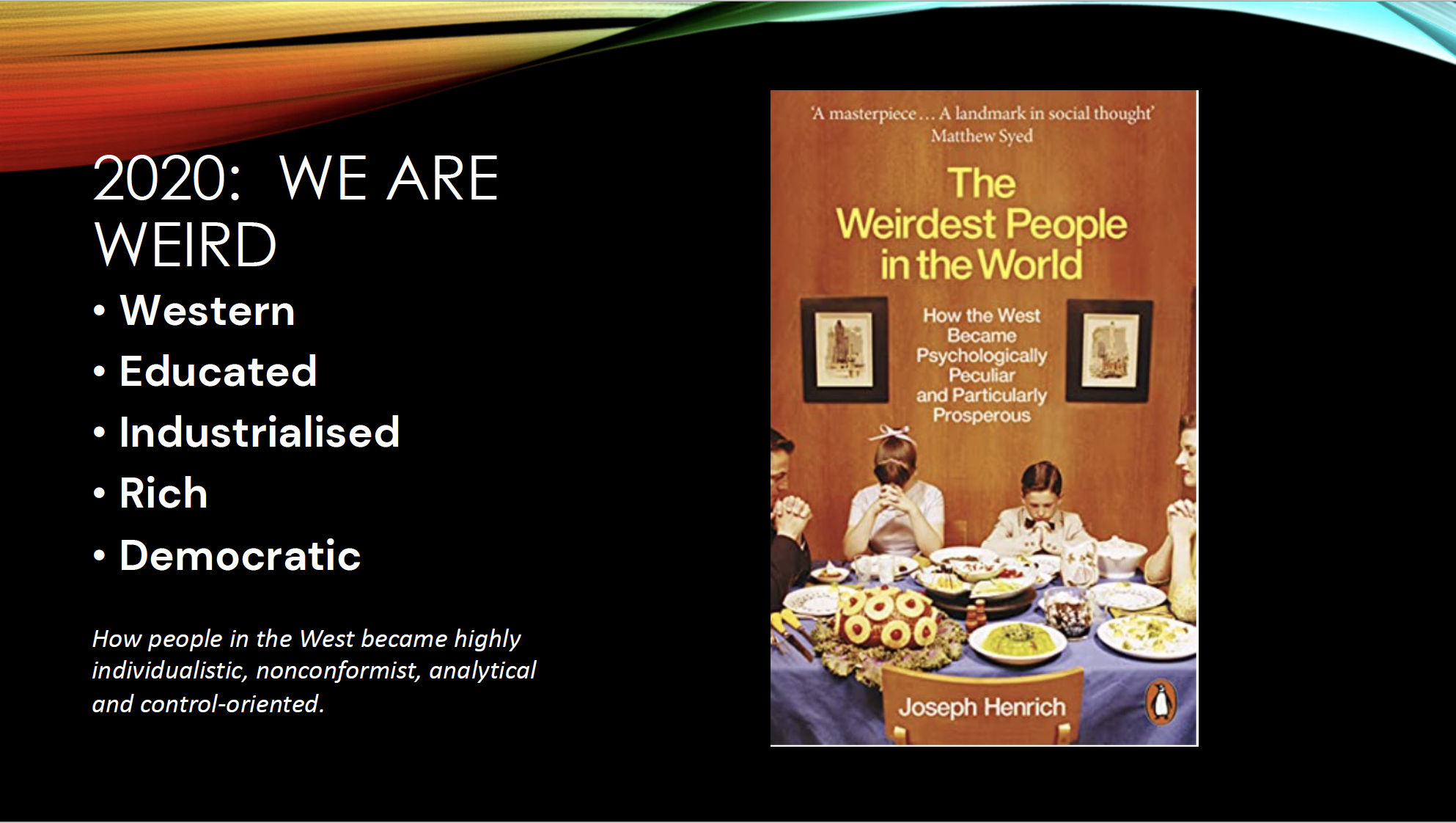

In today’s world, the period we are reviewing is perhaps the crucial period of history, as the current war in Ukraine and the recent meeting between Presidents Xi and Putin reinforce. In an article in “The Times” on March 21 2023, former Foreign Secretary William Hague writes, “According to polling last autumn, 87 per cent of the 1.2 billion people who live in liberal democracies held a negative view of Russia; 75 per cent also thought negatively of China. But the two dictators meeting this week are playing to a different audience: the views of the more than 6 billion people who live outside our democracies are the exact opposite. Months into Moscow’s murderous war, large majorities thought positively of Russia in South Asia (75 per cent), Francophone Africa (68 per cent) and Southeast Asia (62 per cent). What has become known as the global south, including many increasingly important and populous states, just doesn’t think our way.”

He doesn’t mention that the 1.2 billion people (16% of the world’s population) who, like us, live in liberal democracies collectively account for over 60% of the world’s wealth, as measured by GDP.

This article will consider and discuss how we came to think “our way” and become so wealthy.

Summary

The period from the middle of the 16th to the end of the 18th century saw significant changes in many areas of life that laid the foundations for the modern era:

- Political: The rise of nation-states, the growth of centralized power, and the development of constitutional governments were critical political changes that shaped the modern world.

- Economic: The growth of trade and commerce, the rise of capitalism, and the Industrial Revolution transformed the world economy and created the conditions for the modern market system.

- Scientific and Technological: The scientific revolution and the development of new technologies, such as the printing press, steam engines, and textile machinery, transformed how people lived and worked.

- Cultural: The Enlightenment and the rise of individualism were social movements that challenged traditional ideas and values and helped to shape the modern world.

