Introduction

Hardly a day goes by without some reference to “climate change”. It is changing the shape of politics in Western countries as “Green” parties take their place among political entities campaigning for our votes. It is changing the landscape of energy and transport markets as “renewables” eat into the share of fossil fuels, and electric cars become an increasingly common sight on our streets. Most significantly, it is changing the pattern of climate and weather, thereby triggering deep-seated changes to the relationship between humans and our home planet.

However, some people remain unconvinced that climate change is caused by human activity. After all, doubters point out, the climate has been constantly changing for billions of years – long before hominins of any kind emerged from the African savannah, let alone homo sapiens. Despite the increasingly gloomy reports from the Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the widely reported discussions of global leaders at the annual COP gatherings, why should we believe this time is any different from the countless prior changes in the Earth’s climate?

That is the question being investigated by the Anthropocene Working Group (AWG), an interdisciplinary research group dedicated to studying the Anthropocene as a geological time unit. It was established in 2009 as part of the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy (SQS), a constituent body of the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS). The ICS is charged with setting global standards for the fundamental scale for expressing the history of the Earth.

How Geology Helps Date the Earth’s History

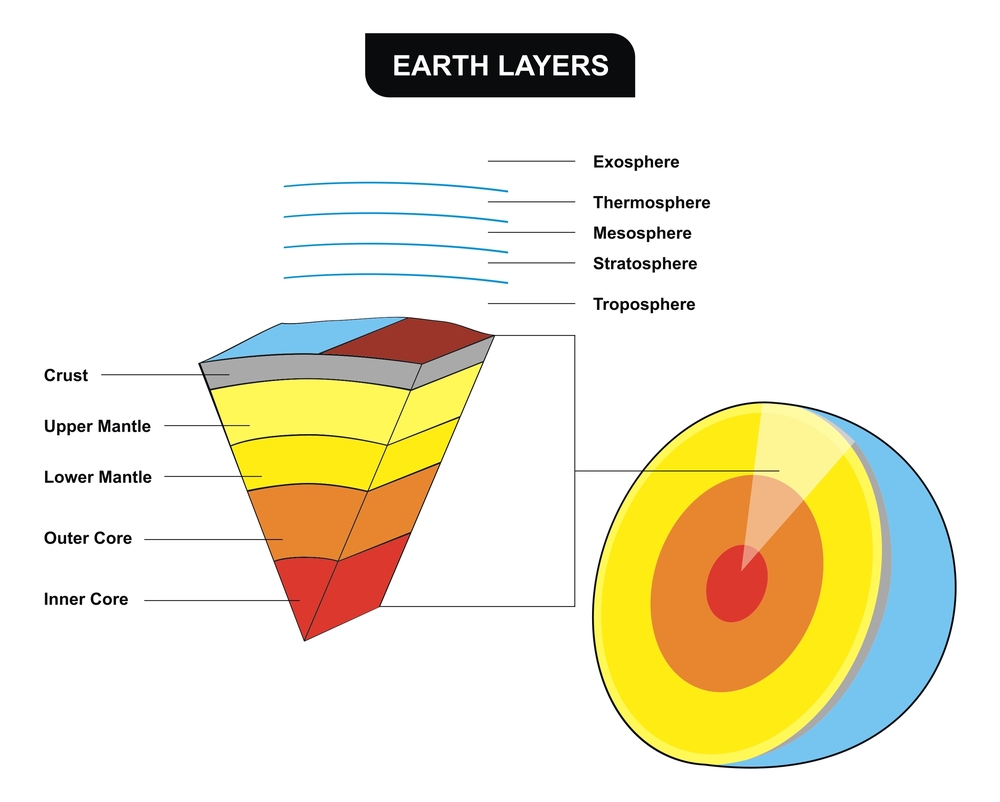

The ICS is a geological body, and the Anthropocene is proposed as the term to describe the most recent geological time unit in the history of the Earth. So, to understand its significance, it helps to understand something about the geological structure of the Earth.

The Earth has many layers, from a solid inner core, through layers of molten minerals in the outer core and the mantle, to a thin outer crust – the part of the Earth on which we live and where we make our home. If the Earth had the dimensions of a hard-boiled egg, the crust would be about the relative size of the eggshell.

