The Deeply Entangled Relationship Between Science and Religion

Seeing Along the Beam vs Looking at the Beam

In an illuminating essay, “Meditation in a Toolshed,” renowned British author C.S. Lewis offers a helpful analogy to consider when exploring the world’s faiths and their relationship with science. Lewis describes two ways of looking at a beam of light in a dark toolshed: either you can look along it, out through a crack above the door of the shed to see the leaves on the trees and the sun itself, or you can look at it, observing the dust particles dancing in the beam of light in the dark interior of the shed.

These two perspectives – looking along the beam and looking at the beam – serve as valuable metaphors for understanding a religion’s internal and external viewpoints. The interior view involves seeing the world from within the framework of the faith and experiencing its teachings, rituals, and spiritual insights as a believer. This is a lived, experiential perspective, often intensely personal, subjective, and filled with nuanced emotions and meanings that are difficult to convey to those outside the faith.

On the other hand, the external view involves examining the religion from an outsider’s perspective, analyzing its doctrines, history, social structures and influences objectively and academically. This is the perspective of the sociologist, the historian, and the scholar of comparative religion – it allows for comparison, critique, and understanding of the religion in its broader societal and historical context.

As we explore the fascinating intersections and dialogues between science and the world’s faiths, we must remember that we primarily look at the beam. We are studying these faiths from the outside, contrasting them with scientific methods and findings. Our perspective fundamentally differs from the internal viewpoint of those who practice and live these faiths, for whom religion may serve as a guiding light illuminating their understanding of the world.

In this examination, we strive for a balanced and respectful exploration that acknowledges the richness, complexity, and diversity of religious beliefs and scientific knowledge. As we proceed, we should remember that every faith, like every scientific theory, offers its unique way of making sense of the universe, and each merits consideration and understanding on its own terms.

Science and Faith: Enemies, Strangers, or Partners?

When considering the relationship between science and faith, philosopher and theologian Ian Barbour offers three broad categories in his influential book “When Science Meets Religion”: Enemies, Strangers, and Partners. These categories provide a helpful framework for understanding science and religion’s complex and multi-faceted interactions.

Enemies: This perspective is often featured prominently in Western public discourse. Historical events like the trial of Galileo Galilei in 1633, the debate in Oxford between Thomas Huxley and Samuel Wilberforce in 1860, and the John Scopes trial in Dayton, Tennessee, in 1925 come readily to mind as evidence of a ‘war’ between science and religion. But as Nicholas Spencer points out in his book, “Magisteria”, “Galileo never said eppur si muove. Huxley didn’t (quite) tell Wilberforce he’d rather be descended from an ape than a bishop. And although Darrow did ask Bryan whether he thought about things he thought about, the Scopes trial was about a good deal more than evolution.” The single coherent story that combines these three unrelated incidents into the familiar “warfare” narrative turns out to be not fact, but a “myth”, first propounded by John William Draper in his 1874 book, “History of the Warfare between Religion and Science”.

In recent years, militant atheists like Richard Dawkins have amplified this sense of hostility. The 2009 advertising campaign on London Transport featuring the slogan “There’s Probably No God. Now Stop Worrying and Enjoy Your Life” is a notable example of this perspective.

Strangers: Proposed by Stephen J. Gould, the concept of “non-overlapping magisteria” suggests that science and religion are entirely separate domains. In this view, science defines the natural world, while religion deals with moral and ethical matters. While this perspective offers a resolution by separating the two domains, it has several challenges. It falters when the domains overlap, such as when religious texts make claims about the natural world. Further complications arise from ethical debates in scientific disciplines and concerns about the reductive nature of science.

Partners: The idea that science and religion can exist as partners is supported by numerous historical examples. The Islamic Golden Age, the concept of God’s two books (nature and scripture) in medieval Christendom, the Deist ideas of the scientific revolution, and Buddhist concepts of mindfulness and meditation in modern psychology all reflect a successful partnership between science and faith.

The work of the psychiatrist and philosopher Iain McGilchrist endorses this perspective from the field of cognitive neuroscience. In his book “The Matter with Things”, he argues that the Western world has lost touch with the sacred and the numinous through an over-reliance on left-brain-dominant thinking at the expense of right-brain faculties that resonate with religious and spiritual experiences.