These ideas didn’t simply arrive “out of the blue”. Many scientific discoveries grew from ideas fermented in Baghdad and elsewhere during the Golden Age of Islam, as we saw in “The Roots of Modern Science”. And embryonic ideas about democracy had already emerged in medieval Christendom. In 11th-century Cistercian monasteries, for example, monks elected their abbot from among their number. Meanwhile, although some cities were governed by councils comprising merchant oligarchies, elsewhere, the governing bodies were expanded to include members of many organizations, such as guilds, who increasingly pressed for representation. Joseph Henrich describes the process in his book “The Weirdest People in the World”, subtitled “How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous”.

This article will review the two overlapping periods, which are frequently referred to as the “Scientific Revolution” (circa 1550 to 1700) and the “Enlightenment” (circa 1650 to 1800).

The “Scientific Revolution”

Five “Big Ideas”

Although the term “Scientific Revolution” is now falling out of use as historians and scholars acknowledge the role played by Islamic science during the Middle Ages, the period from 1550 to 1700 saw the emergence of significant new ideas that nourished the development of science and helped it become what it is today.

Five ideas, in particular, revolutionized how people thought about the world and provided the backbone for the modern scientific method.

Empiricism

Empiricism is the idea that knowledge should be based on observation and experience. The English philosopher Francis Bacon was one of its most prominent champions. Bacon believed we should learn through systematic observation of the natural world. This idea paved the way for the development of the scientific method.

Scientific Method

The scientific method is a systematic approach to the acquisition of knowledge. This approach involves observing the natural world, formulating hypotheses, testing those hypotheses through experiments, and analyzing the results. The Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei pioneered the method and used it to make groundbreaking discoveries about the nature of the universe.

Mathematical Modelling

Mathematical modelling is the use of mathematical equations to describe natural phenomena. This idea was developed by the French mathematician René Descartes. Descartes believed that the natural world could be understood through mathematical models. This idea was crucial for the development of modern physics.

Laws of Nature

The idea of laws of nature emerged from the scientific revolution. This idea holds that universal laws govern natural phenomena and can be discovered through scientific investigation. The English physicist Isaac Newton gave the idea substance when he formulated the laws of motion and the law of universal gravitation.

