The Embodied Mind Revolution

Shifting Paradigms – Changing Perspectives

In 1985, the BBC showed a series of ten TV programmes entitled “The Day the Universe Changed”. Presented by James Burke of the “Tomorrow’s World” team, it examined great moments of change in the West, where the fundamental way people thought the Universe works was transformed by new knowledge. The philosopher of science, Thomas Kuhn, describes these foundations of “what we know” as “paradigms” and the moments of change as “paradigm shifts”.

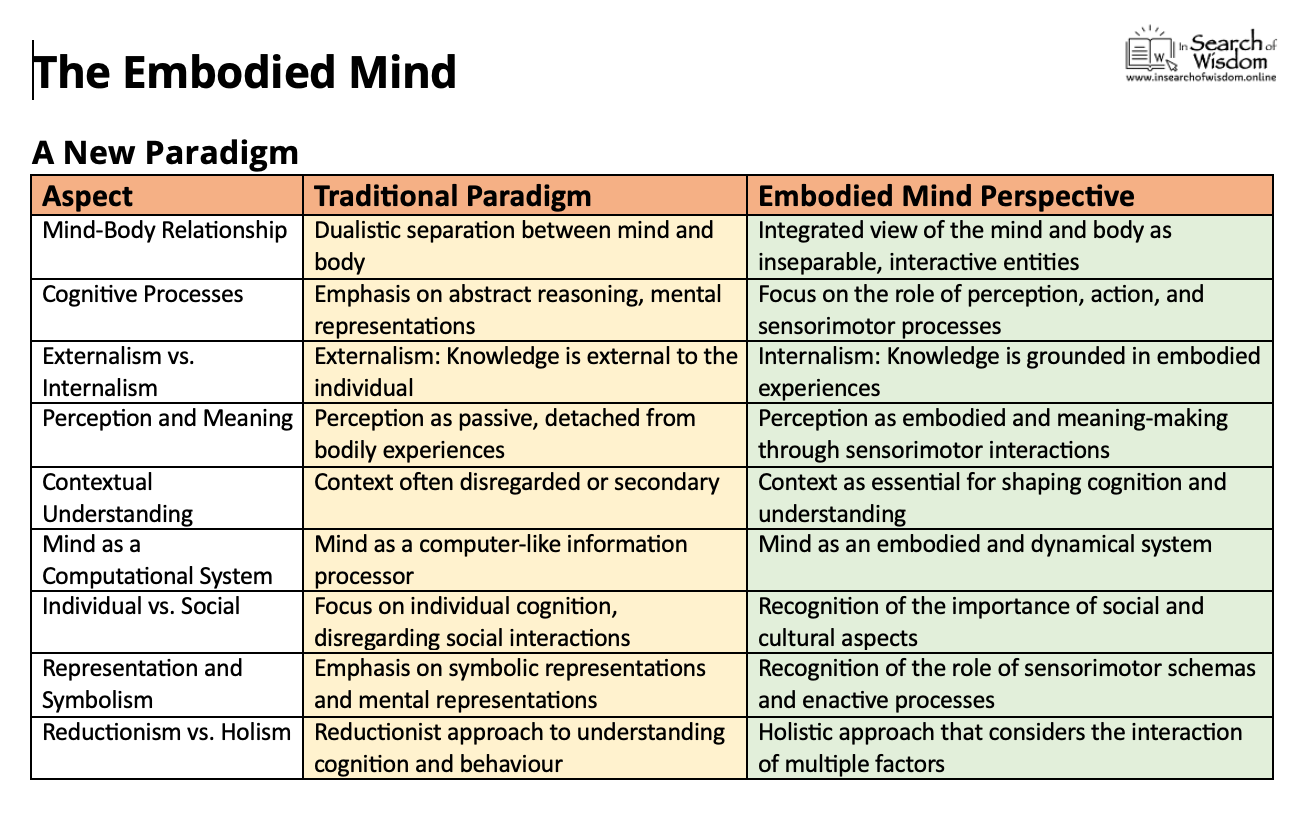

One such change in perspective influences people currently working at the frontiers of cognitive science, psychology, neuroscience, philosophy, linguistics, anthropology, and robotics. It is a change in how we think of the human “mind”, seeing it as an embodied and dynamical system shaped by its context rather than a computer-like information processor. It is often referred to as “the embodied mind”.

In time it will profoundly impact our view of the human condition, our place in the Universe, and our relations with the Earth. But that is not something I could have said even two months ago. I knew of the term ’embodied mind’ from the sub-title of George Lakoff’s and Mark Johnson’s book, “Philosophy in the Flesh”, which made a deep impression on me when I read it twenty or so years ago. But I didn’t discover the extent to which it was changing how we think about what it means to be human until I began to search the academic literature using “embodied mind” as a search term.

