The Black Death: An Unstoppable Catastrophe

In 1346, Mongol armies laid siege to the Black Sea port of Caffa, a critical hub for trade between East Asia and the Mediterranean. During this assault, the besieging Mongols allegedly unleashed not just military force, but also a deadly biological weapon: the bubonic plague. As infected soldiers died, their corpses were reportedly catapulted into the city as a gruesome tactic, spreading the disease among its inhabitants.

When the siege ended, ships filled with fleeing merchants and soldiers sailed for Italy. However, they carried more than just goods—they were carriers of the Black Death. By the time they arrived in Italian ports, many aboard were already dead. Desperate to avoid the plague, ports tried to turn the ships away, but it was too late. Quite independently of the Siege of Caffa, the disease was already spreading rapidly, following established trade routes, particularly the vast network of Mongol-controlled Silk Roads, devastating cities and towns along the way. Recent genetic analysis of the plague bacterium suggests that the origin may have been in the region of Lake Issyk-Kul in present day Kyrgyzstan.

The Spread and Nature of the Plague (1347-1351)

The Black Death, caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, spread between 1347 and 1351. It was carried by fleas that infested rats, as well as through contact with infected humans. The disease presented in three horrific forms:

- Bubonic Plague: This common form attacked the lymph nodes, causing painful, swollen lumps called “buboes.”

- Pneumonic Plague: This rarer but even more lethal form infected the lungs, and without treatment, it was always fatal.

- Septicemic Plague: The deadliest variant spread through the bloodstream, often killing its victims with alarming speed.

The toll was staggering. It is estimated that between 25% and 60% of Europe’s population perished, while in China, approximately 35% of the population succumbed to the plague.

The Consequences of the Plague

The Mongol Empire, once a vast domain of interconnected khanates and local warlords, had unified regions and intensified cultural and political exchanges across Eurasia. However, these very channels of trade and communication became conduits for deadly germs, magnifying the impact of the pandemic. The demographic collapse was catastrophic—and although other factors came into play, some regions did not fully recover their populations for 200 years.

Interestingly, South Asia did not experience the same level of devastation from the Black Death as Europe, allowing its societies to emerge relatively unscathed. Meanwhile, as the rest of the world grappled with unimaginable loss, new opportunities and “green shoots” began to sprout amid the devastation, setting the stage for profound changes in the societies that survived.

