My intellectual lockdown adventure.

Lockdown has been a strange time for many people. My wife and I will have spent a year with significant restrictions on our movements in just over two weeks. Three times, those restrictions have included legal injunctions to ‘stay at home’ for all but essential journeys.

Among other activities, I have had plenty of opportunities to read – to substitute actual physical journeys with voyages of exploration in my imagination. In part, I just wanted to learn more about topics that interest me. But there was more to it than that. A few years ago, shortly after I retired from full-time work, I completed an online programme of study about ‘Positive Psychology’ offered by the University of Pennsylvania. And during that course, I experienced the positive emotional impact of being engaged in an activity that had significant meaning. So perhaps it was natural that I would invest my reading with a purpose beyond straightforward enjoyment.

That purpose was the pursuit of wisdom. Or at least, that was how it seemed to me. For much of my professional life, I engaged in research into how organizations manage projects to bring about strategic change. In parallel with that, as a theologian and, more recently, a lay preacher in the United Reformed Church, I had been engaged in a communal search for spiritual wisdom.

In April 2019, I spent two weeks in Spain, walking the last 270 kilometres of the Camino Frances to Santiago de Compostela. And as I reflected on my experiences during this pilgrimage, mainly my night spent in the village of Samos, I came across the remarkable work of Yale University and the California Institute of Integrated Studies that resulted in the ‘Journey of the Universe’ project.

It was this project, more than anything else, that launched me on my ‘lockdown journey’. In the first few weeks of the journey, two articles that I wrote suggested both a destination (Harnessing Diversity) and a ‘direction of travel’ (The Human Predicament).

But the books that I read, and the sequence in which I read them, seemed to be much more like the yellow arrows painted prominently on roads or buildings along the way towards Santiago than like the neat milestones in Galicia that told you precisely how far you had come, and how far away your destination was. A newspaper column comment might lead me to a newly published book, or a magazine article might summarize recent research. Once immersed in a book, its bibliography might suggest promising titles. It seemed very much a matter of ‘one step leading to the next’.

Pausing to take stock.

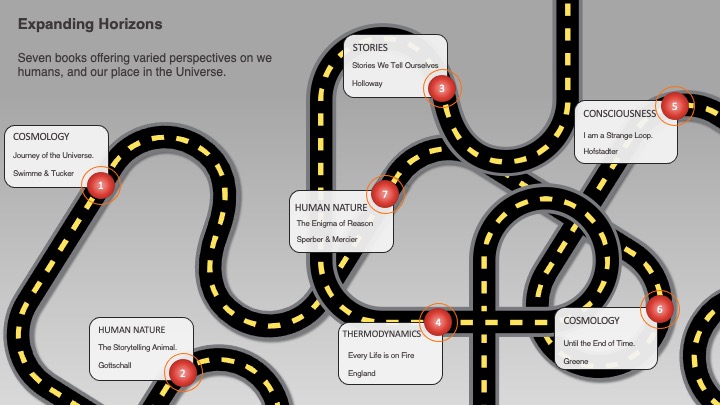

The UK government has now outlined a ‘route to freedom’ from the restrictions, however. And this seems like an appropriate time to pause and take stock of my progress. Six books stand out, although the journey itself feels much more tortuous and winding than the route across Northern Spain.

The diagram above shows the sequence in which I read them, although, for simplicity, it omits many others that I read along the way. So, what did I learn from each of them? And how did that add up to a ‘journey of discovery’?