I also realized that I had encountered numerous clues throughout my personal and professional life without realizing their full significance. Like the reader of a Hercule Poirot detective story, I had to wait until the great detective (or, in my case, Google Scholar) revealed the whole plot before the significance of each clue became clear.

Four selected clues from my life.

The first clue came from my personal life. In the 1970s and 1980s, I liked to play tennis and squash, although I wasn’t very good at either. The story I told myself was that I was hopeless at ball games, so I made swimming my sport of choice. However, one of my friends recommended me a book by Timothy Gallwey called “The Inner Game of Tennis”. One exercise from it made an enormous difference to my performance on the tennis and squash courts; “try to see precisely how the ball is spinning when it makes contact with your racquet”. When I put this simple instruction into practice, I found that my performance improved dramatically. All right, my wife could still beat me at tennis, but I was no longer ashamed to partner her in doubles, and I managed to climb a couple of leagues at squash.

What had happened was that I had never understood our sports master’s instruction to “keep your eye on the ball”. It hadn’t occurred to me that it meant “right up to the time when you have hit it, caught it, or kicked it.” And once I let my mind keep my eyes occupied with something useful, then my body knew how to play the game much better than my mind did!

The second and third clues came from my professional life, and one led directly to the other. In 2005, as well as running my own project management consulting business, I was a visiting research fellow at University College, London. The Project Management Institute awarded a group of four of us a research grant to study the impact of complexity theory on project management. We chose to do so using a particular theoretical concept developed by Ralph Stacey and his team at the University of Hertfordshire. This concept is known as “complex responsive processes of relating”, which is quite a mouthful. At its core, however, it’s a way of understanding how people interact and form relationships within complex systems like organizations or projects.

Imagine you’re watching a dance. In this dance, every move one dancer makes affects the other dancers. The dance evolves and changes as they respond to each other’s movements. There isn’t a single choreographer directing their every move. Instead, the dance emerges from their ongoing interactions.

Now, apply this image to people in organizations, projects, or communities. Everyone is constantly reacting and adapting to what others are doing. Through these interactions, patterns emerge. These patterns are not planned or directed from above; they naturally arise from countless conversations, decisions, and actions.

But viewing organizations in this way reminds us that:

- People’s minds are interconnected. Just as dancers affect each other’s movements, our actions influence others, and theirs influence us.

- Relationships are dynamic. Relationships and patterns are constantly changing, much like the flow of a dance.

- Outcomes are unpredictable. Since the “dance” isn’t choreographed, you can’t always predict the exact outcome of interactions.

- The pattern emphasizes the importance of the present moment. In this interaction, what happens now matters a lot because it can shape future interactions.

So, if I had known then what I know now, this second clue pointed towards some ideas about how people relate to each other that are central to the new perspective.

One of the outcomes from that piece of research was a series of invitations to each of us to speak at conferences and workshops around the world, and it was at a seminar in Frankfurt that I came across the third clue. The seminar’s theme was complexity in projects; each participant had experience researching some aspect of complexity, projects, or both. Among the twenty invited participants was Professor Gerhard Roth of the University of Bremen Brain Research Institute. He told us about the complex workings of the human brain and introduced us to the idea that the brain has an “energy budget”, which it has to manage for both efficiency and effectiveness. He explained that the brain represents roughly two per cent of body volume but consumes between twenty and sixty per cent of body energy. The cortex is particularly expensive, consuming 75% of total brain energy: 50% for resting activity alone. As a rule, the brain automates as much of its work as possible by relegating it to less energy-consuming sub-conscious parts of the brain.

Had I been more switched on to the whole emerging perspective, these two clues suggested that the mind is formed by interactions with other people and by the experiences and needs of our bodies.

The final clue I want to describe came in July 2022, more than three years after I had retired. My friend and colleague, Dr Mark Winter, invited me to give an online talk to his Manchester University students studying for their Global Executive MBA. We agreed I should cover the topic “Human Nature and Experience”. In preparing the subject, I came across Steven Pinker’s comment in his book, “Rationality” that in recent years, “five Nobel prizes have gone to researchers in cognitive science and behavioural economics who have discovered numerous ways in which people flout the axioms of rational choice.”

That seemed to add weight to Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber’s suggestion that “reason”, far from being the basis of human superiority as “the rational animal”, is a social capability rather than a personal one. As they point out in their book, “The Enigma of Reason”, “When we listen to others, what we want is honest information. When we speak to others, it is often in our interest to mislead them, not necessarily through straightforward lies but by at least distorting, omitting or exaggerating information so as to better influence them in their opinions and in their actions.”

And with this fourth clue, I should have been able to recognize for myself that the mind is embodied (clue 1), embedded in social relationships (clue 2), governed by the brain’s need to manage an energy budget (clue 3), and anything but the rational agent assumed under Western liberal democracy and law (clue 4).

