The Journey So Far

For over two and a half years, our u3a group has explored how to make sense of our world through examining history, science, and different cultural perspectives. We’ve traced developments from ancient civilisations through today’s scientific understanding, discovering a universe far stranger and more interconnected than any single tradition imagined. We’ve learned we’re literally made of elements forged in stars, that consciousness emerges from neural networks of staggering complexity, and that we exist within webs of relationship spanning from quantum to cosmic scales.

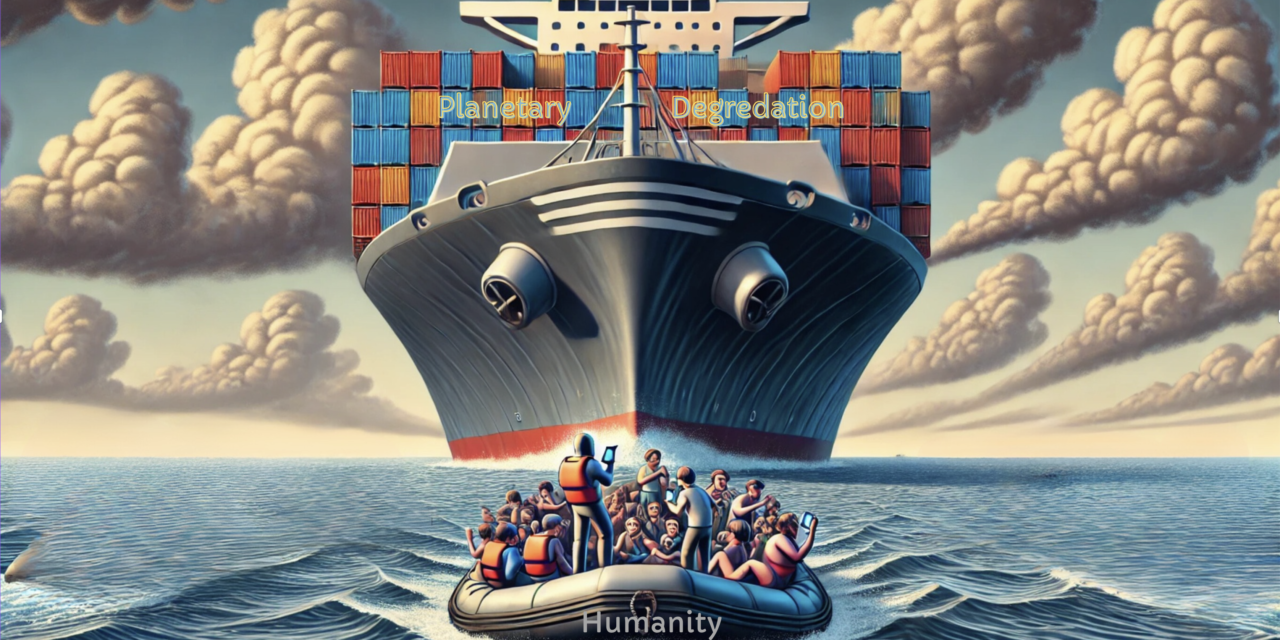

But this journey leaves us with urgent questions. Science shows us what is – our cosmic origins, our evolutionary heritage, our ecological embeddedness. Yet it struggles to tell us what this means for how we should live. This gap becomes critical when facing climate change, biodiversity collapse, social fragmentation, and potential nuclear conflict. We don’t have centuries to figure this out. The timescale for transformation is measured in years, not generations.

This is why philosophy becomes essential – not as academic exercise but as emergency navigation for a species trying to avoid catastrophe.

The Coherence Problem

Many of us live with internal contradictions that undermine our effectiveness. Consider trying to hold both an engineering education grounded in materialism and spiritual beliefs about consciousness or meaning. When different parts of our worldview conflict, we experience stress, anxiety, and paralysis. This matters because incoherent worldviews prevent coherent action, and we desperately need coherent action at planetary scale.

Every worldview rests on four pillars that must work together:

- Ontology: What exists? Is reality just matter and energy, or does consciousness, meaning, or spirit have independent existence?

- Epistemology: How do we know? Can we trust only scientific observation, or are intuition and spiritual insight valid sources of knowledge?

- Ethics: How should we live? What matters most? What are our obligations to others and to future generations?

- Praxis: How do we act? Do our daily choices reflect our stated values?

The coherence test asks whether these pillars support each other or pull in different directions. Can you live by your stated beliefs without constant contradiction?

Three Ways of Knowing

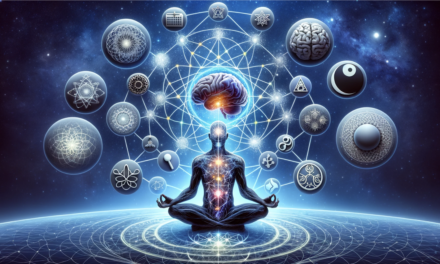

Humanity has developed three main approaches to understanding reality, each valuable but limited.

Science provides powerful, reliable knowledge through empirical observation and testing. It has given us medicine, technology, and deep understanding of physical processes. But science pretends we can stand outside reality as objective observers. It struggles with consciousness, meaning, and values. Most critically, it cannot derive “ought” from “is” – no amount of climate data tells us we should prevent catastrophe.

Spirituality offers direct experiences of unity, transcendence, and meaning. It addresses precisely what science cannot – purpose, value, and our felt sense of connection. But spiritual insights can’t be empirically verified, often resist clear articulation, and can be hijacked for oppression. How do we distinguish wisdom from delusion when experiences are inherently subjective?