As we delve deeper into the relationship between science and faith, we must remember that these perspectives are not mutually exclusive. Individuals and communities often navigate a course between these categories, suggesting a dynamic and evolving relationship between science and the world’s faiths.

Science and Faith: Inextricably entangled?

In a highly-acclaimed book published as recently as March 2023, author and scholar Nicholas Spencer not only lays bare the nineteenth-century myth of the “war” between religion and science, he explores the complex relationship between the two domains over more than two millennia and finds it to be inextricably entangled.

In well-written and entertaining prose, Spencer examines the relationship between the three Abrahamic faiths and science, which evolved in parallel into their current entangled relationship. He then describes how the expansive “Western” programme of discovery and colonial expansion that started in the fifteenth century brought scholars and ordinary folk alike into contact with a wide range of “New Worlds”. They encountered a variety of new “religions” which had been hitherto largely unknown.

Indigenous beliefs were dismissed as primitive superstitions, but names were coined for Eastern faiths such as “Buddhism” in 1801, Hindusim in 1829, Taoism in 1838, and Confucianism in 1862. The irony is that these four ancient faiths predate Christianity by at least 400 years and, in many cases, much more.

To the practitioners of these faiths, contact with the expanding “West” brought with it not only science in the form of the technology that conquered their lands and exploited their resources but also an aggressive programme of evangelization.

The following sections will briefly discuss the relation of science first with the Abrahamic faiths and then with the four “Eastern” religions named above.

Science and Christianity: Dynamic Interplay

As observed throughout history, the relationship between Christianity and science has often been complex and multi-faceted, vacillating between adversarial tension and symbiotic partnership.

At various times, Christianity and science have seemed to be “enemies”. For example, during the 4th and 5th centuries, many Christian thinkers expressed distrust towards classical philosophy, viewing it as incompatible with the Christian faith. Similarly, the late medieval period witnessed instances of severe religious backlash against scientific inquiry, notably during the Inquisition, when specific scientific ideas were deemed heretical. The modern “creationism” movement and the emergence of militant atheism, with their rigid ideological standpoints, can also create a sense of conflict between religious and scientific perspectives.

However, there have also been numerous instances when Christianity and science have acted as “partners”. During the Middle Ages, for example, the “Book of Nature” concept reflected a Christian belief that God could be understood through the scriptures and observing the natural world. The 17th century saw the rise of Deism, a philosophical position that advocated for a universe governed by natural laws, suggesting a form of divine craftsmanship compatible with the Scientific Revolution’s discoveries.

In the 20th century, Jesuit support for science produced figures like Georges Lemaître, the Belgian physicist and Roman Catholic priest who proposed the Big Bang theory of the universe’s origin. Today, we can observe a spectrum of views among Christians on science, ranging from “liberal” perspectives that are open to scientific findings and generally perceive science as a “partner” to “fundamentalist” views that are more sceptical of specific scientific claims, perceiving them as “enemies” to faith.

Despite any perceived conflict, it is essential to note that many scientists identify as Christians, seeing no contradiction between their faith and scientific work. This coexistence underscores Christianity and science’s dynamic and diverse relationship, demonstrating the potential for harmony between these two powerful forces in human understanding and experience.

Science and Islam: A Fragile Brilliance

Understanding the historical and present-day relationships between Islam and science requires delving into a rich, complex tapestry of intellectual achievement, theological interpretation, and sociopolitical dynamics. Nicholas Spencer characterizes it as “a fragile brilliance.”

Historically, Islam and science have shared a mutually enriching relationship, most prominently during the Golden Age of Islam, from the 8th to the 13th centuries. During this era, Islamic scholars made substantial contributions to astronomy, medicine, mathematics, and more, building on the foundations of Greek, Indian, and Persian knowledge. They preserved and translated works from Greek and Roman philosophers and scientists, ensuring that this knowledge survived and was further enriched.

Islamic perspectives on science are rooted in the religion’s fundamental teachings. Many Muslims believe in the compatibility of science and the Quran, seeing both as different paths to truth. The principle of tawhid, or the unity of God, is thought to inform an interconnected view of knowledge. All forms of knowledge, including scientific understanding, are considered related and part of the divine unity.

However, the relationship between Islam and science has not been without strain. In recent centuries, science has been associated with Western imperialism, materialism, and consumerism, all of which have influenced Muslim-majority countries through colonial and post-colonial interventions. This has complicated the perception and reception of science in some Muslim communities.