Journeying with hope

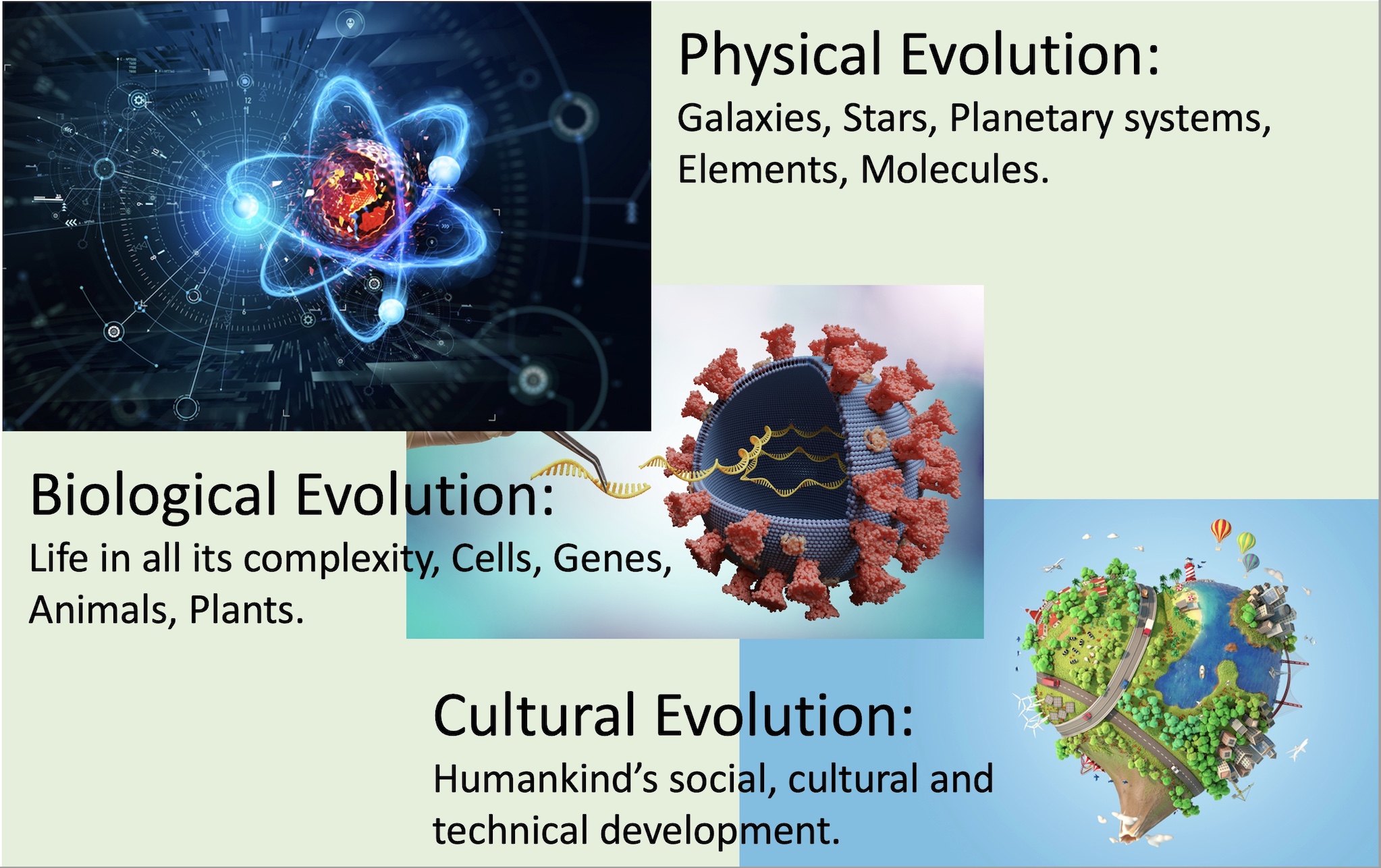

Journey of the Universe’ added two significant strands to my thinking up to that point – both of them involving integration. Firstly, it linked the human search for wisdom through religion and the humanities with humankind’s recent ability to tell a shared ‘origin story’. One that had broad scientific acceptance and could be substantiated at each stage by evidence. And secondly, through telling this origin story as a single ‘big history’, it linked into a single continuum the three hitherto distinct phases of evolution: physical evolution, described in the language of mathematics, physics and chemistry; biological evolution, described in the language of biology, genetics and evolutionary studies; and cultural evolution, described in the wording of the humanities, cognitive science, religion and the social sciences.

