Introduction

For centuries, most Western Europeans believed that God created the world in six days. Adam and Eve were the first humans, created by God on the sixth day. But science has provided us with a radically different story, so that a respected cosmologist can now tell us, “Over the course of 14 billion years, hydrogen gas transformed itself into mountains, butterflies, the music of Bach, and you and me.”

Although science, religion and philosophy have all played their part in the development of this new story, religion and science are often described as two irreconcilable ways of understanding the world. Several well-known historical examples are cited, such as Galileo Galilei’s trial by the Inquisition for supporting the Copernican theory that the Earth revolves around the sun. There is also a regular mention of Darwin’s friend Thomas Huxley and Bishop Samuel Wilberforce’s debate about Darwin’s theory of evolution at the Royal Society in 1860. This confrontation is usually framed as an example of a religion attempting to impede scientific progress. In addition, activist atheists, such as Richard Dawkins, have made the topic prominent in the media over the past thirty or forty years.

Since 9/11 and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, militant Islamicists’ actions have damaged religion’s reputation in the West. Fundamentalist Christian churches and politicians regularly oppose the teaching of evolution in US schools.

However, this depiction of the relationship between religion and science as inevitable conflict is a simplified caricature of a complex relationship shaped by more than just how we interpret the world. Any serious inquiry should additionally consider politics, culture, geography, and philosophy. And that is a huge ask!

This article tackles a “bite-sized” chunk of this humungous topic. It briefly reviews how Christendom has influenced the relationship between science, philosophy and Christianity in Western Europe at different times since the death of Jesus.

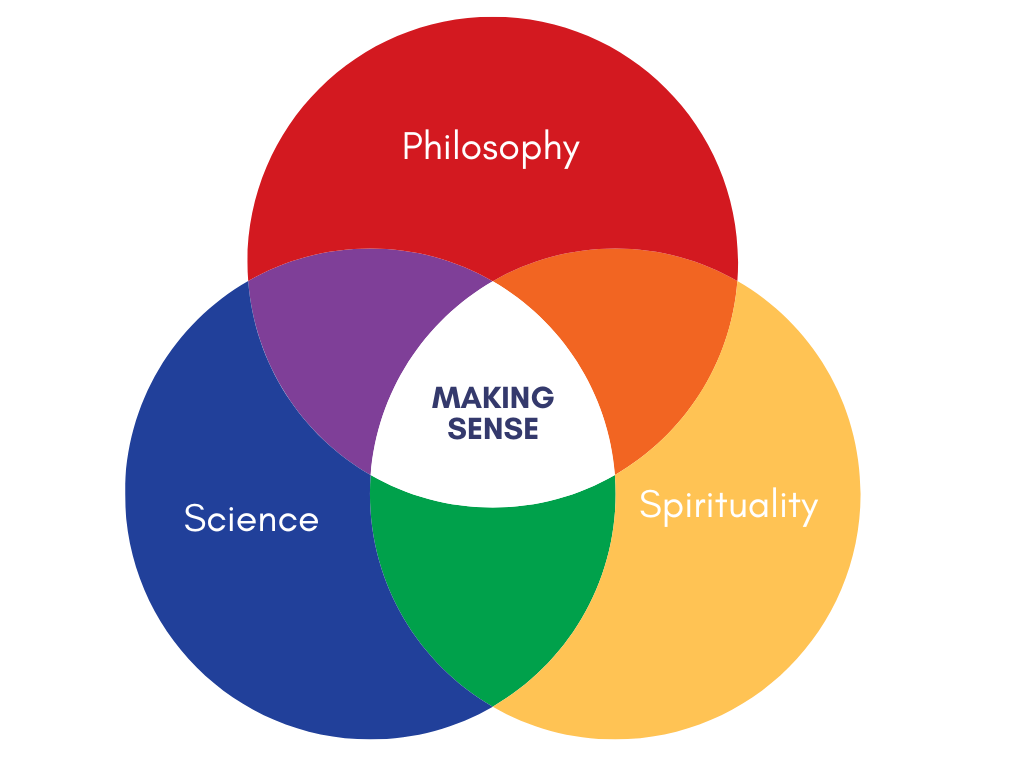

But before we get into that tangled history, we should “clear some ground” by considering how science, religion, and philosophy each in their different ways contribute to our understanding of the world.

Different Ways of Understanding the World

The terms “science” and “religion” are both simplifications and generalisations. There are many sciences, each with its conceptual framework, vocabulary, and community of practitioners. Indeed, there are commonalities between them, but there are also significant differences. Practitioners of geology, neurobiology, and quantum gravity, for example, have very different conceptual models and specialised vocabularies. “Religion” is also a category that includes a wide variety of institutions, activities, and worldviews, from Buddhist monks in Tibet to the Pope in the Vatican.

