“Sapiens” – 1) rational; 2) sane, of sound mind; 3) wise, judicious, understanding; 4) discreet. (Online Latin Dictionary)

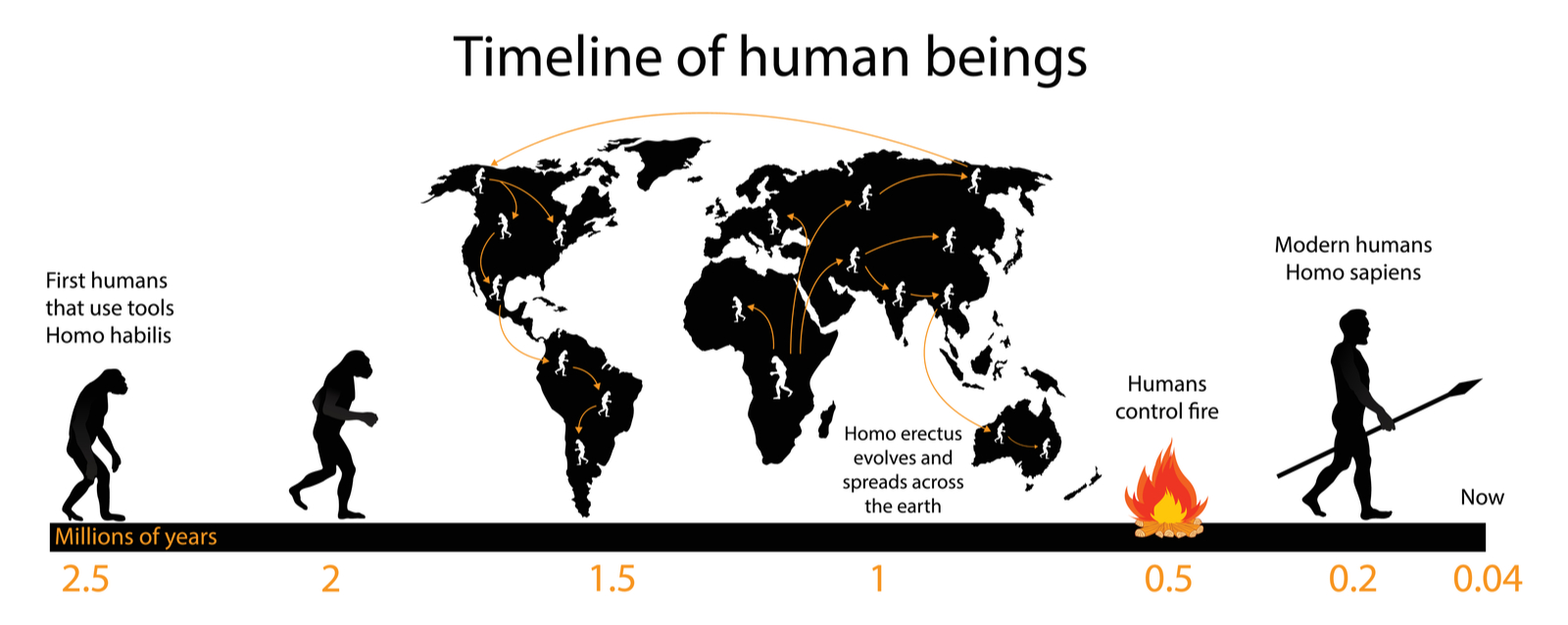

Homo sapiens, (Latin: “wise man”) the species to which all modern human beings belong. Homo sapiens is one of several species grouped into the genus Homo, but it is the only one that is not extinct. (Britannica.com)

Do we humans behave as if we are ‘wise’?

As a species we have referred to ourselves as homo sapiens since1758, when the name was applied by the father of modern biological classification, Carolus Linnaeus. But a glance at the current state of the world suggests that we aren’t entirely living up to the ‘wise’ part of it.

We have certainly accomplished many great advances in both the Arts and the Sciences. Think of wonders such as the Taj Mahal, or the International Space Station, or the Internet and computer technology, which is allowing you to read this now. The list is extensive and awe-inspiring, as books like Charles Murray’s ‘Human Accomplishment’ set out so clearly.

But our accomplishments are only a part of the story. A moment’s reflection on the twentieth century with its well-documented world wars, genocides and other crimes against humanity shows that we are individually and collectively capable of behaviour that is the very opposite of rational, sane, judicious or discreet.

