Stories are everywhere

How many stories does the average person consume in a day?

It’s not an easy question to answer. When I recently googled it I got 5,270 million hits. But when I looked through them, not one was relevant until I reached almost the bottom of the third page. Plenty of precise answers about calories (2,000 or 3,000 depending on age, gender, activity etc.), liquid (3.7 litres for men and 2.7 litres for women), or even air (11,000 litres – rather surprisingly specific). But very little that even hinted at the number of stories.

Which is surprising. Admittedly we don’t consume stories like we breathe air – non-stop twenty-four hours each day. But I imagine that most of us spend more time telling, reading, watching or listening to stories (of one sort or another) than we do eating or drinking. Stories come in all shapes and sizes. Books and magazines, news stories, theatre, movies, TV dramas, social media, or anecdotes told by colleagues or friends. Stories even have a recognisable structure that is taught to primary school children. It is true to say that stories are all around us.

But if they are all around us, they are also intimately tied up with who we are. As a species, we have a uniquely long childhood. We spend our first few years sorting out how we get along with other people as social actors. By the time we are five or six years old, we start to add the role of motivated agent, working out how we can get what we want from other people and the world around us. Later still, in our teenage years, we start to tell ourselves stories about who we are and how we fit into the world. By the time we become young adults, we are fully-paid up authors of our autobiographies. We may never write our life story down or even rehearse it to ourselves as a coherent narrative, but our personality is shaped by it. As we experience life’s triumphs and disasters, it helps us to maintain our identity.

Stories are also the glue that binds groups of people together. We hear the cultural tales of our family, nation, and school, which teach us our values. We hear the stories of our culture’s heroes and heroines, and they become aspirational role models for us. We hear our religion’s or tradition’s foundational myths, which teach us what our lives mean. These stories may or may not have a basis in actual events. But there is another class of ‘shared story’ that binds us together and creates the foundation for our experience of the world.

We live in twin realities

Around two thousand seven hundred years ago, something momentous began to happen in China and the Greek cities of the eastern Aegean. Before then, people in many parts of the world had used various materials to facilitate the exchange of goods or as a medium of payment. The materials included animal hides, cowrie shells and precious metals. But the innovation was to stamp metal coins in specific shapes with two particular pieces of information on them: a numeric equivalent value and the issuing authority. This allowed the coin to represent the abstract concept of a specific ‘value’ independently of the metal object itself. Money, a concept invented by humans, became a fiction shared by people worldwide and printed on pieces of paper or plastic.

And money, (or GDP as it is reported in news stories), is now the way that every nation measures its power in the world. It is just one of the many abstractions that enable the modern world to function. Concepts such as ‘the law’ allow two lawyers from different countries to co-operate in defending a third individual whom neither has met. The badge on the bonnet of your car identifies it as manufactured by Ford, BMW or Tesla. However, these prominent corporations are also fictitious entities. They exist only in the collective imaginations of human beings. Lawyers refer to them as ‘legal fictions.’

Shared fictions play such an essential part in our lives that humans live in twin realities. On the one hand, the reality of the physical world of mountains, rivers, trees and horses; and on the other, the imagined reality of nations, corporations, laws and money.

We each have a unique perspective on the world.

Every day, we are exposed to all three types of story: public, autobiographical, and ‘shared fictions’. The particular mix we choose to engage with makes up our unique ‘worldview’, which acts as the lens through which we perceive the world. Not only the imagined reality but also the physical one. You could say that our worldview creates the windows through which we see the world – except that it involves all of our senses and not just sight.

And there is something that we should know about our senses. They do not operate like scientific instruments. Our eyes are not like windows or cameras. Our ears are not microphones. Our noses are not gas chromatographs. They are not passive devices that accurately represent what is there. The following pictures, which you might be familiar with, illustrate what I mean.

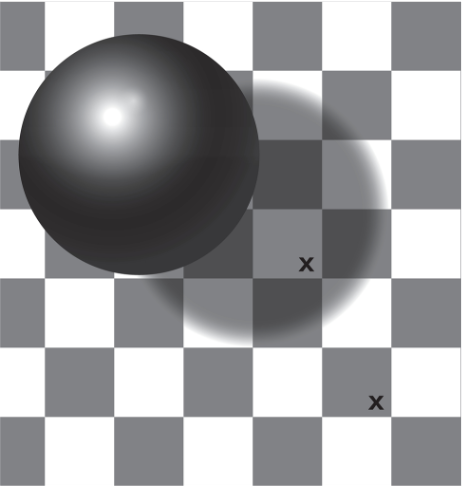

In the picture above, two squares are marked ‘x’. Do they look the same shade of grey as each other? Or is one lighter and one darker?