“Science and Religion” has become a subject of academic study in its own right for the past twenty years. In a lecture recorded on YouTube, Alister McGrath, Professor Emeritus of Science and Religion at Oxford University, distinguishes three different ways of characterising the relationship between the two spheres. The first is “conflict”, which we briefly described in the introduction to this article. The second is “co-existence”, in which the two domains are considered independent fields of study concerned with answering different questions. Science deals with empirical evidence about “how” things function, while religion is concerned with questions of what they mean. The third is “mutual enrichment”, which recognises that there is only one reality. Even though different views of the same reality will appear different, both are valid. This latter relationship calls for constructive dialogue between adherents to the various disciplines, which challenges all parties, partly because each domain offers different ways of understanding the world. Differences in assumptions about what knowledge is, how we acquire it and how we can ensure our beliefs are true (Epistemology). But also differences about what exists and what the nature of reality is (Ontology).

Sciences establish knowledge through gathering empirical knowledge and employing the scientific method. Scientists develop theories that can be tested and potentially disproven through further research. The whole process of science is overseen by a global academic community and through peer-reviewed journals.

Religions generally value ‘faith’ or personal experience obtained through prayer, meditation and life lived in a “community of the faithful”. Their traditions, doctrines, and dogma derive from sacred historical writings, rituals, and practices. Some religions and sects have governing institutions, academic communities, and journals.

Philosophy is different again. A combination of logical reasoning and critical thinking establishes the truth. In addition to formal logic systems, such as mathematics, philosophy is a sister discipline to both sciences and religions since it explains the relationships between different ways of thinking.

So, let us now see how these differences have played out in Western Europe.

The Rise and Fall of Christendom in Western Europe

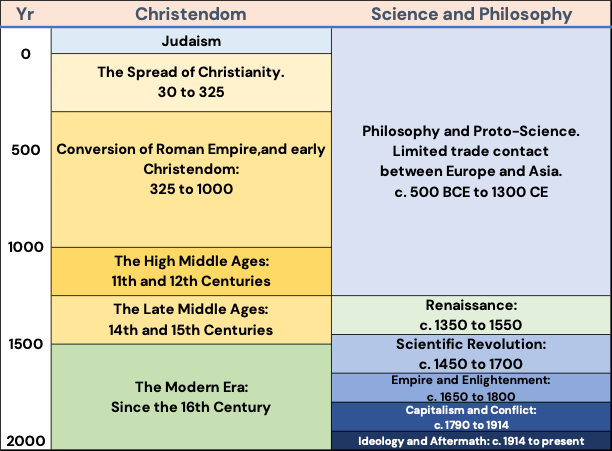

Modern science evolved five hundred years ago, although its roots reach back to much earlier times. Many of its prominent thinkers lived and worked in Western Europe, where Christianity was the dominant religion for almost two millennia. Its combination of political power and cultural impact can be called “Christendom”.

For the sake of brevity, we will divide the period from the birth of Jesus to the present day into five periods: the spread of Christianity, Christianity becoming Christendom, the High Middle Ages, the Late Middle Ages and the Modern Era. In each period, we will highlight a few significant historical events and offer thoughts about the relationship between Christianity and the development of thinking that ultimately led to modern science.

The Spread of Christianity (30 to 325 CE)

Christianity spread rapidly throughout the Roman Empire during the first few centuries of its existence. Partly due to missionaries who travelled throughout the empire to spread the message of Jesus Christ. These missionaries established small communities (known as ‘ecclesia’) in many cities that were the Roman Empire’s commercial hubs.

Selected significant events

- 30 CE: The death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, considered to be the central event in the history of Christianity.

- 50-100 CE: The writing of the New Testament, which contains the teachings of Jesus and the stories of the early Christian movement. It is possible to detect a growing dilution of subversive anti-imperial thinking as the influence of Greek and Roman converts increases.

- 70 CE: The temple’s destruction in Jerusalem marks the Jewish state’s end and the Diaspora’s beginning. It also has implications for Christianity, which increasingly distances itself from its Jewish roots.

- 100-325 CE: Many Roman citizens converted to Christianity, which led to the spread of the religion throughout the Roman Empire.

- 312 CE: The conversion of the Roman Emperor Constantine to Christianity which leads to the official adoption of the religion by the Roman Empire.

Relationship with Greek Philosophy

Greek philosophers were highly influential in laying the foundations for modern science through figures such as Pythagoras (c. 570 to 495 BCE), Plato (c. 427 to 347 BCE) and Aristotle (c. 384 to 322 BCE). Greek thought also influenced the text of the New Testament, which took many Old Testament quotations from the Septuagint – the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible.

However, during the second and third centuries of the common era, there was an attitude of suspicion and scepticism towards Greek philosophy among many early Christians. Some of their leaders saw Greek philosophy as a competing worldview and a potential source of heresy.