The Islamic Heartland: 1300 to 1500

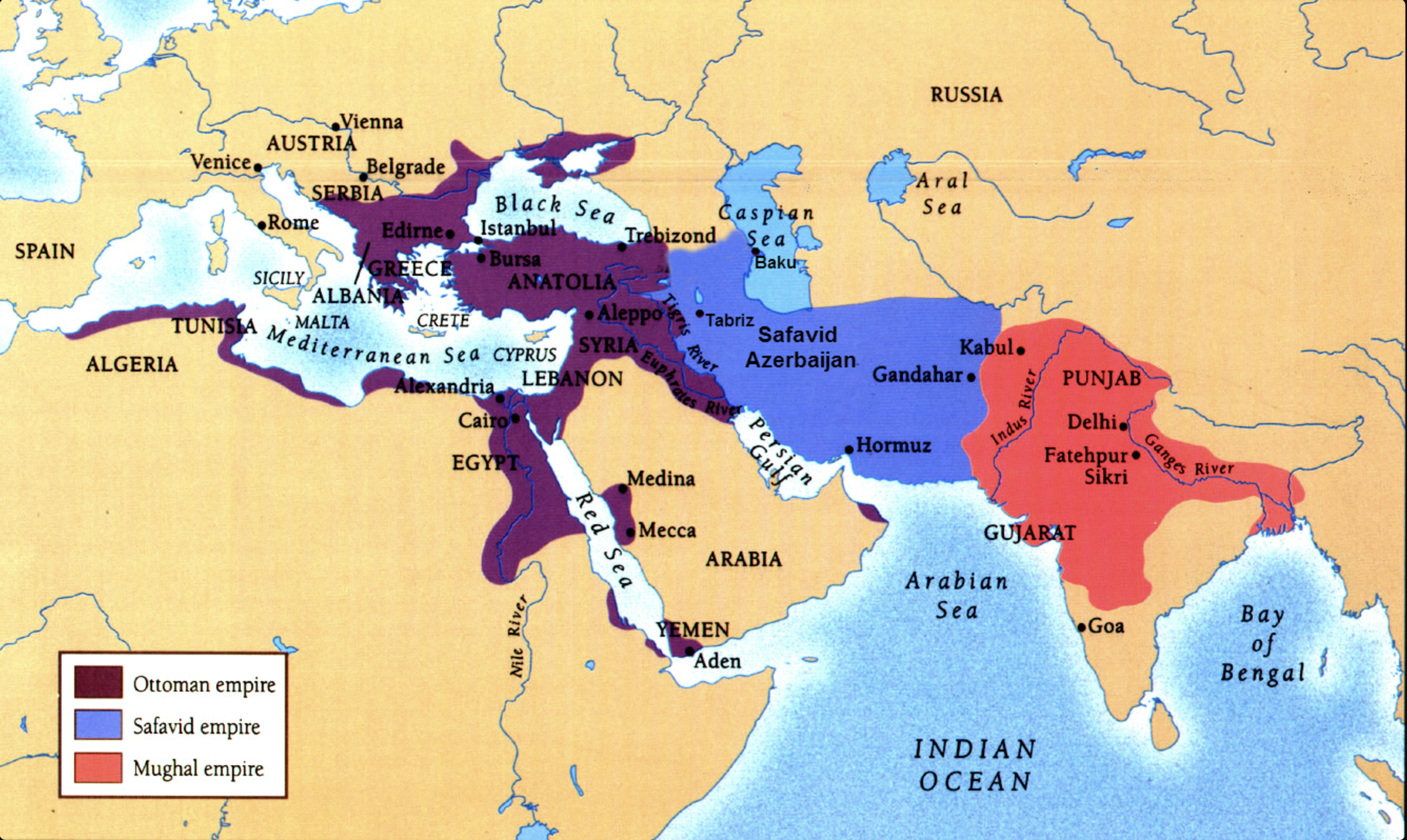

Between 1300 and 1500, the Islamic world was marked by the rise and consolidation of three powerful empires. These empires would not only define the political and cultural landscape of the region for centuries but would also shape the identity of entire nations that exist today. The story of these empires is intertwined with the ambitions of conquerors, the influence of spiritual traditions, and the development of distinct regional identities.

The Ottoman Empire (1299 – 1922)

The Ottoman Empire began as a small Turkic principality in Anatolia under the leadership of Osman I. Amidst the decline of the Mongol Empire, the Ottomans rapidly expanded, capitalizing on regional instability. Their greatest triumph came in 1453 when they captured Constantinople and transformed it into Istanbul, marking the end of the Byzantine Empire.

The Ottomans, predominantly Sunni Muslims, had a notably flexible and pragmatic approach to governance. From time to time they allowed Jews and Christians to integrate within their society, creating a multicultural empire that blended Byzantine, Persian, and Islamic traditions. The architectural marvels of Istanbul—such as the conversion of Hagia Sofia into a mosque and the construction of the grand Topkapi Palace—are legacies of this fusion.

The Ottomans wielded gunpowder weapons and possessed an elite military force, notably the Janissaries, who played a key role in the empire’s military campaigns, leading to the Ottoman dominance that would stretch across three continents.

Timur the Lame (Tamerlane)

Timur, known in the West as Tamerlane, was a real historical figure who inspired legends, including Christopher Marlowe’s play “Tamburlaine the Great” in the 1580s. Born in 1336, Timur was a Turkic-Mongol conqueror who sought to revive the glory of the Mongol Empire. He turned Samarkand into a vibrant centre of Islamic art, science, and architecture, while also building a reputation for extreme violence and conquest.