Integrating science and theology as two different windows looking into a shared reality appealed to me because of my abiding interest in both worldviews. I found the idea of a continuum of evolution appealing since it centred on the concept of ever-increasing complexity. And I had studied complexity as a part of my academic research into projects and strategic management.

In ‘The Storytelling Animal’, teacher and author John Gottschall argues that stories help humans navigate life’s complex social problems – just as flight simulators prepare pilots for difficult situations. He sees storytelling as an evolutionary trait that has helped to ensure humanity’s survival on earth. By a fortuitous coincidence, while working on an article to integrate these insights into my existing knowledge, a friend who shares my interest in complexity recommended Richard Holloway’s ‘Stories We Tell Ourselves’ to me. It was only a small stretch to incorporate both books into an article entitled ‘The Fascination and Danger of Stories’, that I wrote with an eye on the student of management and the general reader as well as people grappling with the nature of Biblical revelation.

The conclusions fitted well with my prior findings, and I felt increasingly secure in my knowledge. This first part of the journey was stimulating and affirming, with an increasing sense of well-being. The second stage, however, was to prove very different.

Encountering challenging terrain

Many scientists agree with much of the Journey of the Universe’s account of the three phases of evolution, but there is no such emerging consensus on how the thresholds between the stages are bridged. The third and fourth of my six chosen books deal with each of those two thresholds: the emergence of life from inanimate matter and human consciousness from the remainder of the animal kingdom.

Jeremy England, author of ‘Every Life is on Fire’ is unusual in that in addition to being a highly-respected theoretical physicist, he is also an ordained rabbi. From his knowledge of physics in general and thermodynamics in particular, England argues that the answer to the origin of life has been under our noses the whole time, deep within the laws of thermodynamics. He explains how, counterintuitively, the very same forces that tend to tear things apart assembled the first living systems. However, from his life of faith, he also knows how curious we humans are about what it means to be alive. So, in addition to setting out a scientific theory explaining how life began, England applies his approach alongside his scholarly knowledge of the Hebrew Bible to explore humanity’s place in our vast and mysterious universe. I find it particularly interesting that he does so without falling back on any dualistic separation between ‘matter’ and ‘spirit’.

Indeed, it was just as well that I had taken this last point on board before setting out to read Douglas Hofstadter’s mind-bending book, ‘I am a Strange Loop’. Hofstadter, a philosopher, cognitive scientist and mathematician, sets out to answer the question, “Can self, soul, consciousness, “I” arise out of mere matter?” He bases his arguments on recent advances in cognitive science and neuroscience and describes ingenious experiments involving self-referential feedback loops in a closed-circuit television setting. He draws a parallel with Kurt Gödel’s incompleteness theorems by showing that all meaning, derived through layer upon layer of conceptual mental mapping, is ultimately based on analogy.

Hofstadter’s argument is intricate and complex, but I find it powerful. And the combination of this book with England’s has been enough to persuade me that it is at least conceivable that the chain of evolution might bridge the two thresholds without having to believe that ‘spirit’ is a different kind of stuff than matter is. England shows how thermodynamics laws can explain the origins of life from inanimate matter, and Hofstadter shows how Gödel’s incompleteness theorems coupled with the inevitable self-referential nature of consciousness can plausibly explain the evolution of consciousness from non-conscious organisms.

This possibility feels like a massive deal to me. I cannot remember a time when I have not taken it for granted that there is a ‘spiritual’ dimension to life. I had recognized that notions of ‘God’ were impregnated with anthropomorphism. I knew that we inevitable talk about the ineffable in personal terms because of the language we use about feelings, emotions and relationships – all the essential dimensions of our ‘inner lives’. I had even become reconciled to the fact that there is little evidence for the continued existence of such personal experience on the other side of our inevitable death. But for the first time, I find myself having to take seriously the possibility that even our subjective experience of reality may simply be an emergent property of the universe.