Earth System Science

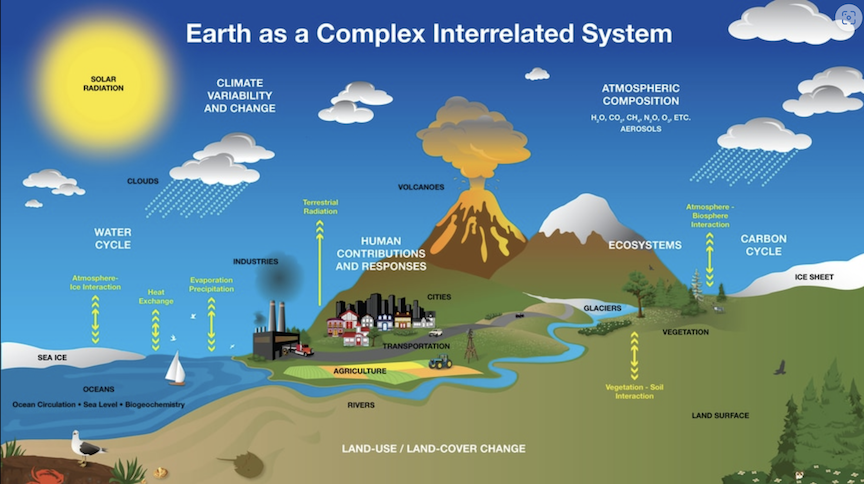

Life on Earth, as a whole, is referred to as the “biosphere” – the sum of all living creatures. The oceans, seas and rivers are referred to collectively as the “hydrosphere”, and the layer of gas above the Earth is known as the “atmosphere”. These layers are constantly in motion, and they have complex interactions with each other and, through volcanic activity, with the Earth’s mantle.

The study of how these different components of our home planet interact with each other, and, indeed, with the Sun, which provides all the energy required by the Earth to maintain life, is known as “Earth System Science”. The following diagram, showing many of these interactions, was produced by NASA’s Goddard Space Laboratory:

The biosphere, the hydrosphere, the atmosphere, and the mantle interact with the Earth’s crust to change its constituent rocks, which are divided into three basic types. Igneous rocks (such as basalt, granite or pumice) come from molten magma or the lava produced by volcanic eruptions. The accumulation of organic and mineral particles forms sedimentary rocks (such as limestone or sandstone). Limestone, for example, is produced by the shells of dead sea creatures that have sunk to the sea bed. Sandstone is similarly the accumulation of fine particles of soil or rock, dislodged by wind or water erosion and eventually compacted into rock. The third type of rock is “Metamorphic” rocks (such as marble or slate), which are existing rocks transformed through heat and pressure.

Stratigraphy and Dating

Among the first to recognise the significance of rock layers (or strata) for dating was an English surveyor for canals and coal mines, William Smith, who, in 1815, published the first stratigraphic map of the UK. (See illustration below).

As he cut trenches through the Earth for canals and mines, he noticed that there were sequences of rock layers that appeared in the same order in different parts of the country. Since different strata contain different types of fossils, it is possible to tell the age of a stratum by the stage of evolution of the various creatures fossilised within it.

Nowadays, of course, dating strata by fossils (biostratigraphy) has been supplemented by other methods such as radio-carbon dating (radiostratigraphy) or identifying the degree and direction of the magnetic field enclosed by the rocks (magnetostratigraphy).

The ICS, to which we were introduced very early in this article, was founded in 1961 and is the body responsible for the integrity of dating the Earth’s stratigraphic age. It is they who set up the AWG. The current chart of the different periods of the Earth, the formidable named “International Chronostratigraphic Chart”, can be viewed at ChronostratChart2023-09 (www.stratigraphy.org)

The Anthropocene

The term “Anthropocene” was coined by the Nobel Laureate Paul Crutzen and Eugene Stoermer in 2000 to denote the present geological time interval, in which many conditions and processes on Earth are profoundly altered by human impact. This impact has intensified significantly since the onset of industrialisation, taking us out of the Earth System state typical of the Holocene Epoch that post-dates the last glaciation.

As the AWG states on its website, “Phenomena associated with the Anthropocene include: an order-of-magnitude increase in erosion and sediment transport associated with urbanisation and agriculture; marked and abrupt anthropogenic perturbations of the cycles of elements such as carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus and various metals together with new chemical compounds; environmental changes generated by these perturbations, including global warming, sea-level rise, ocean acidification and spreading oceanic ‘dead zones’; rapid changes in the biosphere both on land and in the sea, as a result of habitat loss, predation, explosion of domestic animal populations and species invasions; and the proliferation and global dispersion of many new ‘minerals’ and ‘rocks’ including concrete, fly ash and plastics, and the myriad ‘technofossils’ produced from these and other materials.”

