From the Soil of Athens to the Branches of Western Thought

Introduction

In “The Roots of Western Thought,” we learned that the Greek-speaking city-states of the Eastern Aegean introduced philosophy to the World. Thales, who lived in Miletus, is the first known philosopher from this region. Miletus was a city-state on the coast of Asia Minor. It had negotiated special treaties with the Persian overlords who dominated Western Asia from their centre in Persepolis for most of the sixth century BCE until the Ionian revolt of 499 BCE. This revolt initiated fifty years of wars between Persia and the Greek city-states, led by Athens and Sparta. Finally, the Greeks gained autonomy at the peace of Callias in 449 BCE.

This was followed by a period when the many Greek-speaking city-states evolved from rule by oligarchs (groups of aristocrats sharing government between them) or tyrannies (rule by a single aristocrat who seized sole rule by force) to democracies (which were very different from modern Western representative democracies). However, the precise details of this varied from one city-state to another. It was not an unbroken, continuous trend in one direction only. But one of the driving forces behind this change was military innovation – the citizen armies of heavily armoured ‘hoplites’ with their heavy iron shields and fast, manoeuvrable triremes with their three banks of oars and deadly undersea iron rams.

Reconstructions of a hoplite soldier and triremes.

In the past, the ruling aristocracy was in charge of defending city-states or deciding to go to war with neighbouring states. However, after the introduction of the hoplite, farmers who owned a pair of oxen were required to equip themselves with hoplite armour and weapons and train as a civilian army. This change provided them with greater independence from the aristocracy. In fact, during this period, the word ‘autonomy’ was first coined, reflecting a sense of personal agency that was unknown in other ancient civilizations. In his book, “The Geography of Thought”, Richard Nisbett writes, “Greeks of the classical period, from the sixth to the third century B.C., travelled for long periods under difficult conditions to attend plays and poetry readings at Epidaurus from dawn till dusk for several days in a row. … Among the great civilizations of the day, including Persia, India, and the Middle East, as well as China, it is possible to imagine only the Greeks feeling free enough, being confident enough in their ability to control their own lives, to go on a long journey for the sole purpose of aesthetic enjoyment.”

This was the background, then, to the three giants of classical thought who this article is about: Socrates (469—399 BCE), Plato (424—347 BCE), and Aristotle (384—322 BCE).

Socrates (469—399 BCE)

Socrates’ Background

Socrates came from a modest background. His father, Sophroniscus, was a stonemason or sculptor, and his mother, Phaenarete, was a midwife. This suggests a family of working-class origins, not impoverished but certainly not wealthy. There is little detailed information about Socrates’ personal wealth or income. He served as a hoplite (a citizen-soldier) in the Athenian army, which may have provided some income, but by most accounts, he devoted his life to philosophy without seeking wealth or employment. Socrates is often portrayed as having lived a simple life, eschewing material wealth in favour of intellectual pursuits. His method of philosophy involved public discussions in the agora (public square) of Athens, indicating that he did not charge fees for his teachings.

Socrates is considered one of the fathers of Western philosophy, yet he left no written works. His life and teachings are known primarily through the accounts of his students, notably Plato. Born in Athens, Socrates served as a soldier during the Peloponnesian War and was known for his contribution to the development of critical thinking and ethics. He used a method of inquiry and discussion known as the Socratic method, which involved asking probing questions to challenge assumptions and encourage deeper understanding. Socrates was charged with impiety and corrupting the youth of Athens, leading to his trial and subsequent execution by drinking hemlock. His philosophical legacy emphasizes ethics, the importance of knowledge, and the examination of one’s life.

Socrates’ Main Lines of Thought

Socrates did not write down his thoughts, and most of what we know about him comes from his students, like Plato. Among the main points of his thought are the following:

- Socratic Method: Socrates is famous for his method of questioning, the Socratic Method, aimed at stimulating critical thinking and illuminating ideas. This method involves asking a series of questions to challenge assumptions and reveal underlying beliefs.