In contemporary Islamic discussions around science, religious scholars, or ‘ulema, often play a crucial role in determining the acceptability of specific scientific practices. This interpretative authority is rooted in the Islamic intellectual tradition, which emphasizes the role of informed scholars in interpreting religious texts and doctrines.

While there are challenges and divergences in views, many Muslims today actively engage in scientific research and contribute to global scientific advancement, maintaining a belief in the essential compatibility between their faith and scientific endeavour. It’s a relationship of “fragile brilliance” characterized by its historical richness, modern complexity, and the potential for future growth and development.

Science and Judaism: Ambiguous and Argumentative

The relationship between science and Judaism is a fascinating interplay and interaction exploration characterized by a deep intellectual curiosity and a profound spiritual quest.

Historically, Jewish scholars played vital roles in Europe and Islamic Spain’s medieval scientific and philosophical traditions. These scholars, like the renowned physician and philosopher Maimonides, contributed substantially to science, medicine, and philosophy. They played a crucial part in translating and preserving Greek and Arabic texts, influencing the course of the Renaissance.

Jewish perspectives on science are deeply influenced by Jewish law (Halakha) and its ability to adapt to changing societal circumstances, including scientific discoveries and technological advancements. The balance between Halakha and scientific inquiry often generates debates that result in progressive interpretations of Jewish law.

Many Jewish thinkers, including contemporary biophysicist Jeremy England, have discussed the compatibility of science and the Torah. Some view science as a means to better understand God’s creation and thus deepen their faith. Notable Jewish philosophers like Martin Buber and Abraham Heschel emphasized the concept of God as the ultimate source of wisdom and knowledge.

A core tenet of Jewish thought lies in the importance of intellectual pursuit and questioning. This ethos aligns well with the scientific method, where inquiry and scepticism are the cornerstones of knowledge acquisition.

In current discussions, Judaism navigates various complex issues such as evolution, creationism, and the universe’s age. Many Jewish scholars seek to reconcile scientific knowledge with the interpretations of the Torah. The implications of scientific advancements are also considered concerning ethical questions, such as those presented by genetic engineering and other biomedical technologies. In these discussions, the balance between embracing scientific progress and upholding Jewish values, such as the sanctity of life, is a central concern.

In this light, the relationship between science and Judaism can be viewed as (in Nicholas Spencer’s phrase) “ambiguous and argumentative”, reflecting a deep commitment to both scientific and also religious understanding. It’s a relationship that is as challenging as it is enriching, constantly pushing the boundaries of knowledge and belief.

Science and Buddhism: Mindful Inquiry

The dialogue between science and Buddhism provides a compelling example of how ancient spiritual traditions and modern scientific inquiry can inspire and enrich one another. This relationship, which we might describe as “Mindful Inquiry”, explores Buddhist practices’ psychological and neurological dimensions, the experiential aspect of Buddhist philosophy, and intriguing parallels between Buddhist thought and modern physics.

Modern psychology and neuroscience have extensively studied Buddhist practices like mindfulness and meditation. The effects on the brain of meditation practices have been well-documented: they can enhance focus, reduce stress, and promote emotional well-being. The Buddhist notion of change aligns closely with neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to rewire itself and form new neural connections, further showcasing the interplay between Buddhist philosophy and neuroscience.

The experiential dimension of Buddhism emphasizes direct experience and introspection. Central to this is meditation, serving as a tool for individuals to explore the nature of the self and reality. Foundational Buddhist teachings, such as the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path, offer practical guides to spiritual growth and understanding.

Furthermore, fascinating parallels exist between Buddhist concepts and modern physics. For example, the Buddhist notions of interdependence and impermanence echo ideas found in quantum mechanics and theories of relativity. With its non-dualistic view of reality, Buddhist philosophy resonates with physicists’ quest to understand the universe’s fundamental nature.

The relationship between Buddhism and science represents a convergence of Eastern and Western thought in exploring reality. This mindful inquiry reflects the mutual enrichment possible when spiritual traditions and scientific pursuits intertwine, ultimately fostering a deeper understanding of ourselves and our universe.