Timur’s campaigns included weakening the Delhi Sultanate and delivering a rare defeat to the Ottomans at the Battle of Ankara in 1402. Though his empire was short-lived, his conquests set the stage for the emergence of the Safavid and Mughal empires, which would inherit and expand upon his legacy.

Sufism: A Mystical Form of Islam

Sufism, a mystical branch of Islam that emphasizes a direct, personal experience of God, emerged early in Islamic history. Influenced by Christian monasticism, Persian mystical traditions, and other spiritual practices, Sufism became a significant force within the Islamic world.

One key figure was Sheikh Safi al-Din Ardabili (1252-1334), a Sunni Sufi mystic who founded the Safaviya order within Persia. The Safavid dynasty claimed his legacy, transforming Sufism into a political and religious force in the region.

The Safavid Empire (1501 – 1763)

The Safavid Empire, founded by Shah Ismail I, was a powerful Persian dynasty claiming descent from Sheikh Safi al-Din and the Prophet Muhammad. Initially relying on the support of Turkic tribal warriors (the Qizilbash), the Safavids later established a professional standing army to secure their power.

The Safavids were staunch Shia Muslims who made Shia Islam the state religion, enforcing it with considerable zeal, including the persecution of Sunni communities. They also fostered a distinct Persian identity, making Isfahan one of the world’s most beautiful cities. Interestingly, the echoes of the Safavid and Ottoman rivalry could still be heard during the Iran-Iraq War of the late 20th century, as leaders like Saddam Hussein and Ayatollah Khomeini invoked the legacies of these empires to rally their people.

The Mughal Empire (1526 – 1857)

The Mughal Empire was established by Babur, a minor Timurid prince who claimed descent from both Timur and Genghis Khan. After capturing Kabul in 1504, Babur defeated the Delhi Sultanate in 1526, laying the foundation for one of India’s most iconic empires.

Under Akbar the Great (1556 – 1605), the Mughal Empire expanded significantly. Despite being Sunni Muslim rulers, the Mughals presided over a predominantly Hindu population and adopted a policy of religious tolerance. This era saw the flourishing of architecture and art, culminating in masterpieces like the Taj Mahal.

Western Christendom: 1300 to 1500

In contrast to the Islamic world’s and China’s unified empires, Western Christendom in the late medieval period was marked by a fragmented landscape of small, feuding states. Latin was the only common language, understood mainly by educated churchmen and largely inaccessible to the broader population. The decentralized nature of these small states, combined with the devastation of the Black Death, created instability and widespread rebellion, similar to the upheaval seen in post-bubonic Asia.

Church and State: Crisis and Reformation

The authority of the Church, once Europe’s spiritual and cultural anchor, faced serious challenges during this period. The Avignon Papacy (1309 – 1377) saw the seat of the Pope move from Rome to Avignon, leading to the Great Schism (1378 – 1417), during which rival popes claimed legitimacy. This crisis undermined Christendom’s unity and intensified criticisms of church corruption.

The lavish lifestyles of the clergy, the sale of indulgences, and other corrupt practices became focal points for reformers. The survivors of the Black Death, encouraged by their newfound bargaining power, demanded greater freedom, justice, and higher wages. Social unrest spread across Europe, revealing deep cracks in religious and secular authority.

In Spain, the marriage of Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile in 1469 unified two major kingdoms, leading to the final expulsion of Muslim forces from the Iberian Peninsula. Their reign also saw the establishment of the Spanish Inquisition, aimed at enforcing religious conformity. While often remembered for its brutality, the Inquisition introduced legal reforms—such as the appointment of legally trained judges and formalized record-keeping—that contributed to the development of judicial systems still in use today.

The Changing Nature of the European State

By 1500, the governance of England, France, Spain, and Portugal had moved significantly away from the decentralized, feudal structures of 1300. These nations were on the path toward becoming centralized states with more professionalized administrations, standing armies, and a stronger sense of national identity. The shift was part of a broader transformation in Europe that laid the foundations for the modern state system.