Philosophy attempts to integrate both, using reason to bridge different ways of knowing. It can work with both logical analysis and paradox. But philosophy faces the self-referential problem of consciousness examining itself, and language can smuggle in hidden biases.

Intelligence can be regarded as relational participation rather than individual possession – emerges through relationship and exchange across scales.

How Science Actually Works

Understanding how science progresses helps us grasp our current situation. Karl Popper showed that scientific theories advance through falsification – we can’t prove theories true, but we can prove them false. Scientists should actively try to disprove their hypotheses. Thomas Kuhn revealed a different pattern: scientists mostly work within accepted paradigms, solving puzzles rather than questioning foundations. Only when anomalies accumulate do revolutionary paradigm shifts occur, changing how we see everything.

Both are right at different levels. Day-to-day science follows Popper’s rules within paradigms, but the paradigms themselves shift through Kuhnian revolutions. Einstein’s relativity didn’t just add to Newton’s physics – it revolutionised our entire conception of space, time, and gravity.

We may be facing a similar revolution in worldview. Climate change, mass extinction, and social breakdown aren’t just problems to solve within existing paradigms. They’re anomalies revealing that our fundamental assumptions about progress, growth, and humanity’s relationship with nature are catastrophically wrong.

The Integration Challenge

Can we integrate scientific and spiritual perspectives into coherent worldviews? The challenge seems immense. Science has no obvious place for transcendent experience. Many spiritual traditions struggle with evolution and neuroscience. Yet perhaps they’re complementary rather than contradictory – science revealing the how, spirituality the why.

Consider consciousness. Science maps neural activity, but only direct experience reveals what it feels like to see colour or feel love. Like wave-particle duality in quantum physics, apparent contradictions might signal we’re approaching something too fundamental for ordinary categories.

But even achieving theoretical integration leaves practical problems. How do we derive ethics from either science or spirituality? Science describes but doesn’t prescribe. Spirituality makes ethical claims based on experiences not everyone shares. We need ethics that can motivate action across different worldviews – whether you’re a materialist concerned for future generations or a mystic acting from experienced unity with life.

Environmental Ethics as Test Case

Our relationship with nature perfectly illustrates these challenges. If humans are just evolved animals, why care about other species beyond utility? Science can describe our ecological interdependence but can’t explain why it matters morally. Alternatively, if everything is sacred and interconnected, can we ever prioritise human needs? How do we balance individual freedom with collective survival?

Your ontology shapes your environmental ethics. Materialists might focus on sustainable resource management. Those believing consciousness is fundamental might emphasise intrinsic rights of all beings. Those experiencing the sacred might see destruction as desecration. Yet we need environmental action across all these worldviews. The planet can’t wait for philosophical consensus. Yet all forms of intelligence – cosmic, biological, symbolic – participate in regulatory patterns that sustain complex life.

Living with Paradox

Must worldviews be perfectly coherent to guide action? Perhaps not. Quantum physicists use wave-particle duality daily despite its paradox. We might similarly need to hold tensions without resolution. The key is distinguishing productive tensions that generate growth from destructive contradictions that paralyze action.

This requires provisional rather than dogmatic approaches – holding beliefs firmly enough to act but lightly enough to revise. When your actions don’t match your stated values, the question isn’t about achieving perfection but engaging consciously with tensions. Can you acknowledge where you fall short while working to close gaps? Can you recognise systemic constraints while taking responsibility?

Philosophy as Practice

Philosophy isn’t about reaching final answers but ongoing practice. Like musicians who never stop practicing scales, we must regularly audit our beliefs. Where have new experiences challenged assumptions? Where has new knowledge revealed errors? Where have changing circumstances made old frameworks obsolete?

This practice requires extraordinary willingness to revise cherished beliefs. We become attached to our worldviews – they provide identity, community, meaning. Revising them feels like death. Yet worldviews that cannot evolve become death-dealing rather than life-giving. Climate change alone demands fundamental revision of humanity’s self-understanding.

The practice is both individual and collective. We need personal coherence for effective action and collective frameworks for coordinated response. Your philosophical work matters not because you’ll achieve perfection but because worldview quality affects action quality. Every person who achieves greater coherence, who better aligns actions with values, who models integration of scientific and spiritual wisdom, contributes to possibilities for conscious systemic change.

This practice involves learning to participate consciously in the larger intelligence of which human thinking is one expression.

The Personal Challenge

What tensions exist in your own worldview? Where might you need philosophical work? How do you balance certainty sufficient for action with openness necessary for growth? We must act from incomplete understanding while remaining committed to improving that understanding. We must build the boat while sailing through a storm.

In our world of eight billion facing unprecedented challenges, we need leaders and citizens whose espoused values and embodied actions align. The incoherence between what leaders say and do undermines collective capacity for change. But waiting for perfect coherence means never acting. The invitation is to philosophical engagement, not perfection.

Emergency Navigation

Philosophy today is emergency navigation for a species attempting something without precedent: consciously influencing planetary-scale change before it’s imposed by collapse. The Great Oxidation Event transformed Earth’s atmosphere over millions of years through unconscious bacterial photosynthesis. We’re trying to transform civilisation in decades through conscious choice.

We’re one voice among billions, each trying to make sense of our moment. But paradigm shifts start with individuals who see anomalies others dismiss. The work isn’t about having final answers but improving questions, not achieving certainty but navigating uncertainty with wisdom.

This is philosophy as survival tool, as practice of hope – not hope that someone else will figure it out, but hope that collective wisdom can emerge from individual efforts at understanding. Not hope that we’ll get it perfectly right, but hope that we’ll get it right enough, soon enough, to navigate the narrow passage between collapse and transformation.

Terry Cooke-Davies — Written with the assistance of Claude (Anthropic AI)

14th September 2025