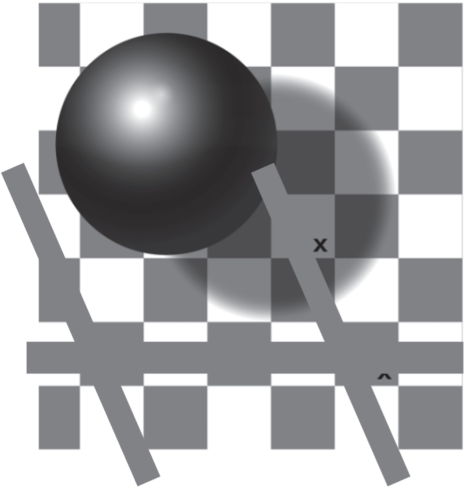

As the second picture shows, they are both the same shade of grey. But that isn’t how we see them. The picture looks like a sphere on top of a checkerboard and casting a shadow. We know that checkerboards have alternating light and dark squares, so we see the upper of the two marked squares as a light one in the sphere’s shadow.

And this isn’t a ‘mistake’ or a ‘bug’ that evolution has somehow been allowed to creep into the software running our optic nerve or brain cells.

Our interpretive brain

Our brain, the “master controller” of our central nervous system, has one job – to keep us alive. And it does that through anticipating what might threaten our existence, both in the world around us and inside our bodies. It continually monitors ‘what is out there’ and ‘what is going on in here’. Most of what it does is outside of our awareness. For example, at this very moment, your brain is making myriad adjustments to maintain your body’s temperature at precisely the value it needs for optimum well-being, regardless of whether you are in a room at -5oC or +30oC. And I don’t suppose you are consciously aware of what it is doing or how it is doing it.

And that makes sense. The brain is energy-hungry. It accounts for only 2% of body weight but consumes approximately 20% of available energy (glucose and oxygen). The hungriest part of the brain is the neo-cortex, the region that generates our consciousness. And it uses the most energy and takes the longest time to compute.

So, outside our awareness, the brain processes our sensory inputs and presents to our consciousness what we need if we are to make sense of what is really ‘out there’ – i.e. in this case, a checkerboard with a sphere on it, casting a shadow. This enables us to react appropriately without using time and energy to analyse each square’s specific shades of grey.

The ‘quirks’ of our senses are features, not bugs. And they have allowed homo sapiens to dominate our world and change it in ways no other species has ever been able to.

Victims of our success

We are a social species, and our world of stories has allowed us to co-operate in large groups: families, clans, nations and even empires. We have an astounding ability to focus attention on a common goal using mass communication. As a result, the scientific revolution has allowed humans worldwide to make undreamt-of discoveries and develop powerful technologies. The industrial revolution has allowed us to apply these technologies to expand life expectancy, reduce disease and raise living standards to heights unimaginable to our ancestors.

But there is a shadow side to this successful formula of extensive group cooperation. Our tribal nature has allowed millions of people passionately to embrace a shared national, racial or religious identity. But it seems that this same nature will not permit an “us” to exist without simultaneously creating a “them”.

And this matters because we, as a species, have helped to create a situation where our collective behaviour is jeopardising the well-being of tens of thousands of different species, possibly including our own. Collectively, the combined impact of our population, technology and industry are playing havoc with the ecosystems that maintain our planet as the cradle of life. Climate change, biodiversity loss, habitat loss, pollution, ocean acidification, and burgeoning inequality are not separate problems. They are all systemically related.

We couldn’t have foreseen this. We are the victims of our success. We are dealing with the unforeseen consequences of doing what we are good at. No single nation, race or religion is responsible for our dilemma. But neither can any single country, race, or religion take the steps necessary to restore the earth’s health.

It is our shared predicament, but the shadow side of our sociality has hindered every attempt to agree on what we should do about it.

Learn to see beyond our perspective

It’s easy to feel helpless in the face of such a challenge. Particularly when we think about the state of the world our descendants will inherit from us. And my perception is limited and prejudiced, just as everyone else’s is.

But there are several things we can do to help us become conscious agents for improvement instead of unthinking contributors to the predicament. Here are three that I have found helpful.

Firstly, hold on to the notion that there is such a thing as a shared reality. There are some things that every sane human ought to be able to agree on: bullets kill, water flows downhill, and the sun rises in the east, for example. Don’t let the welter of ‘fake news’ stories and talk of ‘post-truth’ persuade you that there is no such thing as a shared reality.

Secondly, take what I have said about stories and worldviews to heart. It’s an extension of something my friend and colleague Vince Nolan once told me: “When you think you are arguing with an idiot – so do they.” Recognise that we all have our worldviews, some of which will certainly be wrong, so try to understand what they can see that you can’t. I found Edgar Schein’s book, “Humble Enquiry” an excellent resource.

Finally, reflect on the stories that help make up your worldview. Are they helping you to make the kind of changes you would like to see? Or are they limiting you and holding you back? If they are not helping, change them. We humans are, after all, story-telling animals.