A New Flowering of Knowledge

The period from 1300 to 1500 also witnessed a remarkable intellectual revival. In 1440, Johannes Gutenberg invented the movable-type printing press, revolutionizing the spread of information. His most famous work, the Gutenberg Bible (printed around 1450), marked a turning point in the accessibility of knowledge.

Meanwhile, the fall of Constantinople in 1453 to the Ottoman Turks triggered an influx of Greek scholars into Europe, bringing with them precious Latin translations of classical works and Islamic texts. The intellectual heritage of Muslim Spain also flowed into Europe, offering access to advances in Islamic science, mathematics, and philosophy.

This confluence of ideas fuelled the rise of Humanism and the Italian Renaissance, with a renewed focus on human reason, critical inquiry, and a return to original sources. Scholars and artists sought to revive the knowledge of ancient Greece and Rome, paving the way for a period of profound cultural and scientific development.

By the close of this period, the Age of Exploration was beginning to take shape. Prominent monarchies funded expeditions that would reshape the world, led by figures like Christopher Columbus, Ferdinand Magellan, and Vasco da Gama. These voyages marked the dawn of European global expansion, and the beginning of an era defined by exploration, conquest, and trade.

Ming Dynasty China: 1368 – 1644

The Ming Dynasty rose to power in the aftermath of the Mongol-led Yuan Dynasty, which was significantly weakened by the Black Death and internal strife. Economic instability, combined with the devastating effects of the plague, fuelled widespread peasant rebellions. Among these was the Red Turban Movement, a millenarian uprising that ultimately led to the overthrow of the Yuan Dynasty in 1368. Zhu Yuanzhang, a former leader of the rebellion, established the Ming Dynasty as Emperor Hongwu.

Emperor Hongwu’s Reforms

Emperor Hongwu’s reign was marked by significant reforms aimed at stabilizing and revitalizing China. He redistributed land to small farmers, re-established the Confucian civil-service examination system to ensure meritocratic governance, and curbed the power of the eunuchs and the aristocracy. Hongwu emphasized agricultural productivity and sought to restore traditional Chinese culture and values, steering China away from Mongol influences and back to its roots.

The Reign of Emperor Yongle (1402 – 1424)

Yongle, also known as Zhu Din, was a son of Hongwu who overthrew and killed his father to become one of the most prominent Ming emperors. He moved the capital to Beijing and commissioned the construction of the Forbidden City, a grand architectural achievement that symbolized imperial power. Under his leadership, the Great Wall was strengthened and expanded to guard against Mongol incursions, and he launched several military campaigns to secure China’s borders.

Yongle also prioritized maritime trade and diplomacy, expanding China’s influence overseas. His reign saw the commissioning of the famous voyages led by Admiral Zheng He.

Admiral Zheng He’s Voyages (1405 – 1433)

Zheng He’s seven maritime expeditions are legendary for their scale and ambition. Commanding a fleet of over 300 treasure ships, Zheng He sailed across Southeast Asia, India, the Arabian Peninsula, and the East African coast. These voyages were not only a display of China’s power but also an effort to expand the tribute system, establish trade connections, and promote diplomatic relations.

The first three voyages (1405-1411) focused on Southeast Asia and India, while the last four voyages (1413-1433) reached as far as Arabia and East Africa. Despite the grandeur of these expeditions, they were ultimately discontinued after Yongle’s reign, as later emperors turned inward, prioritizing land defence over overseas ventures.

While some controversial claims, popularized by author Gavin Menzies, suggest that Zheng He reached America and Australia or even triggered the Italian Renaissance, these assertions are widely rejected by scholars as lacking credible evidence.