But I couldn’t.

That required me to search the literature for “embodied mind”, and then produce summaries of what recent literature was saying. So what is this ‘embodied mind’ perspective?

The Embodied Mind Perspective

It is the recognition that our cognitive processes, emotions, and behaviours are not solely products of the brain but are deeply intertwined with our bodily experiences and environmental interactions. It asserts that our minds are shaped by sensorimotor activities, sensations, and social contexts in which we are embedded. It draws on a wealth of scientific evidence from disciplines such as neuroscience, cognitive psychology, and embodied cognition research. It is supported by studies exploring the neural correlates of embodied experiences, the influence of sensory-motor processes on cognition, and the role of social interactions in shaping our thoughts and behaviours.

As human beings, we are not surprised by many of these findings. Still, collectively they pose a powerful challenge to the widely held paradigm that has shaped much of our “accepted wisdom” and guided research in many fields during the past few decades.

According to this perspective, long before we can speak or understand language, our brain, locked inside our skull with only sensory input to provide information, forms a model of what is happening both around and inside us. Acting as a control centre for our body, it learns to move our body around and to interact with the world inside and around us, gradually refining the model and simultaneously developing a sense of self. Over time, it learns to manage its energy budget efficiently, keeping much of what it does away from our awareness. As we pay attention to the world around us, and significantly once we acquire language to help us, we interact with people around us, and our model becomes attuned to the social reality of our local culture. It does this by continually modifying our conceptual world in the light of the sensory feedback we receive so that our mind becomes formed by our brains, bodies and interactions with other people and our environment.

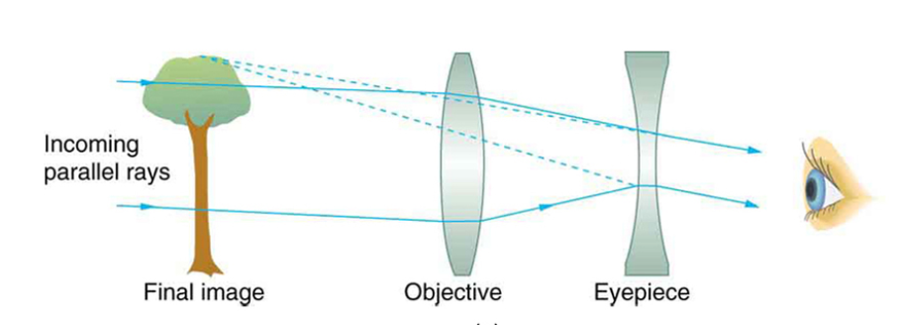

The following example will illustrate just how different this is from the classical Western view of our mind as the rational product of our brain alone, independently of our body. Images like the one below, downloaded from a current exam preparation website, illustrate the act of perception as consisting of light from an external object entering the human eye, where the brain translates it into images, much like a camera does.

If the new perspective is correct, this is a misleading description of what happens. Not because what it says is wrong – but rather because it presents perception as something that originates outside the body and thus underscores the distinction between the mind and an external reality. It sees vision as a means whereby objective information about a “real world out there” enters our brain, where it is received and subjectively processed.

In contrast to this “outside in” description, the embodied mind perspective sees the action starting not with incoming rays of light but with the eye’s attention being focused on the distant object (in this case, the tree). Using its prior experience of what similar patterns of pixels on the retina represent, the mind makes its best guess as to what the object it is attending to might be. If it receives no signals suggesting that the first guess was in error, then it assumes that what it is looking at is the tree it was guessed to be. If we are mistaken, however, and get it wrong the first time, as we receive more sensory input from the eyes or other people talking to us and explaining our mistake (in the form of sensory language input to our ears), we adjust our guess in the light of the error.

Neuroscientist Anil Seth illustrates this using another example from everyday experience with which you might be familiar. Imagine you are out walking in fog, and through the mist, you see the outline of a figure that looks familiar to you. You walk faster to catch up with your supposed friend, but as you get closer and your view clears, you realize you were mistaken and the figure you saw was not your friend, but someone you have never seen before.

In both cases, perception involves paying attention to an object, making a guess about what is being perceived, comparing additional incoming sensory information with the original prediction, and, if necessary, correcting those errors in real time. Perceiving is an active, dynamic process very different from the passive reception of data assumed in the classical description.

But how did this new perspective develop? Was it triggered by the insight or work of a single person like Copernicus or Darwin? Not in this case. It is instead a story of scholars in diverse fields linking their insights with those of people from other disciplines to provide answers to questions that bothered them. In the next section, we’ll consider just a few of them.

A Century in the Making

One foundational idea for the new perspective was developed in the USA about a century ago by several philosophers, most prominently John Dewey (1859-1952), who is often associated with the embodied mind perspective, mainly due to his emphasis on the integration of experience, action, and environment. Dewey’s pragmatic philosophy stressed the inseparable relationship between thought, experience, and action, and he highlighted the significance of embodied and situated cognition. While he did not use the term “embodied mind,” his work laid the groundwork for later developments in this area.