Mechanistic View of the Universe

The mechanistic view of the universe likens the workings of the natural world to those of a machine. The French philosopher and mathematician René Descartes developed this idea. He believed that the natural world could be understood through cause-and-effect relationships. This idea was influential in developing modern physics and the concept of determinism.

The Scientific Method in Action

To gain an idea of the scientific method in action, consider one of the most famous examples of its success: the development of the heliocentric model of the solar system.

As the example shows, it is not simply a process involving one individual, but it provides a framework whereby different people in different countries can refine and develop a theory and provide evidence of its correctness.

The Polish astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus put forward the heliocentric model of the solar system in 1543. He developed this model based on observations he had made of the movements of the planets in the sky, making extensive use of insights and measurements from Islamic astronomers. However, Copernicus’ model had some flaws and could not fully explain the movements of the planets.

In the mid-16th century, the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe made a series of observations of the movements of the planets, which were much more accurate than those made by Copernicus. They revealed some discrepancies in the heliocentric model and, for example, showed that the planet Mars did not move in the way that the heliocentric model predicted.

Johannes Kepler, a German astronomer who worked with Brahe, used Brahe’s observations to develop his laws of planetary motion in the early 1600s. Kepler’s laws explained the planets’ movements more accurately than Copernicus’ model by showing that the planets moved in elliptical orbits around the Sun rather than circular ones, as Copernicus had believed.

In 1609, the Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei used a telescope to observe the moons of Jupiter. Galileo’s observations provided further evidence for the heliocentric model and showed that not all celestial bodies orbited the Earth.

In 1687, Isaac Newton published his Principia Mathematica, which provided a mathematical explanation for the movements of the planets based on the laws of physics. Newton’s laws of motion and universal gravitation explained the planets’ behaviour in a way consistent with the heliocentric model as modified by Keppler and Galileo.

In 1742, French astronomers and geographers carried out a scientific expedition to Peru to measure the shape of the Earth. Their measurements finally confirmed the heliocentric model’s accuracy nearly two hundred years after Copernicus proposed it.

Not unreasonably, scientific discoveries tend to be linked in the popular imagination with the names of those most closely associated with their discovery – for example, the “Copernican Revolution” or “Newton’s Laws of Motion”. But this should not be allowed to disguise the fact that science is a truly global enterprise, with facts being equally valid in all parts of the world, regardless of the beliefs or culture from which they emerge. As Professor Jim Al-Khalili remarks in his video “Science and Islam”, “Nature’s rules are refreshingly free from human prejudice.”

Advances in multiple fields

The “Scientific Revolution” saw a significant shift in how people viewed the natural world and its processes. Many discoveries and inventions during this time have profoundly impacted our understanding of the world and continue to shape modern scientific thought. They include the following:

Astronomy

One of the most significant scientific advances of the scientific revolution was the heliocentric theory, proposed by Nicolaus Copernicus in 1543. The heliocentric model replaced the previously accepted geocentric view, which held that the Earth was the centre of the universe, and all other celestial bodies revolved around it. The heliocentric theory postulated that the Sun was at the centre of the universe, and all other planets revolved around it. This theory revolutionized astronomy and paved the way for discoveries such as Johannes Kepler’s laws of planetary motion and Galileo Galilei’s telescopic observations of the Moon and planets.

Physics

The scientific revolution also saw significant advancements in the field of physics. One of the most notable was the development of Isaac Newton’s laws of motion and his law of universal gravitation. Newton’s laws of motion provided a mathematical framework for understanding the behaviour of objects in motion. In contrast, his law of universal gravitation explained the attraction between all items in the universe. These laws paved the way for further advancements in physics, including the development of calculus and the study of electromagnetism.

Chemistry

Chemistry also saw significant advancements during the scientific revolution, with the development of new theories and discoveries. One of the most important was the law of conservation of mass, proposed by Antoine Lavoisier in 1789. This law states that mass is neither created nor destroyed in chemical reactions but merely changes form. Lavoisier’s work also led to the development of the modern chemical nomenclature system, which people still use today.

