We often hear freedom described as a universal right, something everyone is entitled to. “Only in a democratic environment can one be free,” writes David Cigoj in New World Philosophy for You. “Human rights guarantee freedom.” It sounds convincing, doesn’t it? Yet, like many grand statements, this one raises more questions than it answers. What does freedom actually mean? Is it something we can guarantee to all people universally? And how do human rights play into this?

Exploring these questions means unpacking different ways of thinking about freedom, including some that may challenge our usual assumptions. It turns out, the concept of freedom isn’t as straightforward as it might seem. Let’s look at some historical, philosophical, and cultural perspectives to shed light on what freedom means—and what it doesn’t mean.

Freedom and Its Constraints: A Matter of Context

When we talk about freedom, we often imagine it as something absolute, something that lets us do whatever we want. But is that really possible? A helpful metaphor comes from the philosopher Friedrich Schelling, who described life as whirlpools in a stream. Just as water forms temporary patterns within a river, so too do we live within the currents of history, society, and biology. Our choices and movements are shaped by forces beyond our control and our past actions, limiting what we can actually do in the present moment.

Similarly, the image of a “moving finger”, immortalised in the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, reminds us that the flow of history and the constraints of our environment are constantly shaping our lives. Freedom, in this view, is less about being able to do anything we please and more about finding room to manoeuvre within the currents of the world around us. It’s a more constrained, dynamic view of freedom—one that acknowledges how much our circumstances shape us.

Cultural Roots of Freedom: Different Societies, Different Ideas

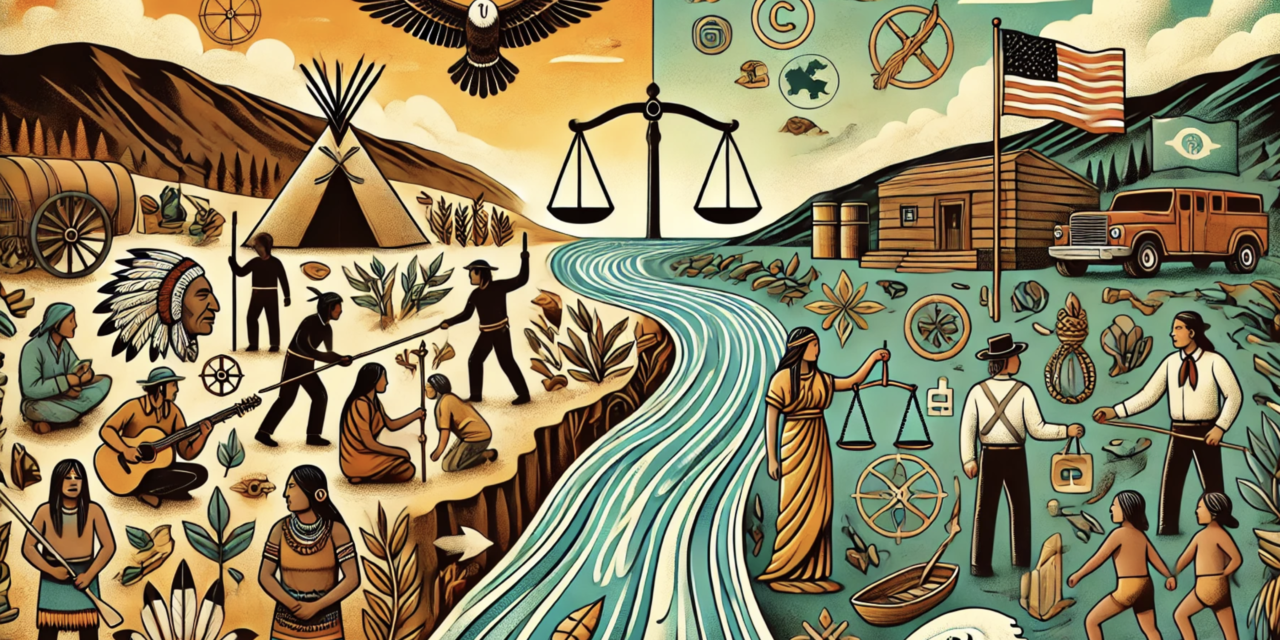

When we dig into history, it becomes clear that not all societies have understood freedom in the same way. Consider the Indigenous societies that anthropologists David Graeber and David Wengrow describe in The Dawn of Everything. In these communities, freedom was about communal support and “baseline communism”—ensuring everyone’s basic needs were met so that individuals weren’t forced to make desperate choices just to survive. Freedom here wasn’t about autonomy or independence; it was about interdependence, with community members supporting each other to create a stable foundation for everyone’s well-being.