Science, Taoism, and Confucianism: Balanced Interplay

The intersection of science with Taoism and Confucianism offers a unique dialogue that can be termed a “Balanced Interplay.” Despite their distinct foci, both philosophies have contributed significantly to the development of Chinese science and thought, and their influence continues to be relevant.

Taoism is centred around understanding and harmonizing with the natural world. It posits that the universe operates according to the “Dao,” a fundamental and eternal principle that governs all things and events. Pursuing knowledge in Taoism seeks to align with the Dao’s flow, which encourages observation, contemplation, and appreciation of the natural world’s inherent patterns and cycles. This perspective aligns well with scientific enquiry, which strives to discern the laws governing the universe.

Confucianism, on the other hand, emphasizes social order, ethics, and education. It provides a moral and ethical framework that guides human interactions and societal governance. Confucianism champions education and intellectual development for personal cultivation and societal improvement. This focus on learning and knowledge parallels the scientific endeavour’s value for education and informed understanding.

Taoism and Confucianism have shaped a rich tapestry of Chinese scientific thought. Taoism’s commitment to understanding the natural world’s inherent harmony complements Confucianism’s dedication to societal improvement through knowledge. This interplay between the two traditions encourages a balanced and holistic approach to learning, incorporating both the natural and human realms in its scope.

The lasting impact of Taoism and Confucianism is still evident in contemporary discussions about science and philosophy. They offer distinctive perspectives on understanding the natural world and human society, and their teachings continue to provide valuable insights as we grapple with complex scientific and ethical issues today.

Science and Hinduism: A Cosmic Dance

In the interface between science and Hinduism, a unique relationship unfolds that can be described as a “Cosmic Dance.” Hindu concepts of time and space, parallels between Hindu scriptures and modern physics, and the interplay of Hindu ethical principles with scientific advancements highlight this dynamic interaction.

Hindu cosmology presents a multi-layered view of the universe with vast timescales, reflecting a cosmic dance of creation, preservation, and destruction. This is encapsulated in the concept of cyclical time, or Yugas, which parallels scientific theories on the universe’s cyclical expansion and contraction. Hindu cosmological timescales, spanning millions of years, are also strikingly reminiscent of the vast epochs in modern cosmology.

Modern physics also finds intriguing echoes in Hindu scriptures. The concept of Brahman, the ultimate reality that underlies all phenomena, can be likened to the unified field theory in physics, which proposes an underlying field from which all fundamental forces arise. The observer effect in quantum mechanics, where the observer is essential to the phenomenon’s existence, shares commonalities with Hindu perspectives on consciousness and reality.

The principle of interconnectedness, a cornerstone of Hindu thought, aligns with ecological systems thinking in science, recognizing the intricate web of relationships that sustain life.

Moreover, Hinduism provides a rich ethical framework that interfaces with science. The concept of Dharma, or righteousness, serves as a guide for ethical conduct, including in scientific pursuits. Hindu values like non-violence and compassion offer ethical perspectives for addressing global challenges such as climate change, health inequities, and social injustices. The dialogue between Hinduism and science extends to finding a balance between technological advancements and spiritual wisdom in the modern world.

The dance between science and Hinduism reveals a relationship of fascinating interconnections and mutual insights, offering a cosmic perspective that marries the scientific and the spiritual in the quest for understanding reality.

Common Themes Among Religions

Throughout the world’s faith traditions, recurring themes hint at a shared human quest for understanding, purpose, and connectedness. Whether Christianity, Islam, Judaism, Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, or Hinduism, these shared themes weave a common thread through the world’s rich tapestry of religious thought.

Belief in a higher power or powers: Whether monotheistic or polytheistic, most religions posit the existence of divine entities or a universal force that oversees and guides the workings of the universe. This belief often provides a sense of order and meaning to the world.

Morality and ethics: All significant religions offer moral and ethical guidelines for their adherents. These teachings shape individuals’ behaviours and attitudes, providing a sense of right and wrong, good and evil.

Rituals and practices: Rituals are a universal element of religious expression. They provide tangible means to connect with the divine, express devotion, and reaffirm shared beliefs. Practices may include prayer, meditation, fasting, sacraments, and various rites of passage.

Community and fellowship: Religions often foster a sense of community among their followers. Through shared rituals, beliefs, and communal activities, individuals can feel a sense of belonging, mutual support, and collective identity.