Biology

In the field of biology, one of the most notable was the development of the microscope, which allowed scientists to observe microorganisms for the first time. This led to the discovery of many new species and the development of the germ theory of disease, which postulates that microorganisms cause many illnesses. Other significant advancements in biology during the scientific revolution include the classification of living organisms by Carl Linnaeus and the discovery of oxygen by Joseph Priestley.

Medicine

The scientific method was also applied to medicine, emphasizing the importance of experimentation, observation, and data collection. This led to new medical treatments and practices, such as vaccines and anaesthesia.

One of the most influential medical figures during the scientific revolution was Andreas Vesalius, the founder of modern human anatomy. Vesalius’s groundbreaking work on human anatomy challenged the previously accepted theories of the Greek physician Galen and paved the way for further advancements in medical knowledge and treatment.

Another significant advancement in medicine during the scientific revolution was the discovery of blood circulation by William Harvey. Harvey’s work challenged the previously accepted ideas about blood movement in the body and led to the development of new treatments for cardiovascular diseases.

In addition to these discoveries, the scientific revolution also saw significant advancements in the field of pharmacology. One of the most important was the development of quinine, a medication used to treat malaria. Jesuit missionaries discovered quinine in South America, and it was later refined and synthesized for widespread use.

Sir Isaac Newton: a scientific colossus

Sir Isaac Newton (1642-1727) was one of the most influential scientists in history. His work laid the foundation for modern physics and mathematics. He was a mathematician, physicist, and astronomer who made numerous groundbreaking contributions to the development of science and our understanding of the world. He is particularly noteworthy in the context of this article because he was seen as a towering colossus, standing astride both the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment.

Early Life and Education

He was born in Woolsthorpe, England, on December 25, 1642. His father died just a few months before his birth, leaving his mother to raise him and his two siblings. Newton was a shy and introverted child, and he showed a talent for mathematics and science from a young age.

In 1661, Newton entered Trinity College, Cambridge, where he studied mathematics, astronomy, and physics. At Cambridge, he developed his ideas about calculus, optics, and the laws of motion.

Contributions to Science

One of his most significant contributions to science was the development of the laws of motion. In his book “Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy,” also known as the “Principia,” Newton outlined his three laws of motion. These laws describe the behaviour of objects in motion and provide a mathematical framework for understanding the behaviour of objects in the physical world. They are still widely used and considered a cornerstone of modern physics.

Newton’s work also led to the law of universal gravitation. This law states that all objects in the universe attract each other with a force proportional to their mass and the distance between them. This law explained many phenomena in astronomy, such as the motion of the planets and the tides. It provided a framework for understanding the behaviour of objects in the universe.

Another significant contribution of Newton was the development of calculus, a mathematical system used to analyze and describe the relationships between changing quantities. Calculus is widely used today in physics, engineering, and other fields.

Newton also made significant contributions to the field of optics. He discovered that white light was composed of different colours, which he demonstrated using a prism. He also developed the reflecting telescope, allowing more accurate observations of the stars and planets.

Legacy

Newton’s work laid the foundation for modern physics and mathematics. His ideas continue to shape our understanding of the world. His laws of motion and law of universal gravitation continue to be used in physics today, and calculus is still a fundamental tool in many fields.

Newton’s work also significantly impacted the development of science as a discipline. His emphasis on experimentation, observation, and data collection laid the foundation for the scientific method, which is still used today in scientific research.

His work, perhaps more than that of any other, fuelled the image of the universe as a giant machine, with all its component elements functioning together like a well-built clock. Within this worldview, which came to prominence during the Enlightenment, God became more of a distant figure who had created the world but did not interfere with its workings on a day-to-day basis. This shift in thinking was driven by the growing influence of science, which emphasized natural laws and causes, and the increasing focus on human reason and autonomy.