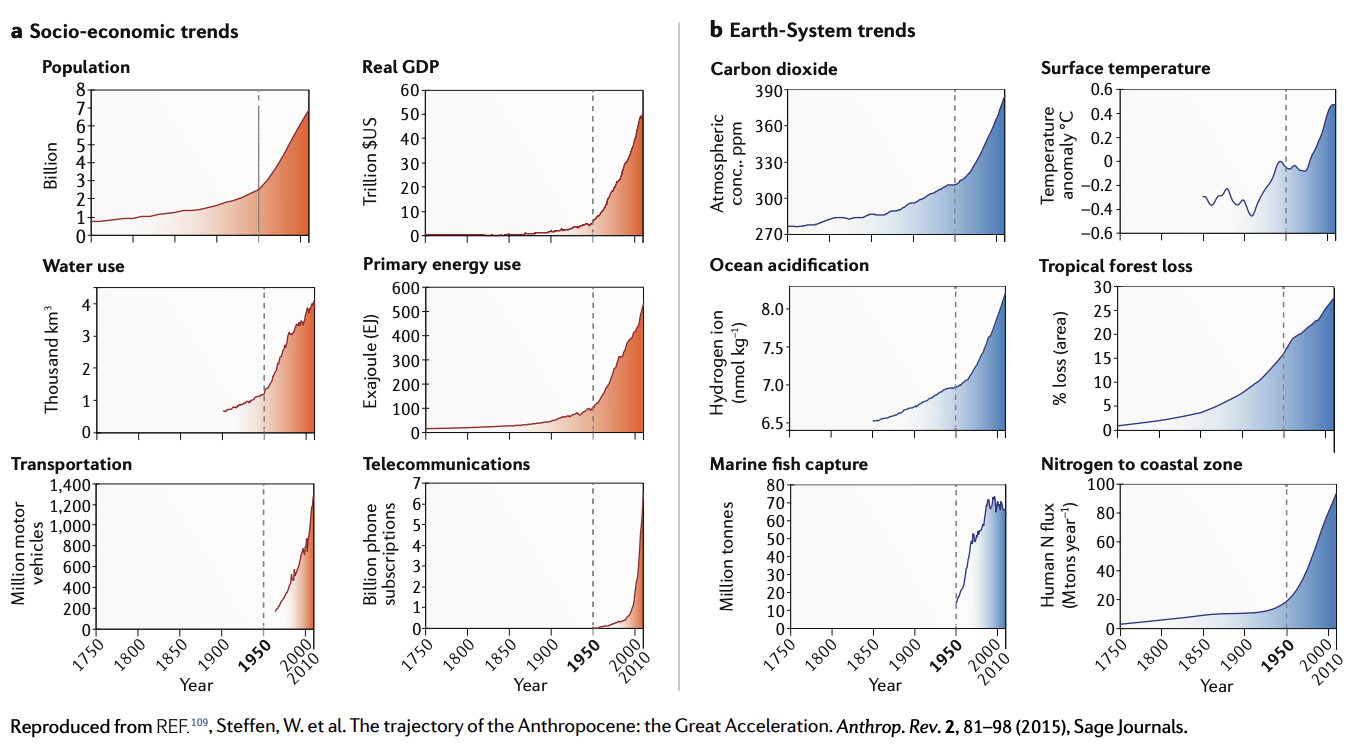

One member of the AWG, William Steffen, in particular, has been prolific in investigating and publishing results supporting the group’s proposal. He has produced charts pointing to a “great acceleration” in human activities across various measures, showing that those correspond with similar increases in Earth-system trends. (See chart below)