Pestilence and Recovery: A Coherent Narrative

The story of the 14th and 15th centuries is one of devastation and renewal, marked by the cataclysmic spread of the Black Death and the complex processes of recovery that followed. Across diverse regions—Western Christendom, the Islamic world, and Ming China—societies responded in different ways to this shared crisis, ultimately shaping the course of global history.

The Black Death: Catalyst of Change

The Black Death erupted in the mid-14th century, carried along trade routes that linked distant civilizations. Its impact was staggering, wiping out a third of China’s population, decimating towns and cities across Europe, and destabilizing the economies of empires. In China, the weakened Yuan Dynasty crumbled in the face of peasant rebellions, giving rise to the Ming Dynasty. In Western Christendom, the population loss fueled social unrest, emboldening survivors to demand greater freedoms and igniting criticism against the corruption of the Church. The shock of the Black Death created fertile ground for both the collapse of old regimes and the emergence of new ideas.

Resilience and Renewal in the Islamic World

In the Islamic heartland, the period from 1300 to 1500 was one of both fragmentation and consolidation. The Ottoman Empire rose from a small Anatolian principality to a vast, multicultural empire, integrating Byzantine, Persian, and Islamic traditions. Meanwhile, Timur’s conquests—though brutal—laid the groundwork for the Safavid and Mughal empires, which would define the Persian and Indian landscapes for centuries. Amidst this turmoil, Sufism offered spiritual solace and a sense of continuity while also influencing the emerging Safavid state.

The Islamic world’s resilience in the face of instability was not just a matter of political power. The exchange of knowledge—particularly through Islamic science, mathematics, and philosophy—would soon flow into Europe, enriching the intellectual ferment of the Renaissance.

The Dawn of the Renaissance in Western Christendom

In Western Christendom, the post-plague era saw profound shifts. The Avignon Papacy and the Great Schism fractured the Church’s authority but also sowed the seeds for reformist ideas. The rediscovery of Classical texts and the influence of Islamic scholarship converged with technological innovations like the printing press to fuel the Renaissance. Humanism’s focus on critical inquiry and a return to original sources began to reshape European thought, setting the stage for the Reformation and the Scientific Revolution.

The consolidation of state power also gathered pace. In Spain, the unification of Castile and Aragon under Ferdinand and Isabella culminated in the Reconquista and the establishment of the Inquisition. This drive for religious purity contrasted with the more flexible governance seen in the Ottoman Empire, highlighting divergent paths to state-building and control.

Ming China: Recovery and Retrenchment

Ming China offers a different model of recovery. After the trauma of the Black Death and the fall of the Yuan, the Ming Dynasty restored Chinese cultural identity through land reforms, agricultural revitalization, and a return to Confucian values. Under the Yongle Emperor, China briefly looked outward with the grand maritime expeditions of Admiral Zheng He. These voyages showcased China’s might, but were ultimately abandoned as the Ming turned inward, focusing on land defence and internal stability.

China’s decision to retreat from global exploration sharply contrasted with Europe’s Age of Exploration, which was just beginning. While Europe’s maritime powers sought to expand their global reach, China fortified its borders and consolidated its imperial traditions, setting the stage for different trajectories in global history.

The Cycle of Pestilence and Recovery

Across these varied regions, the story is one of pestilence followed by resilience and renewal. Societies shattered by the plague reconfigured themselves—sometimes through conquest, sometimes through intellectual and cultural revival. The legacies of this period are vast: the rise of the Ottoman and Ming empires, the intellectual flowering of the Renaissance, and the new dynamics of trade and power that would shape the early modern world.

The era of “Pestilence and Recovery” illustrates how societies respond to existential threats not merely with survival but with transformation. Whether through the consolidation of state power, the revival of cultural traditions, or the exploration of new frontiers, the aftermath of the Black Death set in motion processes that would define the course of global history for centuries to come.

Terry Cooke-Davies

28th August 2024

With thanks to ChatGPT(4o) for support and co-operation in the preparation of this blog post.

Link to Additional Resources

Click on this link to visit a web page with links to resources used in preparing the u3a session, which this article summarizes.