Enlightenment thinkers tended to view God as a rational and benevolent being who had created the universe according to specific laws but who did not intervene in its operations. This view of God as a distant, hands-off creator is sometimes called “deism.”

However, it’s important to note that not all Enlightenment thinkers shared this view of God. This period encompassed a wide range of beliefs and attitudes toward religion and spirituality. Additionally, the idea of God as a “Deus ex machina” does not necessarily mean that God was seen as an absent or unimportant force in the world; instead, it suggests that God’s role in the world was seen as less direct and more mediated through natural laws and human agency.

The Enlightenment

Overlapping with and strongly influenced by the scientific revolution was a development in philosophy which was to reshape the political and intellectual climate in many parts of the world, leading ultimately to the constellation of ideas known in the West as “liberal democracy”. The name thought leaders in France, Britain, Germany and the United States gave to it was “the Enlightenment”.

The Enlightenment “project.”

The Enlightenment was a period of intellectual and cultural transformation in Europe during the 18th century. It was characterized by a belief in reason, progress, and the power of knowledge to improve society. Anthony Pagden, a prominent historian of the Enlightenment, described it as a project to describe and define humankind in the same way that the natural sciences sought to describe and explain the natural world.

The first hypothesis identified by Pagden is that humans are unique among animals and share nothing in common with divinity. Enlightenment thinkers maintained that human beings are capable of reason and that reason should be the guiding principle of society. They rejected traditional sources of authority, such as religion and monarchy. Instead, they embraced the idea of individual liberty, equality, and democracy.

Enlightenment thinkers believed that humans were capable of progress and that society could be improved by applying reason and knowledge. They advocated for scientific inquiry, empirical observation, and experimentation to understand the natural world and improve the human condition. This emphasis on reason and the natural world was evident in the works of scientists such as Isaac Newton and philosophers such as John Locke, who argued that all humans had natural rights to life, liberty, and property.

The second hypothesis identified by Pagden is that there exists a universal “human nature”, and all human beings desire a shared and universal social and political life in the “cosmopolis”. This hypothesis reflected the Enlightenment’s belief in the universality of human values and the possibility of a shared human experience. Enlightenment thinkers argued that human beings were not bound by cultural or religious differences but shared a common humanity that transcended these differences.

Enlightenment thinkers believed that human beings were capable of creating a society that was just, egalitarian, and based on reason. They advocated for the abolition of slavery, the emancipation of women, and the establishment of democratic institutions. They believed that a shared human experience could be achieved through the creation of a “cosmopolis”, a society in which all human beings could live together in harmony, free from the constraints of cultural or religious differences.

“Philosophes” and the Encyclopédie

No discussion of the Enlightenment would be complete without reference to the “philosophes”. They were a group of 18th-century French intellectuals who sought to apply the principles of the Enlightenment to reform society. They believed in the power of reason, education, and progress to create a more just and egalitarian society. The philosophes were critical of traditional sources of authority, such as religion and monarchy. They advocated for individual liberty, equality, and democracy.

The most notable work of the philosophes was the Encyclopédie. This comprehensive reference work aimed to summarize all human knowledge and promote the principles of the Enlightenment. It was edited by Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert and published between 1751 and 1772. It comprised 28 volumes and included articles on subjects ranging from philosophy and science to technology and the arts.

The Encyclopédie was a significant achievement of the Enlightenment. It played a crucial role in promoting the principles of reason, progress, and knowledge. It aimed to disseminate knowledge to a broad audience and was instrumental in spreading the ideas of the Enlightenment beyond the circles of the elite. The Encyclopédie was also notable for its critical approach to religion and traditional sources of authority. It challenged the Catholic Church and the monarchy and advocated individual liberty and democratic institutions.

The Encyclopédie was not without controversy, and its publication faced opposition from both the Catholic Church and the monarchy. The Church condemned the Encyclopédie as atheistic and subversive, and the monarchy attempted to suppress its publication. However, the Encyclopédie was widely read and influential, and it played a significant role in promoting the ideas of the Enlightenment.