- Virtue and Knowledge: Socrates believed that virtue is a kind of knowledge. He thought that if a person knows what is good, they will naturally do what is good. Therefore, to him, all wrongdoing is a result of ignorance, and no one willingly chooses to do wrong.

- The Unexamined Life: One of his most famous quotes is, “The unexamined life is not worth living.” Socrates believed that a life without self-examination and questioning one’s own beliefs and values is not a life fully lived.

- Ethical Living: Socrates placed a strong emphasis on the importance of living a virtuous and ethical life. He argued that living ethically led to happiness and that personal integrity was more important than material wealth or popularity.

- Questioning Conventional Wisdom: Socrates was known for questioning the societal norms and values of Athens. He often engaged with citizens in public places, challenging them to think more deeply about their beliefs and the justifications for those beliefs.

- Socratic Ignorance: Socrates famously claimed that he knew nothing except the fact of his own ignorance. This statement, often summarized as “I know that I know nothing,” reflects his belief in the vast scope of what he did not know, highlighting the importance of humility in the pursuit of knowledge.

- Dialectic Method: His approach to philosophy was dialectical, meaning it was based on dialogue between two or more people who may have different views but wish to pursue knowledge by seeking agreement on universal truths.

- Focus on the Soul: Socrates believed in the immortality of the soul and argued that caring for the soul is more important than focusing on material wealth or physical pleasures. He thought that a well-cared-for soul leads to virtuous living and true happiness.

Some modern practices derived from the Socratic Method

Although the Socratic method was devised and practiced over two millennia ago, it is still widely influential. The following are just two examples:

- Law Schools:

- In modern law schools, the Socratic Method is employed to develop critical thinking and to teach students how to apply legal principles to diverse scenarios. It encourages active participation and continuous engagement with the material.

- Relevance: It mirrors Socrates’ approach by challenging students to analyse, question, and defend their reasoning, preparing them for the complexities of legal practice where they must often navigate ambiguous situations.

- Street Epistemology:

- Street Epistemology is a conversational tool that applies the Socratic Method to engage with people’s beliefs about the world. Its primary goal is to understand and evaluate the justification of belief through a respectful and productive dialogue.

- Relevance: This modern application extends Socrates’ principles beyond academic or legal settings into everyday conversations, emphasizing the importance of critical thinking and reflection on one’s beliefs and values in real-time interactions.

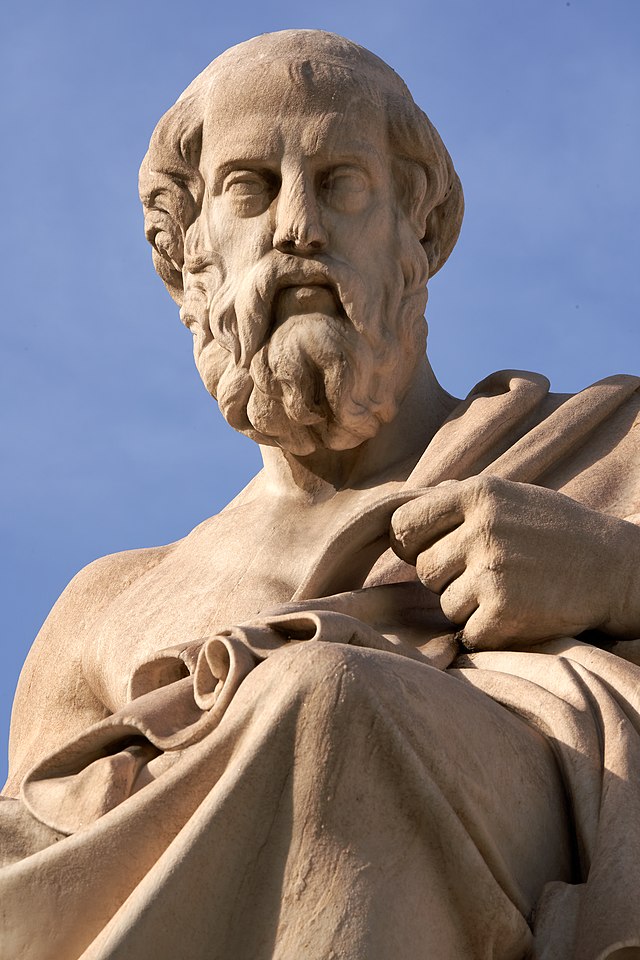

Plato (424 – 347 BCE)