Life after death: Most religions contain beliefs about what happens after death. These may include concepts of heaven and hell, reincarnation, or liberation from the cycle of birth and death. These beliefs provide a framework for understanding mortality and give hope for continuing existence.

Personal growth and transformation: Many religions emphasize spiritual growth, self-improvement, and transformation. This might involve practices to develop virtues, attain wisdom, or achieve a closer union with the divine.

The pursuit of ultimate truth or purpose: Religions often orient individuals towards a higher purpose or ultimate truth. This pursuit gives life meaning and direction and encourages individuals to seek more profound understanding and fulfilment.

PERMA and the Shared Themes of World Religions

The work of Martin Seligman and his team at the University of Pennsylvania has significantly shaped the field of positive psychology. Seligman’s PERMA model identifies five elements of well-being: Positive Emotion, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning, and Accomplishment. Intriguingly, these elements resonate strongly with the shared themes found in world religions, illustrating a convergence of psychological science and spiritual wisdom.

Positive Emotion (P): At the core of many religious practices and rituals is cultivating positive emotions. Feelings of joy, gratitude, love, and inner peace are often nurtured through prayer, meditation, and communal worship, reinforcing a sense of well-being.

Engagement (E): Religions provide myriad opportunities for engagement, from participation in communal rituals to the disciplined practice of meditation or ethical precepts. Such engagement can lead to a state of ‘flow’, where individuals lose themselves in the activity at hand, a concept closely aligned with Seligman’s engagement pillar.

Relationships (R): The emphasis on community and fellowship in world religions parallels the Relationships component of the PERMA model. Religions often foster strong interpersonal connections, mutual support, and a sense of belonging, all fundamental to well-being.

Meaning (M): The search for meaning is common to all major faith traditions. Religions propose answers to life’s ultimate questions and provide a framework of purpose and significance that can infuse life with a deep sense of meaning.

Accomplishment (A): Many religions value personal growth, moral development, and spiritual progression. This pursuit of achievement, whether seen as enlightenment in Buddhism, theosis in Christianity, or moksha in Hinduism, mirrors the accomplishment aspect in PERMA.

These parallels between Seligman’s PERMA model and the common themes of world religions suggest that our collective spiritual heritage and contemporary psychological science recognize and affirm the same dimensions of human well-being. This intersection of science and spirituality offers a comprehensive and multi-faceted perspective on what contributes to a fulfilling human life.

Conclusion: The Entangled Relationship of Science with Religion

The relationship between science and religion has often been depicted as binary: conflict or cooperation, dissonance or harmony. However, as we’ve explored in this paper, the relationship is more accurately described as entangled and complex, with elements of tension, harmony, and mutual influence interwoven over time and across cultures.

Science and religion are both born from a fundamental human desire to understand the world around us and our place within it. They represent two different modes of inquiry, one empirical and methodical, the other intuitive and contemplative. They ask different questions and seek answers in different realms of knowledge, but at their best, they complement each other and enrich our collective understanding.

When viewed as ‘enemies’, science and religion appear to challenge each other’s claims and undermine each other’s authority. Historical events such as the trial of Galileo, the Scopes Trial, and ongoing debates about evolution and creationism exemplify this adversarial portrayal.

When seen as ‘strangers’, science and religion operate in separate domains or ‘non-overlapping magisteria’, as Stephen Jay Gould proposed. Science focuses on the ‘how’ questions, exploring the mechanisms and processes of the natural world, while religion deals with the ‘why’ questions, offering moral guidance and spiritual insights.

Yet, as ‘partners’, science and religion can contribute to a holistic view of reality. Historical periods such as the Islamic Golden Age and instances of scientific advances inspired by religious ideas underscore this potential for synergy. Buddhism’s contribution to psychology, the influence of Taoist and Confucian thought on Chinese science, and the resonance between Hindu cosmology and modern physics further illustrate this constructive interplay.

Ultimately, the relationship between science and religion is as diverse and varied as the world’s faith traditions and scientific disciplines themselves. It is influenced by historical, cultural, and personal factors and is subject to change and evolution, much like scientific theories and religious interpretations.

As we continue to explore the frontiers of scientific knowledge and plumb the depths of spiritual wisdom, maintaining a dialogue between science and religion will be essential. Such a dialogue can foster a more nuanced understanding of our world, a greater respect for the mystery and complexity of existence, and a shared commitment to the well-being and flourishing of all life on Earth.