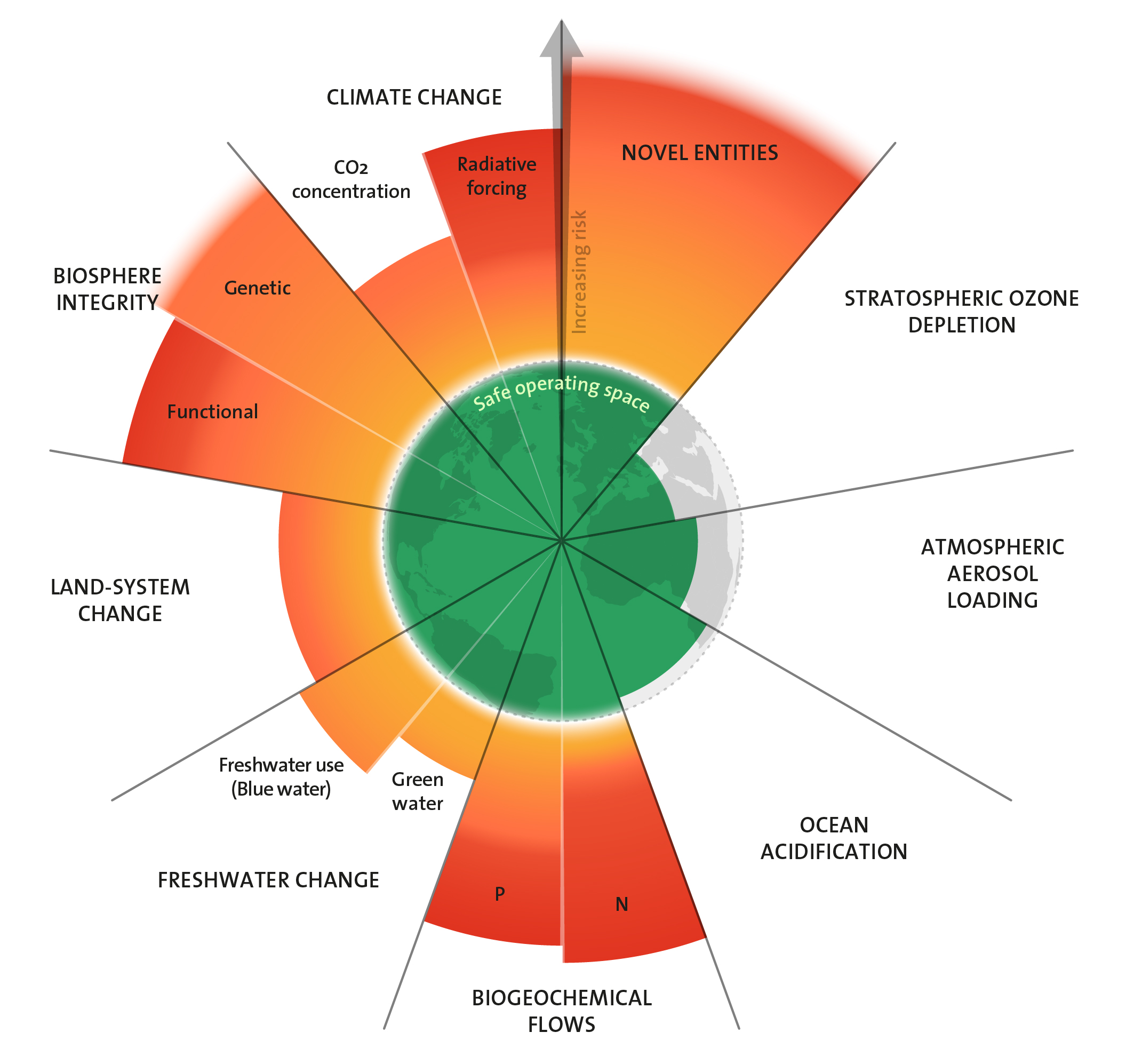

He was also a strong supporter of the work of a team of scientists who proposed a set of nine “planetary boundaries” within which humanity can continue to develop and thrive for generations to come. These boundaries regulate the stability and resilience of the Earth system in much the same ways as blood pressure, pulse rate, body temperature and so on control the health of a person. Their state in September 2023 is shown in the diagram below:

Humanity’s “Grand Challenges”

In their book, “The Anthropocene”, three members of the AWG write. “The Anthropocene presents not a problem, but a predicament. … A problem may be solved … by experts …, but a predicament presents a challenging situation requiring resources of many kinds. We don’t solve predicaments; instead, we persevere with more or less grace and decency.” Indeed, a “predicament” is a term that I started using in 2019 when I first started to think and write about the impact we humans have on our planet.

Many of the academic papers that I have read on the constituent parts of this predicament, however, do not use that term but instead refer to them as “grand challenges”. And there are many of them. The following list needs to be completed, but it represents those that came to mind while preparing this article. The categorisation is simply for convenience.

Environmental Degradation

- Biodiversity Loss: Extinction rates are soaring, which could lead to ecological imbalances.

- Deforestation: Loss of forests impacts biodiversity, carbon sequestration, and indigenous communities.

- Climate Change: Rising temperatures, extreme weather, sea-level rise, and increased frequency of natural disasters.

- Pollution: Chemicals and plastics affecting terrestrial and marine ecosystems.

- Ocean Acidification: This affects marine ecosystems and is particularly harmful to coral reefs and shellfish.

Resource Scarcity

- Water Scarcity: Access to clean water is increasingly becoming a global issue.

- Food Security: The need for more efficient, equitable, and sustainable food systems.

- Non-Renewable Resources: Over-reliance on fossil fuels and minerals.