Plato’s Background

Plato was born into a wealthy and aristocratic family. His father, Ariston, was believed to descend from the early kings of Athens, and his mother, Perictione, was related to the 6th-century BCE reformer Solon. This privileged background provided Plato with the means to pursue his interests in philosophy without the need to earn a living in the same way someone of a lower status would. After Socrates’ death, Plato travelled extensively, eventually founding the Academy in Athens. The Academy was one of the first institutions of higher learning in the Western world and likely had the support of wealthy patrons in addition to Plato’s own resources. Plato’s economic status allowed him to concentrate on his philosophical works and the operation of the Academy.

As a student of Socrates, Plato was deeply influenced by his teacher’s fate and devoted his life to continuing Socrates’ work. He founded the Academy in Athens, one of the earliest known organized schools in Western civilization. Plato’s contributions to philosophy are immense, encompassing ethics, metaphysics, epistemology, and political theory. His works are in the form of dialogues, with Socrates often serving as the main character. One of Plato’s most renowned ideas is the Theory of Forms, which suggests that the physical world is a shadow of a more real and unchanging world of forms or ideas. Plato’s Republic is a seminal work in which he explores justice, the ideal state, and the role of the philosopher-king.

Plato’s Main Lines of Thought

Plato made profound contributions across a broad spectrum of philosophical disciplines. His work encompasses ethics, politics, metaphysics, epistemology, and the philosophy of art, among others. Here are some of the main points of Plato’s thought, distilled into key areas:

Theory of Forms

- Plato is renowned for his Theory of Forms (or Ideas), which posits that the material world as perceived through the senses is not the real world, but only a shadow or imitation of the real world. The real world consists of eternal, unchanging forms (or ideas) that represent the essence of various objects and concepts in the material world.

- According to Plato, these forms are the only objects of knowledge that can be truly known, as opposed to the changing physical objects, which can only be believed or opined.

Epistemology

- Plato’s epistemology, or theory of knowledge, is closely linked to his Theory of Forms. He argued that knowledge is a kind of recollection; we are born with knowledge of the forms, and through philosophical inquiry, we can recollect and come to know them.

- In the “Allegory of the Cave” found in “The Republic,” Plato illustrates his view of the ignorant state of most humans and the philosopher’s journey from the darkness of ignorance to the light of knowledge and understanding.

Political Philosophy

- In “The Republic,” Plato outlines his vision of an ideal state, which is ruled by philosopher-kings. He believed that a society should be structured hierarchically, comprising producers, soldiers, and rulers, each class performing its role in harmony with the others.

- Plato’s ideal state is a meritocracy where rulers are selected based on their intellectual capabilities and moral values, not on their wealth or birth.

Ethics

- Plato believed that virtue is a form of knowledge, and that the just life is the most rewarding life for the individual. According to him, the soul consists of three parts: the rational, the spirited, and the appetitive. A just person is one in whose soul these parts are in harmony, with reason ruling over spirit and appetite.

- He also posited that individuals should act in accordance with virtue and that the well-being of the soul is the highest form of good.

Metaphysics

- Plato’s metaphysics is fundamentally tied to his Theory of Forms. He posited that the forms are the most real entities, more real than objects in the physical world, which are mere shadows or reflections of these higher forms.

- He also explored the nature of reality, being, and the world of the forms in his dialogues, using the method of dialectic to uncover truths about the universe.

Philosophy of Art

- Plato had a sceptical view of art and poetry, arguing that they are imitations of the physical world, which is itself an imitation of the world of forms. Therefore, art is twice removed from the truth and can mislead the soul away from the pursuit of the good and the true.