Pressing on, fortified with new insights

No sooner had I recognized that this expansion of my horizons was also a shaking of my spiritual foundations, than an old roommate of mine from my University days in the early 1960s suggested that I read a book he was just reading himself. ‘Until the End of Time’ by the eminent physicist, Brian Greene. Another one of those yellow arrows on the path of my journey.

The book’s blurb describes it as a “breathtaking new exploration of the cosmos and our quest to understand it.” In some ways, it is a retelling of the ‘Journey of the Universe’. But whereas Brian Swimme and Mary Evelyn Tucker start out from a background that embraces the spiritual dimension of life, Brian Greene is a self-declared reductionist – comfortable that matter is the only reality in the Universe. It was good to read this after ‘I am a Strange Loop’, because a central feature of both books is the multiplicity of layered concepts that are a feature of human minds.

Greene shows how, as complexity increases and new properties emerge, new layers of concepts and languages are necessary to describe the emergent reality. He refers to them as ‘a series of nested stories that explain distinct but interwoven layers of reality-from the quantum mechanics to consciousness to black holes.’ He makes the point, however, that a switch to a higher-level of language (e.g., biology for living organisms) does not negate the lower-level languages (e.g., chemistry, physics and, ultimately, mathematics). Indeed, for an explanation of reality to be valid at any given level, it must be consistent with descriptions that are proven to be correct at lower levels.

Where the two books diverge is in their central motif. The starting point for ‘Until the End of Time’ is that ‘someday, we know, we will all die. And, we know, so too will the universe itself.’ The subtitle makes it clear that the book is about, “mind, matter, and our search for meaning in an evolving universe.” And after making it clear that the same laws of thermodynamics used by Jeremy England to explain the emergence of life also predict the inevitable ultimate heat death of the Universe, Greene reaches the same conclusion as Richard Holloway that “during our brief moment in the sun, we are tasked with the charge of finding our own meaning.”

Arriving where we started

The final book that I have found myself reading on this exciting but disturbing journey is ‘The Enigma of Reason’ by Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber. I was led to read it by another of those yellow arrows – this time a column in the Times entitled ‘We Need to Discover a New Way of Arguing’ by Iain Martin on 21st February 2021. Although my chosen book was not referred to in the article, it actually provided the research basis and a solid piece of the argument for the book about which Iain Martin wrote. Indeed, I was attracted to the column in the first place because a good deal of my project management research practice had been founded on my experience as a facilitator. Back in May 2020 I had even referred to the same subject in an article entitled ‘We Need Dialogue Not Debate’.

What Mercier and Sperber’s book added to my journey, however, was directly relevant to Greene’s and Holloway’s task of ‘finding our own meaning’. Their proposition is that finding meaning, or reasoning, is not, as commonly assumed, a device that enables us humans to arrive at better beliefs and decisions on our own. On the contrary, it has evolved, complete with all its biases and built-in irrationality, as a device to “help us justify our beliefs and actions to others, convince them through argumentation, and evaluate the justifications and arguments that they address to us. In other words, reason has evolved to help humans better exploit their uniquely rich social environment.”

And so, in a sense, I find myself “back where I started”. Still seeking wisdom. But perhaps, in the words of T. S. Elliott, “knowing the place for the first time”.

Recognizing that any search for wisdom is a shared human undertaking – calling on the collective insights gained among groups of people with very different experiences, and very different sets of assumptions to guide them. And that calls for the very tricky task of debating, arguing, thinking together – call it what you will – in ways that respect the shared search.

Both the need to work together (Harnessing Diversity) and the pressing challenges facing humanity (The Human Predicament) still remain. But I find myself with a renewed enthusiasm for community – not just for social interaction (although that is essential to a social species like humanity), but also for the purpose of finding pathways not just to power and wealth, but to wisdom and to humanity taking the lead in helping the whole earth community to flourish.

Terry Cooke-Davies

St David’s Day, 1st March 2021.