For example, in a talk he gave in 1928 to the New York Academy of Medicine, he said, “The very problem of mind and body suggests division; I do not know of anything so disastrously affected by the habit of division as this particular theme. …

The division in question is so deep-seated that it has affected even our language. We have no word by which to name mind-body in a unified wholeness of operation. For if we said “human life”, few would recognize that it is precisely the unity of mind and body in action to which we were referring. Consequently, when we endeavour to establish this unity in human conduct, we still speak of body and mind and thus unconsciously perpetuate the very division we are striving to deny.

I have used, in passing, the phrases “wholeness of operation” and “unity in action.” What is implied in them gives the key to the discussion. In just the degree in which action and behaviour are made central, the traditional barriers between mind and body break down and dissolve. When we take the standpoint of action, we may still treat some functions as primarily physical and others as primarily mental. Thus, we think of digestion, reproduction and locomotion as conspicuously physical, while thinking, desiring, hoping, loving, and fearing are distinctively mental. Yet if we are wise, we shall not regard the difference as other than one of degree and emphasis.”

Building on these foundations, many other scholars in diverse fields have added their insights to the developing perspective. Some of the more prominent include:

Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908-1961) was a French phenomenological philosopher who emphasized the inseparability of perception and embodiment. His work challenged Cartesian dualism and highlighted that our perception of the world is deeply intertwined with our bodily experiences. His ideas laid the foundation for understanding the body-mind relationship as central to cognition.

Francisco Varela (1946 -2001) was a Chilean biologist, philosopher, cybernetician, and neuroscientist. Along with his colleagues, he introduced the concept of “enaction.” This approach emphasizes that cognition emerges through the dynamic interactions between an organism, its environment, and its bodily actions. Varela’s work contributed to developing embodied cognition theories by focusing on cognition’s active and embodied nature. In 1987, Varela and R. Adam Engle founded the Mind and Life Institute to sponsor a series of dialogues between scientists and the Dalai Lama about the relationship between modern science and Buddhism. Today, it offers grants and services related to personal well-being, compassionate communities and the human-earth connection – three areas connected to its commitment to nurturing individual, societal, and planetary flourishing.

George Lakoff (b 1941) is an American linguist and philosopher who, together with fellow linguist, philosopher and cognitive scientist Mark Johnson (b 1949), has revolutionized linguistic and cognitive theory through their work on “embodied metaphor”. They showed how abstract concepts are grounded in our bodily experiences and metaphoric mappings. Their ideas emphasized that even complex thinking relies on bodily experiences and metaphorical connections.

Andy Clark (b 1957) is a British philosopher and cognitive scientist. His ideas on the “extended mind” proposed that cognitive processes are not limited to the brain but extend into the external environment, including tools and technology. This view challenges traditional notions of cognition and emphasizes the role of our interactions with the world in shaping our mental processes.

Lisa Feldman Barrett (b 1963) is a professor of psychology who specializes in “affective science” (the study of emotions). Her work focuses on the interplay between emotions, the brain, and the body. Her “theory of constructed emotion” challenges the idea of discrete and universal emotions and highlights the role of embodied experiences in shaping emotional states. Her contributions have expanded our understanding of the embodied nature of emotions.

Anil Seth (b 1972) is a Cognitive and Computational Neuroscience professor at the University of Sussex. His research in “predictive processing” has contributed to understanding how our brains generate perceptions and predictions about the world. He emphasizes that the brain constructs perceptions based on predictions and incoming sensory data. His work highlights the active role of the brain in shaping our subjective experiences.

Final Thoughts

In the opening section of this paper, I described how I stumbled across several clues to the existence of a new way of thinking about what it means to be human but didn’t appreciate their significance until the full extent of the “embodied mind” perspective gradually dawned on me. I’m still grappling with the full implications – for me, projects, and the grand challenges we humans currently face.

With the help of ChatGPT Plus, I already wrote one brief article “Exploring the Embodied Mind Paradigm“, but that barely scratches the surface. There is much more to be done, and the paradigm already influences fields such as psychology, neuroscience, linguistics, artificial intelligence, philosophy, education and anthropology.

How long will it take to realize it has significant implications for social topics such as organizational theory, management, politics and law?

Terry Cooke-Davies

20 August 2023

Some sections of this article were created with the assistance of ChatGPT Plus, and the two original illustrations were created using Midjourney, an AI “text to graphics” programme. The image of light falling on the eye was downloaded from 26.5 Telescopes – College Physics (ucf.edu) on 20/8/2023.

Link to Handout

Containing Useful Descriptive Tables

and a Reading List