Comparison with Modern Developments

Although Plato’s ‘Theory of Forms’ has been discounted by many modern scientists, a winner of the 2020 Nobel prize for physics sees it as being directly relevant to our understanding of the nature of reality, in contrast to scientific materialism.

- Penrose’s Theory of Platonic Mathematical Forms:

- Roger Penrose, a mathematical physicist, proposes that the fundamental nature of the universe is mathematical, suggesting that mathematical truths (which he equates with Plato’s Forms) exist in a non-physical realm. Penrose’s work in physics, especially concerning the nature of consciousness and the universe, aligns with the Platonic idea that reality is fundamentally abstract and intelligible.

- Relevance: Penrose’s theory updates Plato’s Theory of Forms with the language and concepts of modern mathematics and physics. It posits that understanding the universe’s nature involves accessing these timeless mathematical truths, much like how Plato’s philosopher accesses the Forms.

- Contrast with Scientific Materialism:

- Scientific Materialism posits that only matter is fundamentally real, and all phenomena, including consciousness, can be explained through physical processes and interactions. This view contrasts sharply with Plato’s Theory of Forms, which holds that the ultimate reality is non-physical and immutable.

- Relevance: The contrast highlights a fundamental philosophical debate about the nature of reality: is it grounded in unchanging abstract Forms (or mathematical truths), or is it fully explainable through the physical, ever-changing world?

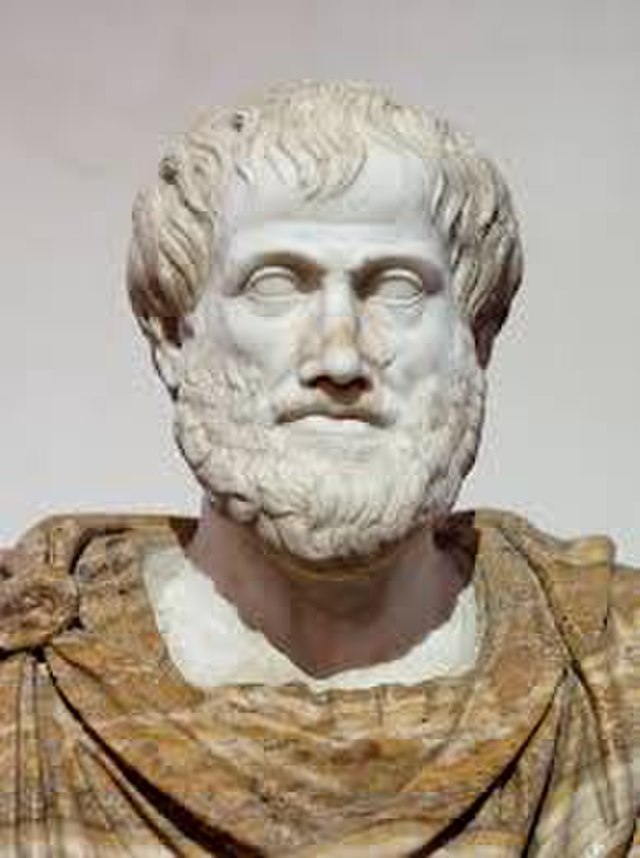

Aristotle (384—322 BCE)

Aristotle’s Background

Aristotle was born in Stagira, a city on the northern coast of ancient Greece. His father, Nicomachus, was the court physician to King Amyntas of Macedon, which suggests a family of considerable social standing, though not necessarily wealthy by the standards of Greek aristocracy. Aristotle’s association with the Macedonian court continued when he was appointed as Alexander the Great’s tutor. After his time in Macedonia, Aristotle returned to Athens and established his own school, the Lyceum. While it is not explicitly detailed, Aristotle’s income likely came from his family’s connections, his work with the Macedonian royal family, and later, possibly, fees from students at the Lyceum. Like Plato, Aristotle’s position allowed him to focus on teaching and writing.