Social Challenges

- Inequality: Wealth and income disparities within and between countries.

- Global Health: Pandemics, antibiotic resistance, and healthcare availability.

- Migration and Refugees: Caused by conflict, environmental degradation, and economic hardship.

Governance and Systems

- Global Governance: Managing global commons, law, and security.

- Sustainable Development: Balancing growth with environmental and social well-being.

- Technology and Ethics: Issues surrounding data privacy, AI, and biotechnology.

Knowledge and Information

- Education: Access to quality education and information.

- Misinformation: The spread of false or misleading information, often through social media.

Learning from the Past

During the past twelve months, a group in Shepway and District u3a have reflected on a dozen topics from the history of Western Thought relevant to our present predicament. We have considered how insights from science, philosophy, and spirituality have all played their part in bringing us to our current predicament.

In his 1905 book, “The Life of Reason”, the Spanish-born American author, philosopher and poet George Santayana wrote, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”, and so I have tried to reflect on each of the twelve topics we considered, and pose some questions suggested by our intellectual odyssey.

Stories and Perception

- Our stories shape how we perceive the world. What stories are we telling ourselves about the state of the world today?

Journey of the universe

- What will we tell our grandchildren about where we came from and what we are doing here?

Geography of Thought

- Does reality primarily consist of change and relationships? Or objects and characteristics?

Christendom

- What does Christianity have to offer us, both in today’s world, and as a legacy?

- To what extent are we, in the West, still governed by the principles of Roman law?

Roots of Science

- Do other cultures see and value different things from us?

- What can we learn about individual freedom versus shared needs from indigenous people?

- Did the Copernican Revolution make our species and planet seem so “insignificant” that it encouraged us to ditch all feelings of “awe” towards our world and ourselves?

Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment

- To what extent do we still embrace a “mechanistic” attitude to the world, and how does that influence our actions?

- Has the pendulum swung too far towards “individual rights and freedom” at the expense of “the common good”?

- Did the impulse to secularisation result in the importance of morality, ethics, aesthetics and spirituality being scrapped along with church domination and corruption?

- Did the Enlightenment sow the seeds of “unbridled capitalism” and nation-states less powerful than global corporations and the “mega-rich”?

The Theory of Evolution and the Modern Synthesis

- Do we misunderstand evolution as “progress”, with humans somehow at the “pinnacle” of the natural process of evolution?

- Does seeing humankind as simply another animal reinforce the feeling of insignificance begun by the Copernican Revolution?

Science and the World’s Faiths

- Does the entanglement of science and religion tend to undermine the spiritual experiences that can be gained with groups of fellow believers?

- Is it fair to blame religion for some of the world’s most prolonged and recalcitrant conflicts?

The Embodied Mind

- Does this new understanding of the human condition that recognises the embodiment of our minds change how we think about “life together’, which has broadly remained the same since the Enlightenment?

- Do the enlightenment values of “Liberty, Fraternity, and Equality” still stand up in the face of what we have subsequently learned about the human condition?

Artificial Intelligence

- Does AI add new “Grand Challenges” to the growing list of threats to humanity’s well-being, or does it herald new prosperity and additional tools to help us live sustainably and at peace with the Earth?

- Is the modern post-enlightenment world order capable of containing the threats from AI?

Scientific Naturalism

- Does our ethical maturity and current world order provide us with the governance capability to use our technological power over “nature” wisely?

The Anthropocene and Humanity’s Grand Challenges

- Should we be talking about “the Anthropocene”? If so, what difference does it make?

- Can humanity as a whole work together for the common good? If so, how? If not – what then?

Conclusion

In his 1965 book “The Art of Judgement”, Sir Geoffrey Vickers described human history as a “two stranded rope: the history of events and the history of ideas [which] develop in intimate relation with each other yet each according to its own logic and its own timescale; and each conditions both its own future and the future of the other.” If the AWG’s proposals are correct, are these two strands also conditioning the Human Planet’s future?

Terry Cooke-Davies

5th November 2023.

Image Credits:

Header: Created by Midjourney

Earth’s Layers: Shutterstock

Earth as Complex System – NASA’s Goddard Space Laboratory.

1815 Stratigraphic Map of UK: museumwales.ac.uk

The Great Acceleration: Steffen, W. et. al. The trajectory of the Anthropocene: The Great Acceleration. Anthrop. Rev. 2 81-98 (2015)

Planetary Boundaries: Licenced under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0. Credit: Azote for Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University. Based on Richardson et al. 2023, Steffen et al. 2015, and Rockström et al. 2009