However, other prominent Christian thinkers, such as Justin Martyr and Clement of Alexandria, attempted to reconcile Greek philosophy with Christianity. They used elements of Greek thought to explain and defend Christian teachings. These Christian apologists believed that God had influenced Greek philosophy and that it prefigured the truth of Christianity.

Christianity was fragmented, with differing communities adopting diverse attitudes to Greek philosophy.

Christianity Becoming Christendom (325 to 1000 CE)

Constantine’s conversion to Christianity led in 380 CE to the religion’s adoption by the Roman Empire as its official religion. It marked the beginning of Christendom: the period in which Christianity played a central role in Europe’s political, cultural, and social life. Bishops were now officials of the empire, and the institutions of the Church were a component of Roman bureaucracy.

The fall of Rome in 476 CE led to political fragmentation in Western Europe. However, the Eastern Empire, based in Byzantium, continued to flourish. The fragmented kingdoms of Western Europe were gradually reconverted to Christianity under the ecclesiastical leadership of the Pope in Rome.

Selected significant events

- 325 CE: Constantine calls the Council of Nicaea to establish the doctrine of the Christian Church.

- 380 CE: The Edict of Thessalonica declares Christianity to be the Roman Empire’s official religion.

- 476 CE: The fall of the Western Roman Empire, which marks the end of the Roman Empire and the beginning of the Middle Ages.

- 590 CE: The coronation of Pope Gregory I, who is known for his efforts to reform the Church and spread Christianity to the barbarian tribes of Europe.

- 732 CE: The Battle of Tours, in which the Frankish king Charles Martel defeats the Muslim invaders and stops the spread of Islam into Europe.

Relationship with Greek Philosophy and Classical Scholarship

Constantine and his successors were anxious to encourage one single, definitive orthodoxy within the Christian Church, which was the motivation behind the Council of Nicaea. One consequence was an increased effort to purge the Church of all forms of heresy. Physical violence was deployed against those suspected of heresy, encouraged by militant bishops. There is evidence that as a part of this, some groups of Christians targeted works of classical culture to eradicate what they saw as the sinful and idolatrous practices of the pagans. Much of Greek philosophy and the foundation of modern science was lost to Western scholarship by the fall of Rome, coupled with the pagan destruction of much of Roman civilisation in the West.

On the other hand, Augustine of Hippo had an overwhelming influence on Christian theology after the fifth Century. He was deeply influenced by Platonism and found its ideas about the nature of reality and the existence of an immortal soul to be compatible with his own beliefs. He believed that the wisdom of the Greek philosophers was limited and that proper knowledge could only be obtained through revelation from God. He saw philosophy as a helpful tool for understanding and explaining the world but not as a substitute for faith. In his view, the truth of Christianity could not be proven through reason or logic but was instead a matter of personal belief and faith

The High Middle Ages (11th, 12th and 13th Centuries)

During the High Middle Ages, Christendom experienced a period of cultural and economic revival. This was partly due to the growth of trade, the development of universities, and the construction of cathedrals and other great works of architecture.

Selected significant events

- 1054 CE: The Great Schism, in which the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Roman Catholic Church split into two separate churches.

- 1095 CE: The First Crusade, in which Christian armies from Europe attempted to reclaim the Holy Land from the Muslims.

- 1187 CE: The Battle of Hattin, in which the Muslim leader Saladin defeated the Crusaders and re-conquered the Holy Land.

- 1215 CE: The signing of the Magna Carta limited the English king’s power and established the rule of law.

- 1291 CE: The fall of Acre marks the end of the Crusades and the Crusaders’ withdrawal from the Holy Land.

Relationship with Greek Philosophy and Classical Scholarship

Trade with Islamic countries introduced Arabic translations of works by Greek philosophers, which were translated into Latin and made available through monasteries and the newly-founded universities. At the same time, Eastern technology was becoming known through cultural contact along the ‘silk roads’.

Christian scholarship entered what is known as the ‘scholastic’ period, in which Christian doctrine found accommodation with Greek philosophy. Throughout the period, the concept of the “two books” of God, first mentioned as early as the 2nd Century by Justin Martyr, found increasing favour. Thomas Aquinas, the 13th-century Italian philosopher and theologian, wrote extensively about the concept of the “two books” of God. In his “Summa Theologica,” Aquinas developed the idea that God’s “two books” complement each other. He believed that studying nature and science can lead to a deeper understanding of God’s wisdom and goodness and that this understanding can be used to defend the faith.

Aquinas also emphasised that the Bible, as a “book of faith,” and nature, as a “book of reason,” should be read together to gain a deeper understanding of God and the world.

He argued that the ultimate goal of human knowledge is to know God and that studying both the book of nature and the book of scripture is necessary to achieve this goal.