And right now, twenty percent of the way through the twenty first century, it seems to me that we need to seriously raise our game both individually and collectively if we are to rise to the numerous crises and challenges that confront us today. It is bad enough that our inability to live together in harmony with our fellow human beings shows up in such varied ways as international tensions, growing polarisation over social issues, endemic terrorism, the humanitarian disaster of refugees and forced migrations, and persistent social injustice. But now centuries of exploiting natural resources, both living and inanimate, is confronting all the inhabitants of our planet including ourselves with such consequences as climate change, biodiversity loss, pollution, and habitat loss. The current coronavirus pandemic reminds us of the folly of imagining ourselves to be independent of the vast web of life and interlocked ecology of our unique planet.

We know that we are capable of rising to the challenge. Our awe-inspiring accomplishments tell us we can. And so do the many small acts of individual kindness and heroism that we know about in our own communities. In the global struggle to save lives and reduce suffering from the current pandemic, we have never seen such rapid growth in specialist knowledge about the virus. We are learning about the medical science faster than ever before.

But there’s the rub! Our advances in scientific knowledge don’t seem to be matched by advances in social knowledge. Governments around the world are failing to win support from their people, and individuals foolishly and recklessly ignore the impact of their own behaviour on others.

In Search of Wisdom

Wisdom of course is constrained by knowledge; both ‘know what’ and ‘know how’. And as the world has become more and more complex, no one person has access to more than a fraction of what is known. Even as individuals, we tend to compartmentalise our knowledge, and don’t always ‘join the dots’. Sometimes because it suits us, and sometimes because we just don’t see the connections.

Against this background while learning to come to terms with a newly-enforced lockdown, I found myself in April in conversation with a friend and colleague, Dr Mark Winter of the Alliance Manchester Business School. We were discussing how to curate large bodies of material (Mark’s much larger than mine) that we had each created in the course of our studies, our teaching material and our research.

In my case I was also motivated by a long-standing personal desire to ‘join the dots’ of snippets and insights that I had gathered from different fields of knowledge that I have been interested in throughout my life: what we know about what it means to be human; how to manage people in organizations and projects; and how to reconcile Christianity with advances in scientific knowledge.

The outcome of all this has been this web site which hosts this post – www.insearchofwisdom.online. It brings together knowledge from many different disciplines, and my intention is to add to it continually. It currently references nearly two hundred books as well as some research papers, articles, bible studies and sermons that I have written myself. Eventually it is intended to have more than twice that number of books, as well as more blog posts, articles and studies.

You can see how it works in the remainder of this article. In it, I have chosen just twenty-five books that have each left their mark on my thinking. Each, in its own way, offers insights that seem to me to be relevant to the crises that we face as human beings today. If you click on the title of any of them, you will see a short extract from the book’s cover, and if the book is available in Kindle form, you will also be able to link to the ‘Goodreads’ sample from the beginning of the book. Interactive links will also lead you to material that relates to the same subject, or to topical issues to which the book makes a contribution.

Searching for Wisdom in Twenty-Five Books.

A personal inter-disciplinary exploration of a small section of the world’s insights. Click on any book title to take you to an extract, from which you can click to read firther, or click on any of the interactive links to related perpectives, subjects or issues.

How we came to dominate the earth.

An interesting place to start the search for wisdom, is by understanding what is now known about how homo sapiens came to occupy our present position in the ecology of our plant. Journey of the Universe (1) tells the story of how we came to exist as we do today right from the ‘Big Bang’ 13.8 billion years or so ago. It is supported by an Emmy Award-winning film, and a series of online courses provided by Yale University. A somewhat different take on the evolution of life on our planet is told by the eminent scientist Edward O. Wilson in The Social Conquest of Earth (2), and the entire sweep of human history is brilliantly surveyed in Yuval Harari’s brilliant Sapiens (3)

What we are doing with our dominance

Jared Diamond’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Guns, Germs and Steel (4) shows how the modern Western World achieved its predominant economic situation, while The Great Imperial Hangover (5) examines the lasting impact on modern life of the great empires – the chosen social structure by which, among other things, we distribute resources among the nations. How our over-use of these resources leads not only to climate change, but also to many of our other current challenges are laid bare in Overshoot (6), and the consequences for us are starkly set out in Mike Berners-Lee’s There is no Planet B (7).