Terry Cooke-Davies

4 June 2023

This article was created with the assistance of an AI language model developed by OpenAI.

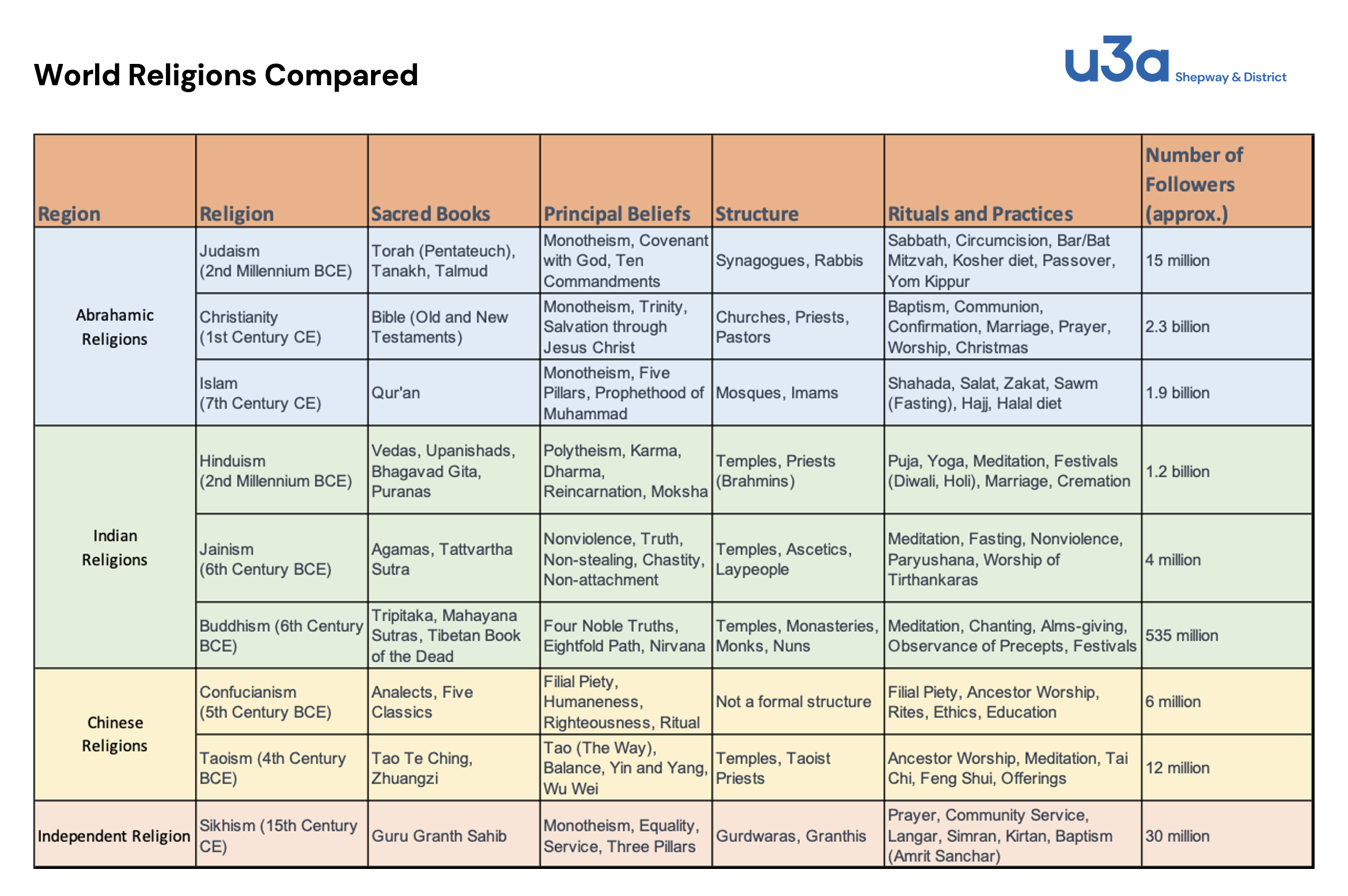

Link to a downloadable version of a table comparing the salient characteristics of nine religions.

Link to a downloadable version of this module’s PowerPoint presentation.