Aristotle was a student of Plato and went on to become a tutor to Alexander the Great. He founded his own school in Athens, the Lyceum, which became a significant institution for philosophical and scientific research. Aristotle’s works cover a wide range of topics including logic, metaphysics, ethics, politics, rhetoric, and biology. Unlike Plato, Aristotle believed that the essence of things could be found in their concrete forms, not in a separate realm of abstracts. His method of logic, especially the syllogism, became foundational to Western scientific and philosophical thought. Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics and Politics are crucial works that explore the nature of virtue, happiness, and the best forms of government. It would hardly be an exaggeration to say that Aristotelian thought dominated Western scholarship for more than 1,400 years, until the Italian Renaissance.

Aristotle’s Main Lines of Thought

Aristotle, diverged significantly from his teacher in many areas, establishing his own comprehensive system of thought that has deeply influenced Western philosophy. Aristotle’s contributions span a wide range of subjects, including metaphysics, ethics, politics, epistemology, logic, biology, and aesthetics. Here are the main points of Aristotle’s thought:

Metaphysics and Ontology

- Aristotle rejected Plato’s Theory of Forms, arguing instead that the essence of things is found within the objects themselves, not in a separate realm of forms. This is known as hylomorphism, the doctrine that substances are composed of both matter (hyle) and form (morphe), which together constitute their essence.

- He introduced the concept of the “four causes” (material, formal, efficient, and final) as a framework for understanding why things exist and how they come to be. The final cause, or purpose, is particularly significant in Aristotle’s explanation of natural phenomena.

Ethics

- In his “Nicomachean Ethics,” Aristotle presents the concept of eudaimonia, often translated as happiness or flourishing, which he considers the highest good for humans. Achieving eudaimonia involves living in accordance with virtue, which is a mean between two extremes of excess and deficiency, relative to us.

- Virtue for Aristotle is a habit or quality that enables individuals to succeed at their function. He distinguishes between moral virtues (formed by habit) and intellectual virtues (arising from instruction).

Politics

- Aristotle viewed the state as a natural institution that emerges from the inherent tendency of humans to form communities. He believed that the purpose of the state is to promote the good life for its citizens, facilitating the attainment of eudaimonia.

- Unlike Plato’s ideal state ruled by philosopher-kings, Aristotle advocated for a constitutional government that best serves the interest of all by balancing the good of the individual and the good of the community.

Epistemology

- Aristotle placed great emphasis on empirical observation and reason as the basis for knowledge. He believed that all knowledge begins with sense experience, from which individuals abstract universal concepts.

- He developed the theory of the “tabula rasa,” arguing that the mind is initially like a blank slate upon which experiences are written, forming the basis of knowledge.

Logic

- Aristotle is considered the father of formal logic, having developed the syllogism as a method of reasoning. He outlined rules for logical argumentation that remained the foundation of logical analysis until the 19th century.

- His work in logic was collected in the “Organon,” where he also discussed the theory of categories, a framework for understanding how different objects, terms, and concepts can be classified.

Natural Sciences

- Aristotle conducted extensive observations of the natural world, which he documented in works on biology, physics, astronomy, and psychology. His approach was empirical and systematic, seeking to classify and explain natural phenomena.

- While many of his scientific theories were later proven incorrect, his methodological approach to science as an empirical endeavour laid important groundwork for future scientific inquiry.

Aesthetics

- In his “Poetics,” Aristotle analyses the elements of tragedy and epic poetry. He defines tragedy as the imitation of an action that is serious, complete, and of a certain magnitude, aiming to evoke pity and fear in the audience, leading to a catharsis of these emotions.

Aristotle’s philosophy is characterized by its systematic approach, empirical basis, and dedication to uncovering the principles underlying the natural world and human society. His work established foundational concepts in logic, ethics, political theory, and science, profoundly influencing the intellectual development of the Western world. Aristotle’s method of inquiry, which combines observation with rational analysis, underscores much of his divergence from Plato and has cemented his legacy as one of the most influential philosophers in history.