What we have learned about human nature

Modern science has revealed much about how we humans differ in both physical and cognitive terms from our fellow inhabitants of earth, and these are superbly summarised in The Gap (8). The idiosyncrasies of our habits of thought, both conscious and sub-conscious are brilliantly set out by the Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman in Thinking, Fast and Slow (9). How this impacts our social relations and sense of identity is examined comprehensively and insightfully in Us and Them (10), while the effect it has on our cultural and social values is dissected in Moral Tribes (11).

Hidden dimensions of our world

Scientists dealing with complexity at both very large scale (cosmology) and very small (quantum mechanics) have discovered some surprising facts about the world that seemed so stable during the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. In The End of Certainty (12), Nobel Laureate Ilya Prigogine reveals the unpredictability inherent in the structure of the universe. NASA, in the meantime, has published Cosmos and Culture (13), a collection of essays by eminent scientists in various disciplines that identifies the accelerating pace by which the Universe is evolving first through physical evolution, then with the emergence of life through biological evolution and now, with the widespread dominance of homo sapiens, through cultural evolution.

Understanding some less obvious characteristics of organizations

Managers of business and commercial organizations tend, of necessity, to be practical people, and there are many helpful books and magazines aimed at this market. In my experience, however, there is a deeply-rooted tendency to treat abstract and artificial entities (such as projects or organizational hierarches) as if they were simply another form of natural object, and subject to similar laws. Herbert Simon drew attention to the problems that this creates in The Sciences of the Artificial (14). The work of psychologists like Daniel Kahneman gave rise to the study of ‘behavioural economics’, penetratingly and amusingly described in Freakonomics (15), which lays bare the hidden forces that motivate organizational behaviour. Other aspects of organizational culture that often lie hidden from conscious awareness are explored in The Paradox of Control in Organizations (16). My favourite book on the techniques that can help to reveal these characteristics is Edgar Schein’s brilliant Humble Inquiry (17) which should, in my opinion, be required reading for anyone in a management or leadership position in any organization.

Reconciling faith with science

Ever since I studied both Electrical Engineering and subsequently Christian Theology at University in the early 1960s, I have been faced with the challenge of reconciling the wisdom revealed in the Bible and the Jewish and Christian traditions with the rapidly-expanding evidence-based knowledge generated by science. I have found many books helpful, but three stand out for having provided me with rational ways to understand how the two fit together in mutually complementary ways. Peter Enns’ How the Bible Actually Works (18) provides surprising insights into the relevance of the ancient documents contained in the Bible to the people for whom they were originally written. In Evolution of the Word (19) an eminent New Testament scholar publishes the books of the New Testament in the sequence that they were probably written in, which provides a fascinating insight into the development of doctrine within the early church. Approaching the topic from a completely different angle, Thank God for Evolution (20) presents a persuasive case for the complementary roles of science and religion in the development of wisdom.

Recognition of the social consequences of Empire as the way humanity controls access to its resources has led to a field of study that demonstrated the subversive counter-cultural nature of the Jewish and Christian faiths. In the Shadow of Empire (21) traces the Biblical resistance to Empire over the millennium or so of the Bible’s creation, while Unveiling Empire (22) dissects the last book in the Bible, the Book of Revelation, showing how strongly the text reveals the subversive nature of the earliest Christian communities.

Living Wisely

We have already said that wisdom is constrained by knowledge. But wisdom involves more than what we know – it also involves what we do with what we know. Each of the final three books that I have chosen encourages us individually and collectively to wise and considered action.

Postcards from Babylon (23) is an unashamedly Christian book that provides a wake-up call to practicing Christians (particularly in the West) to be aware of and resist the Empire-like promises of our modern-day national and commercial world, which end up having such devastating consequences, not only for humanity, but for the entire earth community. Life at the End of Us vs Them (24) describes a series of real-life case studies that demonstrate how deeply “us versus them” is embedded into every aspect of our social lives, and how hard it is to deflect its harmful consequences. Finally Natural Born Learners (25) claims that one of homo sapiens’ most prominent characteristics is our adaptability and our commitment to life-long learning, and offers many examples of how we can adapt our educational systems to encourage this characteristic as the best hope we have of overcoming the challenges we face.

Please join me on this quest

If anything that you have read in this post strikes chords with you, I would love to hear from you.. I would welcome suggestions for books to include on the site, topics to explore, or comments on how to improve the web site, as well as responses to this particular post. I am well aware of how precious your time is, so thank you for taking the time to read this post. I hope it will have been worth it.