Introduction

This is not an essay about saving the world. It’s about learning to live inside its compost pile.

We are conditioned to think that if something is breaking, the only responsible thing to do is fix it—or, failing that, replace it. But some things are not meant to be restored. Some are meant to rot, to return to the dark metabolism that makes all new life possible. Modernity has taught us to fear that darkness, to see it as failure, loss, or waste. In the forest, it is none of these.

Here, the contemplative tradition’s whisper—everything is already whole—and science’s insistence—everything is in motion—are not opposites but twin truths. They dissolve the illusion that we must choose between resting in completeness and engaging in transformation. Wholeness holds the wound; the wound is part of the wholeness.

The pages that follow are not a blueprint for what comes next. They are an invitation to step into the messy, necessary work of decomposition—not as a retreat from responsibility, but as its truest form. If trees can seal a wound without seeking revenge, if fungal threads can turn the body of what was into the nourishment for what will be, then perhaps we, too, can learn to participate in this ongoing metabolism.

If you enter here, leave behind the hope of finishing the work. What waits beyond this threshold is not resolution, but the chance to become part of life’s unending repair.

The Body

The imagined boundary between sacred and secular dissolves when we see that completeness and change are not opposites but two currents of the same river. Contemplative traditions tell us, everything is already whole. Science affirms, everything is in motion. These are not competing claims but parallel ways of listening to the same relational field—the same heartbeat, one chamber resting, the other pumping.

From here, the modernist dilemma—whether to fix the world or rest in its perfection—loses its grip. Wholeness holds the wound, and the wound calls us deeper into wholeness. The completeness of life does not absolve us from responsibility; it is the very ground from which responsibility grows.

Yet much of what passes for “meaningful work” today operates like Bauman’s cyber-mole—burning energy in the search for energy, sustaining dying systems by endlessly recharging their batteries. Corporate sustainability plans that extract to offset extraction. Conferences that fly thousands of people to discuss reducing flights. Regulations that tangle themselves in bureaucracy while the harm continues. The question is not only how to work, but what kind of metabolism our work serves.

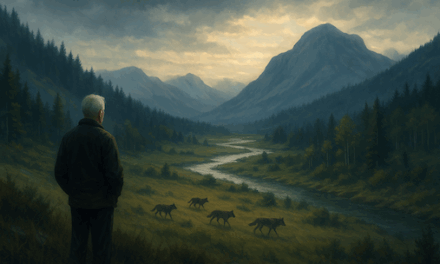

The sacred does not hover above the material world; it moves through it—threading itself into the mycelial exchanges underfoot, the river’s patience in carving stone, the way trees seal their wounds while continuing to grow. In the forest, a fallen Douglas fir is not waste to be cleared, but an entry into the detrital food web—fungi, bacteria, invertebrates, all transforming the body of what was into the nutrients for what will be. Trees don’t seek revenge; they practice constant repair, adapting to what comes, staying vigilant without bitterness.

We, too, can become skilled decomposers of our cultural moment. Each generation brings gifts to this work: the memory of systems before acceleration, the early questioning of infinite growth, the systems-thinking born of instability, the intuitive refusal to prop up what is no longer viable. Together, these gifts can support composting competencies—relational, spiritual, and practical skills for navigating endings and beginnings.

This is not a call to romanticise collapse or abandon all institutions. It is an invitation to learn the art of distinguishing between what serves life and what merely consumes energy. Sometimes this will mean hospicing dying institutions while midwifing new forms; sometimes it will mean retiring what no longer serves and tending spaces for emergence without rushing to scale. It will mean cultivating practices of repair that are constant but never finished.

To participate in this ongoing metabolism is to refuse both the illusion of a final solution and the temptation to disengage because the work will not end. It is to live as part of the larger intelligence that holds galaxies in their spirals and forests in their quiet flourishing—where being and becoming are simply two faces of the same truth.

Closing

The forest does not mistake the nurse log for failure. It knows that endings, tended well, are simply the beginning in another register. The same can be true for us—if we can bear to stand inside the compost pile long enough to let it work on us, and to work with it.

Wholeness holds the wound. The wound keeps us honest. The repair is never finished.

Terry Cooke-Davies

15th August 2025

With assistance from the GTDF Collective’s Braider Tumbleweed II and Anthropic AI’s Claude.