The Concept of ‘Phronesis’

Aristotle’s concept of “phronesis,” often translated as “practical wisdom” or “prudence,” is a central idea in his ethical and political philosophy, particularly discussed in his work “Nicomachean Ethics.” Phronesis is one of the intellectual virtues that plays a crucial role in ethical behaviour and moral decision-making. Here are the key aspects of what Aristotle said about phronesis:

Definition and Nature

- Phronesis is an intellectual virtue that involves reasoning and the ability to decide how to act virtuously. It is the capacity to discern the right means to achieve good ends. Unlike theoretical wisdom (sophia), which is concerned with universal truths and the theoretical knowledge of the world, phronesis is about practical matters and how to conduct oneself in the best possible way in the complexities of life.

- It is not merely a skill or technical knowledge (techne) about how to do things, but a deeper understanding that integrates moral insight and the ability to judge what actions are morally right in specific situations.

Role in Virtuous Action

- According to Aristotle, phronesis is essential for virtuous action because it enables individuals to deliberate well about what is good and beneficial for themselves and their community. It involves not just knowing what virtue is, but also how to apply it in the diverse and often challenging circumstances of life.

- A person with phronesis understands why certain actions are virtuous and chooses to act virtuously for the sake of being virtuous. This choice reflects a deep comprehension of the ethical principles that guide life and the practical application of those principles.

Relation to Moral Virtue

- Aristotle posits that phronesis and moral virtue are interdependent: phronesis requires moral virtue, and moral virtue requires phronesis. One cannot be truly morally virtuous without the guiding insight of practical wisdom, and practical wisdom cannot be achieved without moral virtue.

- This interdependence underscores the holistic nature of Aristotle’s ethical system, in which the development of character and the intellect are intertwined. A virtuous person, therefore, is one who possesses both the moral virtues (like courage, temperance, and justice) and the intellectual virtue of phronesis.

Contribution to Eudaimonia

- Phronesis is critical for achieving eudaimonia, the flourishing or well-being that constitutes the highest good for humans. By guiding individuals to make the right decisions and to act in accordance with virtue, phronesis helps individuals live a life that is fulfilling and morally good.

- Through the exercise of phronesis, a person can navigate the complexities of life, making choices that not only adhere to moral principles but also contribute to their own well-being and the well-being of their community.

Education and Development

- Aristotle believed that phronesis is developed through experience and education. It is not an innate quality but is cultivated through practice and the guidance of moral examples. Engaging in ethical reflection and participating in a community with ethical norms are crucial for developing phronesis.

Phronesis, as Aristotle conceptualized it, is fundamental to living a virtuous and fulfilling life. It embodies the wisdom in action that characterizes the ethically mature person, someone who knows the right thing to do and does it for the right reasons, thereby achieving a good and meaningful life.

Comparison with Modern Developments

- Contrast with “Talking Cures“:

- “Talking cures,” a term that broadly encompasses psychotherapeutic approaches, focus on verbal interaction to diagnose and treat psychological distress. While these therapies often aim at behavioral and cognitive changes, they do not explicitly focus on cultivating virtues or leading a eudaimonistic life.

- Relevance: The contrast lies in the methodology and goals. Aristotle’s approach is more prescriptive, emphasising the development of character and moral virtues as the path to well-being, whereas talking cures are often problem-focused and therapeutic, addressing specific psychological issues.

- Comparison with the VIA Institute and Positive Psychology:

- The VIA Institute on Character and Martin Seligman’s Positive Psychology movement emphasize strengths and virtues that enable individuals and communities to thrive. This approach aligns closely with Aristotle’s emphasis on cultivating virtues for a fulfilling life.

- Relevance: Both Aristotle’s ethics and Positive Psychology advocate for the development of moral virtues and strengths as foundational to achieving happiness and well-being. They share a focus on flourishing and the proactive building of a good life through virtuous actions and positive character traits.

Terry Cooke-Davies

February 2024

ChatGPT-4, a generative AI program from OpenAI, produced sections of this text.

Link to Additional Material

Link to a web page containing links to the resources provided in support of this session of the Shepway and District u3a Science, Philosophy, and Wisdom group.