The new universities permitted students to pursue “natural philosophy” alongside theology.

The Late Middle Ages (c. 1300 to 1550 CE)

In the late Middle Ages, Christendom began to decline. This was partly due to the Black Death, which killed millions of people and disrupted trade and commerce, and the rise of secularism, which led people to question the authority of the Church.

Selected significant events

- 1347-1351 CE: The Black Death killed millions and disrupted trade and commerce.

- 1378 CE: The Great Schism, in which the Roman Catholic Church split into two rival factions, leading to the election of two rival popes.

- 1453 CE: The fall of Constantinople marked the end of the Byzantine Empire and the end of the Eastern Roman Empire.

- 1492 CE: The completion of the Reconquista, in which the Christian kingdoms of Spain reclaimed the Iberian Peninsula from the Muslims.

- 1517 CE: The beginning of the Protestant Reformation led to the split of the Roman Catholic Church and the rise of Protestantism.

Relationship with Greek Philosophy and Natural Philosophy

The Renaissance began in 14th Century Italy and was characterised by a renewed interest in classical art, literature, and philosophy, as well as advancements in science, technology, and the arts. The movement spread to other parts of Europe and was marked by a rebirth of learning, an increased focus on individualism, and the development of new ideas about art and politics.

During this period, however, the battle to preserve doctrinal orthodoxy and combat dissent escalated significantly. The Spanish Inquisition was established in 1478 to investigate and suppress heresy, particularly among Jews and Muslims who had converted to Catholicism. Before that, no single institution was known as “the Inquisition”. The Pope had appointed individual agents, frequently from among the Franciscans or Blackfriars. He granted them extraordinary powers to deal with outbreaks of heresy in particular locations.

The Modern Era (Since the 16th Century)

In the modern era, Christendom has continued to decline in influence. Partly because of the rise of secularism and liberal democracy, the development of alternative belief systems, and the increasing diversity of the global population.

Selected significant events

- 1543 CE: Nicolaus Copernicus published “On the Revolution of the Heavenly Spheres”, drawing on the work of Aristarchus of Samos (310 to 230 BC)

- 1620 CE: Sir Francis Bacon published his book “Novum Organum”, which outlined a new approach to scientific inquiry that emphasised the importance of empirical observation and the use of inductive reasoning to arrive at conclusions.

- 1633 CE: The trial of Galileo, in which the Roman Catholic Church convicts the scientist of heresy for his support of heliocentrism.

- 1789 CE: The French Revolution led to the monarchy’s overthrow and the establishment of a secular Republic.

- 1859 CE: The publication of “On the Origin of Species” by Charles Darwin

- 1925 CE: The Scopes “Monkey” trial, in which John T. Scopes was found guilty of violating Tennessee state law by teaching evolution in the classroom.

Relationship with Philosophy and Science

During the past five centuries, the Renaissance gave way to the Enlightenment and an explosion of creativity in all manner of ways. The Protestant Reformation led to a decline in the monolithic power of the Church as an institution and eventually to the structure of Nations in Europe with which we are familiar today. The discovery of New Worlds in the West and Spice Routes in the East brought exposure to utterly different cultures. A chorus of philosophers from Renee Descartes to David Hume and Emanuel Kant questioned traditional modes of thinking and, latterly, the existence of God. The foundations of modern science were laid by scientists like Copernicus, Bacon, Galileo, and Newton, seeking evidence of God’s glory in the regularity and reliability of the “laws of nature”. This so-called “scientific revolution” led to the Industrial Revolution and the rise of liberal democracy.

Change gathered pace, and many apparent conflicts between Christianity and scientific findings involved “changing of the guard” scenarios, in which an old established order wedded to religious traditions has fought a rear guard action to preserve status, power or both.

Concluding Thoughts

This brief review of the rise and fall of Christendom in Western Europe has illustrated the inevitable entanglement of politics, culture, and philosophy with questions about the relationship of religion to science.

In the introduction to this article, we mentioned three different ways of characterising that relationship: conflict, co-existence, and mutual enrichment. My inclination is to the last of these.

In May 2021, I wrote a blog post called “Faith and Science”. It was prompted by an article in “The Times” in which the Archbishop of Canterbury and Lord John Browne, a former CEO of oil giant BP, called for international cooperation to confront not only the pandemic but also the climate emergency. In it, I described how our fundamental human nature makes such cooperation difficult.

But difficult or not, it is increasingly urgent. We need knowledge and wisdom from all sources to minimise the damage we are doing to our planet. Science is widely recognised in public discourse today as the best way of discovering the truth. But we should not allow popular but misguided accounts of conflict between science and religion to dismiss our access to ethical knowledge from the world’s spiritual traditions and philosophy.

Terry Cooke-Davies

January 2023