Contrast this with the European view that developed over centuries, especially in the context of Roman law. In Rome, freedom was closely tied to property rights. The male head of a household had absolute control over his possessions, including his family and slaves. Freedom was about self-sufficiency and autonomy, the power to act without depending on others—except, of course, for those you controlled directly. This view of freedom, rooted in independence and property, has profoundly shaped Western concepts of individual rights and liberties.

But when we hold these two views side by side, we can see a tension: one culture saw freedom as rooted in communal support and shared resources, while the other saw it as autonomy secured by ownership. Both are ways of achieving a sense of control and agency, but they reflect different assumptions about what freedom actually requires. If we try to universalize one over the other, we risk ignoring the rich diversity of human experience and values.

Are Human Rights Truly Universal?

David Cigoj’s statement assumes that human rights inherently lead to freedom. But if we look back at the historical roots of human rights in the Western tradition, things aren’t so clear-cut. The idea of human rights is closely linked to the Enlightenment, a period in which philosophers like John Locke argued that all individuals had certain natural rights. Yet, the Enlightenment also enshrined values like property rights and individualism, which are not universally shared across cultures.

In fact, the idea of individual rights often has its roots in systems of hierarchy and control. Roman law, as mentioned, treated property rights as a form of individual freedom, but this also reinforced power structures that allowed some to control others. This raises an important question: are human rights as we understand them today “fruit from a tainted tree”? If they stem from a particular historical context that emphasizes autonomy and ownership, can they really be applied universally?

Indigenous leaders and thinkers have posed this question in different ways. In many Indigenous societies, the emphasis has historically been on collective well-being, not individual autonomy. In this context, rights are not something one asserts against others; they are a shared understanding of responsibilities and mutual support within the community. This is a very different approach, and it’s one that our modern human rights frameworks sometimes struggle to account for.

Freedom as a Balancing Act: Between Autonomy and Interdependence

So, what does all this mean for our understanding of freedom? It suggests that freedom might not be a universal, one-size-fits-all concept. Instead, it may be a balancing act between autonomy—our ability to act independently—and interdependence—the ways we rely on each other and are shaped by our environment. Different societies have emphasised different parts of this spectrum, reflecting their unique histories, values, and challenges.

In today’s interconnected world, maybe freedom requires us to think in both individual and collective terms. We can’t ignore the ways in which our lives are intertwined, whether that’s through social support systems, economic interdependence, or environmental constraints. And we also can’t ignore the ways in which our freedom depends on others’ freedom—after all, no one is truly free if their choices harm or constrain others.

Rethinking Freedom for a New World

Ultimately, the notion that “human rights guarantee freedom” is an appealing but oversimplified statement. True freedom, it seems, is far more complex and context-dependent. It requires us to look beyond individual rights to consider collective responsibilities, historical injustices, and the limitations imposed by our environment.

Perhaps we need to move away from trying to impose one single definition of freedom and instead develop a more nuanced understanding, one that respects different cultural values and acknowledges our interdependence. Freedom might then be seen not as a fixed set of rights but as an evolving practice—one that grows and changes as our understanding of each other, and the world around us, deepens.

In a world facing global challenges like climate change, inequality, and shifting power dynamics, this kind of nuanced freedom—freedom as a practice, not a guarantee—could be what we need most. It might not offer us the simple answers we crave, but it could help us navigate the complexities of living together on a shared planet.

Terry Cooke-Davies

14th November 2024

Profound thanks to ChatGPT(4o) from OpenAI for assistance with this article.