Three patron saints of the Enlightenment

Three figures who played a significant role in the development of the Enlightenment were Francis Bacon, Isaac Newton, and John Locke. They were known as the patron saints of the Enlightenment for their contributions to philosophy, science, and politics, respectively.

Francis Bacon (1561-1626) was an English philosopher, scientist, and statesman widely regarded as the founder of the scientific method. He emphasized the importance of empirical observation and experimentation in understanding the natural world. Bacon believed knowledge should be based on observation and experience rather than tradition and authority. His ideas laid the foundation for the scientific revolution, which profoundly impacted the development of science and the Enlightenment.

Isaac Newton (1642-1727) was an English physicist and mathematician whose contributions to science have been explored above. His presence as a “patron saint”, however, indicates the profound impact the development of science had on the Enlightenment.

John Locke (1632-1704) was an English philosopher and political theorist who believed that individuals had natural rights to life, liberty, and property and that governments existed to protect these rights. Locke’s ideas profoundly impacted the development of political theory and were instrumental in shaping modern political thought.

Voltaire dedicated the most serious of his “lettres” to these three. D’Alembert and Diderot dedicated the Encyclopédie to them. In 1789, Thomas Jefferson, the principal author of the Declaration of Independence, ordered a composite portrait of the same three Englishmen.

“They have laid the foundation for the physical and moral sciences of modernity … The three greatest men that ever lived, without any exception.”

Enlightenment “social media.”

Two institutions that played a significant role in the development of the Enlightenment were salons in continental Europe and coffee shops in London. They were the “social media” of the Enlightenment, providing a space for intellectual exchange and the dissemination of ideas. This article will explore the salons in continental Europe and coffee shops in London and their role in the development of the Enlightenment.

Salons in Continental Europe

Salons were gatherings of intellectuals, artists, and socialites in private homes in Paris and other cities in continental Europe. They were typically hosted by wealthy women who invited guests to engage in intellectual discussions and cultural activities. Salons provided a space for the exchange and dissemination of ideas.

Salons were often focused on literature, philosophy, and politics. They were a forum for the exchange of ideas and the discussion of contemporary issues. Salons were also a place where new ideas were introduced and debated, and intellectuals could network and form alliances.

Salons were an important institution for women in the 18th century, providing a space for them to engage in intellectual pursuits and participate in the cultural life of their society. Women played a significant role in hosting and participating in salons, and many influential women of the Enlightenment were associated with these gatherings.

Coffee Shops in London

Coffee shops were influential in the development of the Enlightenment in London. They were places where men could gather to drink coffee, read newspapers, and engage in intellectual discussions. Coffee shops facilitated the dissemination of ideas, and many influential figures of the Enlightenment were associated with these establishments.

Like salons, coffee shops were often focused on politics, philosophy, and literature. They were where new ideas were introduced and debated, and intellectuals could network and form alliances. Coffee shops were also a forum for discussing contemporary issues. They played a significant role in shaping public opinion in London.

The Age of Revolution

The Enlightenment promoted the principles of reason, progress, and knowledge, challenging traditional sources of authority, such as religion and monarchy. It emphasized the importance of individual liberty, equality, and democracy, and it advocated for the abolition of slavery, the emancipation of women, and the establishment of democratic institutions. The Enlightenment was a period of intellectual and cultural transformation that paved the way for significant political and social change.

However, the ideas of the Enlightenment also challenged the existing political and social order, and they often met with resistance from traditional sources of authority. The French Revolution was the most significant of the revolutionary movements that occurred during this period. It was a period of political and social upheaval in France from 1789 to 1799 that saw the overthrow of the monarchy, the establishment of democratic institutions, and the promotion of the principles of liberty, equality, and fraternity.

The French Revolution was a direct result of the Enlightenment’s ideas, fuelled by the belief in reason, progress, and the power of knowledge to improve society. It sent shockwaves throughout the Western world and profoundly impacted the development of modern democracy and human rights.

The Enlightenment’s ideas significantly influenced the American Revolution from 1765 to 1783. The American Revolution (known in the UK as the “War of Independence”) was a period of political and social change that led to the United States establishment as an independent nation. It promoted individual liberty, equality, and democracy. It was fueled by the belief in reason, progress, and the power of knowledge to improve society.

Enlightenment Today

The legacy of the period covered by this article is all around us today. But it is also a matter of controversy. Thinkers such as cognitive scientist Stephen Pinker (“Enlightenment Now”), political scientist Francis Fukuyama (“Liberalism and its Discontents”) and philosopher A. C. Grayling (“For the Good of the World”) believe that enlightenment values are under threat in one way or another and need strengthening. They believe values of reason, science, individualism, humanism, and critical thinking are essential for creating a more just, fair, and prosperous world. They argue that defending these values is necessary for promoting progress, preserving democracy, preventing authoritarianism, and promoting global peace and stability.

On the other hand, given the extent of the current human predicament, there are serious questions about several of the Enlightenment’s most cherished ideas. Some prominent thinkers argue that while the Enlightenment values have been valuable and important, they are not without their flaws and limitations. We should re-examine and modify them for the current era.

In “The Enigma of Reason”, Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber argue that “reason” is a social capability rather than an individual aptitude, which suggests that adversarial debate as practised in Parliament and Lawcourts needs a fundamental rethink. David Graeber and David Wengrow, in their book “The Dawn of Everything”, believe that the Enlightenment emphasis on reason and rationality has been used to justify oppressive social structures, such as capitalism and imperialism, so we should re-examine and modify them to create a more just and equitable society.

More fundamentally, Iain McGilchrist in “The Matter with Things” provides copious evidence that in prioritizing the rational, model-making, and mechanistic aspects of the world and losing all contact with the mysterious, sacred and holistic elements, we are misusing our brains’ natural capabilities to the detriment of our place in the Earth’s ecology. He believes we must re-examine and modify Enlightenment values to create a more holistic, integrated understanding of the world.

The War in Ukraine

Nowhere is this topic’s importance more visible and pressing than in Ukraine. In February 2022, Russian Forces mounted a full-scale invasion of Ukraine in a flagrant violation of Ukrainian sovereignty. And yet, as the paragraph at the opening of this article makes clear, only a minority (16%) of the world’s population – the minority that has embraced the ideas and values of the Enlightenment – hold a negative view of Russia’s actions, and of China which supports Russia.

It is indeed no coincidence that this same minority of nations, which between them also account for over 60% of the world’s GDP, became wealthy through the fruits of the industrial revolution and European imperialism. One author, who we touched on briefly in Module 3 (“The Geography of Thought”), offers an analysis of how the conditions in Medieval Europe provided precisely the right conditions for the ideas of the Enlightenment to lead to the distinctive values that are embodied in modern “Western” democracy.

In his “Times” article, William Hague argues that “We have to adjust to the idea that most of the world does not see things our way.” He points out that “Our view of a binary choice between democracy and autocracy is seen as self-serving, and ceaseless Russian propaganda is believed [in the “Global South”, from claims of attacks on Russian civilians, to Nato aggression, to US experiments with biological warfare labs in Ukraine.” Nevertheless, he argues, “We can do more, without breaching any principle, to step up both communication and genuine partnership with the global south.”(William Hague, West Can Stop the World Falling for Xi and Putin). This is undoubtedly correct. Despite our wealth (or perhaps even because of it), we cannot impose our views of the world on the overwhelming majority that does not “think like us”.

In the meantime, humanity faces a tangled mess of challenges that include climate change, habitat loss, biodiversity loss, environmental pollution, overuse of resources and growing inequality. What you might call the “human predicament”. Suppose we hope to make headway with these in the time available. In that case, we need to settle down to the serious business of understanding people who think differently from ourselves.

Let’s start to talk and think together.

Terry Cooke-Davies

April 2023